Translating deep thinking into common sense

Do Film Critics Understand Film?

By Vinay Kolhatkar

August 5, 2014

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

1. Introduction

Film is a visual storytelling medium. An objective standard for the analysis of storytelling art is crucial to any rational evaluation of films.

The mind absorbs better when it is emotionally engaged in a story. Stories are like flight simulators, they teach by illustration. Stories that emphasize the efficacy of goal-directed action are consonant with enterprise, free will, and individualism. In a broad sense, stories can be demarcated into ones that promote individualism, or ones that work against it. We denote the former as Romanticism, and the latter as Naturalism. One can also get finer and mark all stories on a continuum instead. The pseudo-intellectual literati promote Naturalism and undermine Romanticism. Most film critics tend to belong either consciously or subconsciously to the pseudo-intellectual literati, or they are lacking an articulated framework, resulting in arbitrary evaluations of art. Film is a visual storytelling medium. An objective standard for the analysis of storytelling art is crucial to any rational evaluation of films.

2. Summary

As a literature movement, Romanticism grew out of the rejection of the idea that fiction writers must embody existing societal norms and ethics in their stories. Writers began to express their own worldview instead. This movement was mischaracterized as having the primacy of emotion.

In The Romantic Manifesto: A Philosophy of Literature, Ayn Rand redefined Romanticism as “a category of art based on the recognition of the principle that man possesses the faculty of volition, and Naturalism, as the category that denies it.” These two diametrically opposed schools, Rand opined, were at the heart of the basic premise underlying all forms of art. Romanticism showcases purposeful action by which men and women try to shape the world around them as against being shaped by it.

Romanticism showcases purposeful action by which men and women try to shape the world around them as against being shaped by it.

In what follows, we will be focusing on the story arts. Other analysts have tended to concentrate their analytical efforts on literature, particularly nineteenth-century literature. However, story art is manifested in various forms—short stories, novellas, novels, graphic novels, advertisements, theatrical plays, comic books, ballads, short film screenplays, and feature film screenplays.

We will be zeroing in on story art as reflected in feature films and television drama, one reason being that this medium has not been analyzed from this perspective to the extent literature has been, and the other being that nowadays, screen stories have a wider reach than books.

In January 1965, Rand wrote the obituary of Romanticism thus—“Partly in reaction against the debasement of values, but mainly in consequence of the general philosophical-cultural disintegration of our time (with its anti-value trend), Romanticism vanished from the movies and never reached television.”

It is now almost half a century later. I wish to present a reality, which, in my opinion, whilst not always celebratory of human efficaciousness, is nevertheless a great deal better than the bleak prognosis Rand gave it in 1965.

Perhaps the reason is that children are often born with a joyous sense of life, and that many adults remain uncorrupted by the pseudo-intellectual literati influence; this is where Hollywood finds a market for Romanticism.

Perhaps there is another reason—one that no one foresaw, which is that Aristotle gives screenwriting teachers a pedigree they otherwise lack.

Aristotle’s Poetics focusses on dramatic theory, not philosophy.

Nevertheless, if you follow its prescriptions as a writer, you cannot but end up with a highly romanticist story; its philosophical foundation is too strong and too well integrated to permit otherwise. In my several years of association with this craft, I never heard a teacher, practicing professional, or an author of a how-to book ever recommend Naturalism.

Aristotle has been liberally quoted in what I have read in books or heard in lectures. In fact, the how-to prescriptions are de facto highly romanticist, notwithstanding that many who teach or write how-to books have either not encountered the term, or have not given it the meaning that Rand did.

Yet, many story outcomes are not so joyously romanticist. One reason is that prescriptions, taken as gospel by those new to the craft, are frequently discarded by the studios and the professionals. Furthermore, film critics, mired in their own pseudo-intellectualism, reward Naturalism, and some of the big awards (like the BAFTAs and the Academy Awards) translate to box-office success for the movie and critical acclaim for the cast and the producer-director-screenwriter team.

Nevertheless, the Aristotle idolization is itself a cause for joy for it opens a door to preserving Romanticism. Even more celebratory are the romanticist stories that do make it to the screen.

It does not behoove us as objectivists to copycat a prognosis fifty years on and proceed to lament the state of the world. We must call it as we see it—nothing less will do. In fact, if the ex post finding that Rand was overly pessimistic in her prognosis is correct, far from turning in her grave, she would actually be delighted.

Notes:

a. I am using ‘Hollywood’ as a metonym to cover all screen stories, including those produced in languages other than English, and including those produced outside the United States.

b. In this context, we will use Rand’s definition of art with an explanatory twist—“Art is an artist’s selective re-creation of reality according to the way an artist sees the world around him—in-principle knowable and conquerable (the romanticist axis), or in-principle unfathomable and unconquerable (the naturalist axis).”

3. Romanticism versus Naturalism in the story arts

If the writer believes that a human being possesses free will, the writer would show him choosing values, and acting to gain or keep them by way of purposeful action, i.e. determining his own fate, or at least seeking strongly to influence it. If, in the writer’s judgment, the world is deterministic or indeterminable, events would unfold in a random way, and the story characters would receive their fate without being able to influence it. Based on this primary distinction, we can derive characteristics of romanticist stories and contrast them with naturalist ones.

The rest of what is Romanticism follows from the imperatives of drama. It is more engaging to watch a strong conflict as against when values are easily achieved through influencing events. It is more engaging to watch a conflict escalate to a final do-or-die battle—e.g. in sports, if the biggest battle took place earlier, how many in the audience would sit through the undercard afterward? The story must have a central issue at stake, which is to be resolved by the final battle, otherwise there is no point in the telling; we can watch average life without going to the movies. Naturalism, on the other hand, focusses on making art uninspiring.

Naturalism, on the other hand, focusses on making art uninspiring

The idea is to show the run-of-the-mill life, the average rather than ‘as it could be at its best’. Such a story would have three or more of these eight characteristics:

a. Having conflicts unresolved at the end, thus subliminally implying that resolution is not likely in real life;

b. Having accidental events determine the fate of the key characters as if accidental events are the key to outcomes;

c. Letting coincidences occur to assist a protagonist’s victory as if one must rely on coincidences to secure victory;

d. Letting all major characters be equally flawed without the flaws being corrected as if moral ambiguity is intrinsic to human nature and self-improvement impossible;

e. Trivializing great achievement by character caricature and stereotyping, implying that great achievers (e.g. inventors) are necessarily eccentric, socially inept, or unhappy;

f. Portraying the as is life in a specific location without a context for a universal truth about humankind to be gleaned from its happenings;

g. The deliberate absence of a clear moral right and wrong (a world full of moral grey); and

h. A meandering storyline that shows ‘a slice of real life’; the art of navel-gazing without a unifying purpose.

Naturalism is an inferior form of art.

Unresolved major conflicts used to be considered inexcusable for a story. Imagine a completed murder mystery, highly imaginative, with multiple viable suspects, that inexorably propels toward a climax, only for the audience to be told at the end that some mysteries remain unsolved; ‘such is life’. If the writer has not figured it out himself, he is cheating his readers by subjecting them to a half-baked idea. It is lazy writing. Naturalism is essentially lazy writing, lazy in the sense that the writer is unwilling or unable to undertake the large amount of thinking that is necessary to write a fully integrated plot and express it well. Naturalism is an inferior form of art.

4. Illustrations of Naturalism on screen

Romanticism is better understood by a contrast with the more severe examples of Naturalism. The following are all 21st Century examples of Naturalism and of lazy writing.

I. Disgrace (2009): JM Coetzee published the novel Disgrace in 1999. It was adapted for a film starring John Malkovich in 2009. The novel won the Man Booker Prize for literature; J.M. Coetzee was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 2003. In the story, David Lurie, a disillusioned (readers are never told why he is so), 52-year-old, white, South African professor of literature in Cape Town, throws away his whole career after he has an affair with a female student. He gives the student a passing grade for an exam she did not take. However, he is indicted for the consensual sex instead, and inexplicably offers no defense even when the way back into his career is clear. He then joins his lesbian daughter Lucy on a farm in the Eastern Cape, where she lives alone, growing flowers and vegetables, for sale at the local farmers’ market. There, the two are subjected to a brutal attack at the hands of three black men; Lucy is gang-raped and beaten; Lurie is set on fire; both survive the attack. Lucy decides to keep the child that she conceives as a result, and to stay on the farm despite the danger—handing over her land to her neighbor and former farmhand, Petrus, who is implicated in the attack in the scenes that follow.

I. Disgrace (2009): JM Coetzee published the novel Disgrace in 1999. It was adapted for a film starring John Malkovich in 2009. The novel won the Man Booker Prize for literature; J.M. Coetzee was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 2003. In the story, David Lurie, a disillusioned (readers are never told why he is so), 52-year-old, white, South African professor of literature in Cape Town, throws away his whole career after he has an affair with a female student. He gives the student a passing grade for an exam she did not take. However, he is indicted for the consensual sex instead, and inexplicably offers no defense even when the way back into his career is clear. He then joins his lesbian daughter Lucy on a farm in the Eastern Cape, where she lives alone, growing flowers and vegetables, for sale at the local farmers’ market. There, the two are subjected to a brutal attack at the hands of three black men; Lucy is gang-raped and beaten; Lurie is set on fire; both survive the attack. Lucy decides to keep the child that she conceives as a result, and to stay on the farm despite the danger—handing over her land to her neighbor and former farmhand, Petrus, who is implicated in the attack in the scenes that follow.

Petrus’ guilt is left to the readers’ imagination—either the attack is a random event or he orchestrates it; readers never find out. Lucy regards her rape as Mother Earth’s revenge for white people domination of black people for a few generations earlier. Lurie, struggling to find a new meaning in his life, fails to write an opera about Byron he otherwise badly wanted to, and instead, devotes his time initially to helping Petrus on the farm, then to euthanizing unwanted dogs at a local animal welfare clinic. At the clinic one day, he suddenly has unsatisfying sex with the aging, unattractive, married, female manager. Finally, upon finding that corpses of unwanted dogs are hammered with a shovel to fit an incinerator entry point, he decides to spend his time meticulously rearranging the corpses to avoid the shoveling, which action, we are asked to infer, gives his life the meaning and himself the dignity that his literature professorship could not.

II. Crash (2004): Using an enormous ensemble cast, with no singularly visible protagonist, and no definitively pursued desires against an ascending conflict, the story liberally uses repetitive coincidence as a plot device to demonstrate that victims of racism are often racist themselves in different contexts and situations in a world full of moral grey. Critically acclaimed, Crash won two Academy awards (including Best Picture) and two BAFTAs (including Best Screenplay).

II. Crash (2004): Using an enormous ensemble cast, with no singularly visible protagonist, and no definitively pursued desires against an ascending conflict, the story liberally uses repetitive coincidence as a plot device to demonstrate that victims of racism are often racist themselves in different contexts and situations in a world full of moral grey. Critically acclaimed, Crash won two Academy awards (including Best Picture) and two BAFTAs (including Best Screenplay).

III. No Country for Old Men (2007): The Coen Brothers adapted a novel involving the story of an ordinary man who stumbles upon a gang-killing scene, and a bagful of money. A cat-and-mouse drama unfolds between a nihilistic psychopathic killer who is chasing the bag of money, and the protagonist, the ordinary man, who turns into an ordinary thief. The psychopath is being pursued by the town’s Sheriff. The psychopath then murders the protagonist, which act the audience has to infer, as the murder, astonishingly, is not shown on screen.

Then more killings occur, as the psychopathic killer decides the fate of his victims by a coin toss. As the killer is trying to get away, coincidentally he is involved in a car accident, which is the other driver’s fault. Nevertheless, he limps away, leaving an unresolved mystery for the aging Sheriff, who, at the end, gives up, effectively acknowledging that there is no order in this universe, the pursuit of justice is futile, and nihilism wins anyway, so it is time for him to quit and wait for his own death. This ties the last scene to the first one—a dream in which he saw his dead father, abruptly switching a thriller to a coming-of-age story. Critically acclaimed, as naturalist stories that celebrate nihilism often are, the film won two Golden Globes (including Best Screenplay), three Academy awards (including Best Picture), and three BAFTAs.

IV. There Will be Blood (2007): A meandering, plot-less story of an oil prospector, initially shown as an entrepreneurial spirit, cognizant of his own strengths, and compassionate to boot, adopting the son of a colleague who suffered a fatal accident. Over time, the prospector morphs into an evil and highly eccentric person, without reason. This violates a cardinal storytelling rule from the Poetics (“Keep your characters consistent over the length of the story”). Tormented (as if any pursuit of wealth must lead to torment), he then disowns his adopted son, and eventually turns into a cold-blooded killer. This movie got into some critics’ Best film of the decade lists, winning two Academy awards, a BAFTA, and a Golden Globe, plus the Academy nomination for Best Picture.

IV. There Will be Blood (2007): A meandering, plot-less story of an oil prospector, initially shown as an entrepreneurial spirit, cognizant of his own strengths, and compassionate to boot, adopting the son of a colleague who suffered a fatal accident. Over time, the prospector morphs into an evil and highly eccentric person, without reason. This violates a cardinal storytelling rule from the Poetics (“Keep your characters consistent over the length of the story”). Tormented (as if any pursuit of wealth must lead to torment), he then disowns his adopted son, and eventually turns into a cold-blooded killer. This movie got into some critics’ Best film of the decade lists, winning two Academy awards, a BAFTA, and a Golden Globe, plus the Academy nomination for Best Picture.

V. The Hurt Locker (2009): One of the most plot-less stories ever to hit the screen, this is a journalistic slice-of-life account of unconnected incidents that happen to occur to a bomb explosives expert. At the end, he confesses to his infant son that the risky excitement of war is the only thing he truly loves. This documentary-style film won six Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Screenplay, and Best Director, and substantive critical acclaim.

V. The Hurt Locker (2009): One of the most plot-less stories ever to hit the screen, this is a journalistic slice-of-life account of unconnected incidents that happen to occur to a bomb explosives expert. At the end, he confesses to his infant son that the risky excitement of war is the only thing he truly loves. This documentary-style film won six Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Screenplay, and Best Director, and substantive critical acclaim.

Notwithstanding the fawning of the critics and the award-givers, Naturalism does also have a fan base, and therefore at times a hard-to-ignore box-office performance. Yet, contemporary screenwriting teaching and its theory applauds Romanticism, virtually without exception.

5. Romanticism clarified

There is no generally accepted definition of Romanticism. Nineteenth century attempts to define it tended to declare it as the primacy of emotions, which definition has persisted to this day. We use Rand’s definition of the primacy of values, essentially of self-selected values, of individualism, and of free will, as a rebellion of the time against the authoritarian dictates of the classical movement. For a fuller exposition of this, refer Walter Donway’s talk on Romanticism at The Atlas Summit 2013.

6. Screenwriting theory and Aristotle

Although there is no one single, unifying body of thought generally accepted as ‘screenwriting theory’ the way Newtonian physics would be for the undergraduate student of physics, there are considerable commonalities in the teachings of screenwriting courses, how-to books, and in the pronouncements of its popular educators.

Screenwriting prescriptions as gleaned from the teachings of its most successful advocates—Robert McKee, the late Blake Snyder, Michael Hauge, Linda Seger, Linda Cowgill, Karel Segers, Syd Field, and Hal Croasmun, are essentially highly romanticist. At first glance, this may not appear to be the case, as some written pieces may ask for a focus on character rather than plot. Yet, the universal recommendation is to have active protagonists who want something badly, to have causality rather than coincidences, internally consistent reality, high stakes, increasing jeopardy, a protagonist propelled into action by self-belief, high-level conflict, a pursuit of objectives/ values, and a climax that results in closure.

Hague, for instance, says, “There must be a clear, specific, visible motivation or objective which the hero hopes to achieve by the end of the story. You can’t just have your hero shuffle through life and call that a movie.” Field cautions—”A screenplay without structure has no storyline; it wanders around, searching for itself, is dull and boring. It doesn’t work.” Cowgill states, “Your protagonist must be committed to something—her goal, a value system, a person, etc.—and be willing to fight for it, even die”. Seger goes further, “We want the protagonist to win, to reach the goal, to achieve the dream”.

Like Rand, screenwriting guru Robert McKee also deplores the loss of story—the loss of what he calls the archplot. In an archplot, there is a single, active protagonist, linear time, a struggle against forces of antagonism to pursue desire, to a closed ending of absolute and irreversible change. McKee then uses the term minimalism to express the minimizing of such values, including devices such as open endings (e.g. Ides of March (2011), No Country for Old Men). Finally, McKee uses the term antiplot to denote a ridicule of formal principles—“the cinema counterpart of the Theatre of the Absurd”, e.g. Monty Python (1971-1983) movies, and Arbitrage (2012) starring Richard Gere.

Aristotle is widely quoted by the screenwriting teacher fraternity. Some have even claimed that everything that is taught today (not just the foundations), was already covered by Aristotle. Aristotle’s Poetics has had several English translations, both literal and interpretive. The interpretive translations tend to be liberally interpretive, i.e. tend to attribute the author’s own agenda or edicts to Aristotle, in order to gain more credence.

A screenwriting theorist (Lanouette, 2012) has recently argued that, “In the ever-expanding family of Arts and Letters conceived by humankind, Screenwriting is one of the newest members. Cursed as the bastard child of Playwriting, she strives for the acceptance of her adoptive father Film, who neglects poor Screenwriting to shamelessly favor his natural daughters Image and Montage.This unfortunate circumstance may explain why it is that Cinderella Screenwriting clings so desperately to a remote ancestry, so quick to remind those who’ll listen that she is actually a direct descendant of the great Aristotle, revered and infallible patriarch of the ancient family of Drama. She rarely misses an opportunity to refer to Aristotle’s Poetics, her pedigree papers, often quoting liberally from it.”

Notwithstanding the likelihood of over-attribution however, there is no denying that Aristotle was prescribing what was later termed Romanticism by Rand. This then begs the question, “If the prescription for Romanticism is universal in the screenwriting community, why are naturalist plots even made into films? Why do they win awards?”

The film-medium educators have no answer to this question. Indeed, many do not understand the nature of this question; some have never considered it. In fact, the act of rationalization is so widespread that educators take award-winning films and ones that have a cult following (e.g. Pulp Fiction, American Beauty) and somehow re-fit the prescription to the actual, as if box-office success, a cult following (e.g. Coen Brothers), or awards, confer credence or validity that somehow overrides a set norm. That approach leaves us with no objective standard by which to judge story art.

Romanticism, on the other hand, is an objective standard. Box-office revenue, aggregate sales, or aggregate sales net of budget, are also all objectively measurable standards. Those, however, are standards of commercial success, not of artistic merit. The problem for educators is that once they loudly proclaim that they teach a how-to-make-it-in-Hollywood approach, they are compelled to reconcile awards and commercial success to their edicts rather than admit no knowledge of why some prescribed things fail and the ex-ante criticized scripts succeed; success in this case includes getting a screenplay optioned or made into a film. Robert McKee, however, remains the standout exception to this trend of ex-post rationalizing.

Rand attributed the growth and increasing popularity of Naturalism, and the reduction and corruption of Romanticism, to the progressive disintegration of culture, paralleling the disintegration in the fields of ethics and politics.

Citizen Kane is a wayward, purposeless story, essentially an inferior screenplay.

The Academy, like its literary counterparts in the Man Booker, Pulitzer, and Nobel prizes, has never laid down an objective standard for judging art. In the literary arena, the inferred standard is Naturalism or Existentialism. The Academy has rewarded both romanticist and naturalist movies in the Best Picture and Best Screenplay categories, albeit the trend of the last eleven years is ominously consistent (in favor of Naturalism), except in the Best Foreign Film category, where those of the 6,000 working professionals who vote on it, must actually attest that they have seen it.

Film critics however, have long since completed their journey into the dark world. For sixty consecutive years (1952-2012), film critics classified a wayward, purposeless examination of an unhappy newspaper baron (Citizen Kane) to be the greatest film of all time, offering little more than new techniques at the time and a gimmicky narrative structure as the reasons thereof. Citizen Kane is a wayward, purposeless story, essentially an inferior screenplay.

Perhaps, like their literary counterparts, they did not dare to state the real reason—Orson Welles made Naturalism chic and initiated the debasement of humanity in movies in 1941.

7. Low-level and Bootleg Romanticism

Romanticism requires a well-ordered, well-thought-through plot. It is difficult, but it is the superior form of art.

In a January 1965 essay titled Bootleg Romanticism, Rand stated that romantic art is virtually nonexistent but for crime thrillers, which she designated as “the kindergarten arithmetic of which the higher mathematics is the greatest novels of world literature”.

In lower-level Romanticism, there is an obvious good and bad side from the start (e.g. cops & robbers, detectives and serial killers etc.), and a lack of an internal value-clash for the principal characters, and thereby of internal growth or discovery.

Rand used the term Bootleg Romanticism to describe situations where even lower-level Romanticism such as fantasies or crime thrillers are portrayed in a way whereby the heroic actions are performed with a tongue-in-cheek slant, the subtext telling the audience not to take them seriously, i.e. in effect saying “this is just for laughs, it’s not emotional fuel for your soul.” Romanticism requires a well-ordered, well-thought-through plot. It is difficult, but it is the superior form of art.

8. Illustrations of Romanticism—Movies

To make our search for Romanticism contemporary, I state five 21st Century examples of screen stories that, in my opinion, best exemplify Romanticism. There are of course, many more, especially if one goes back fifty years, but these are among the purest of the last ten years from the ones I have seen.

I. The Counterfeiters (2007): Based on a true WWII story, this German language film is a telling of an incredible internal value-clash within a Jewish artist, Salomon Sorowitsch (Sal). Sal makes a living as a forger of passports and currency. The Nazis hunt him down and send him to a concentration camp. Here, he uses his portraiture skills to get himself a better bunkhouse and food.

I. The Counterfeiters (2007): Based on a true WWII story, this German language film is a telling of an incredible internal value-clash within a Jewish artist, Salomon Sorowitsch (Sal). Sal makes a living as a forger of passports and currency. The Nazis hunt him down and send him to a concentration camp. Here, he uses his portraiture skills to get himself a better bunkhouse and food.

The Nazis want to use him to forge the British Pound and the U.S. dollar. Initially motivated by survival, he is conflicted by the fact of the counterfeiting assisting the Germans in the war, and further conflicted by the pride he takes in his work—he has never been able to perfect his counterfeit of the U.S. dollar, and the Germans are throwing money at it. His fellow prisoners are on both sides of the debate—is it better to die honorably now, or die after helping the Nazis while retaining a slim possibility of escape? Sal engages in covert delaying tactics to buy time, which starts an engrossing cat-and-mouse detection game. It won the best foreign language film Oscar for 2007.

II. The Dark Knight (2008): Even Metacritic picked this one as one of the best superhero films, and one of the best of the decade. The Batman, the DA, and the Police Commissioner combine forces to stop rampant crime in Gotham City, but they seem unable to stop the relentless nihilism of The Joker (“This city needs a classier kind of criminal and I’m going to give it to them”). The Joker sets up a moral experiment on the seas that ends up with a result opposite to what he desired—it lifts convicted felons into moral uprightness rather than turn ordinary citizens into killers. His next experiment succeeds however, as The Batman, his alter ego the other male in an uneasy love triangle, miscalculates, letting the love of his life die, in order to rescue the personification of virtue and courage in the city, the DA, who loves the same woman. The DA survives. However, facially scarred in the fire, and emotionally scarred by the loss of his fiancée, he loses faith in virtue itself, and is turned by The Joker into Two-Face, an eccentric, evil killer in love with nihilism.

II. The Dark Knight (2008): Even Metacritic picked this one as one of the best superhero films, and one of the best of the decade. The Batman, the DA, and the Police Commissioner combine forces to stop rampant crime in Gotham City, but they seem unable to stop the relentless nihilism of The Joker (“This city needs a classier kind of criminal and I’m going to give it to them”). The Joker sets up a moral experiment on the seas that ends up with a result opposite to what he desired—it lifts convicted felons into moral uprightness rather than turn ordinary citizens into killers. His next experiment succeeds however, as The Batman, his alter ego the other male in an uneasy love triangle, miscalculates, letting the love of his life die, in order to rescue the personification of virtue and courage in the city, the DA, who loves the same woman. The DA survives. However, facially scarred in the fire, and emotionally scarred by the loss of his fiancée, he loses faith in virtue itself, and is turned by The Joker into Two-Face, an eccentric, evil killer in love with nihilism.

The Batman, in an action that concretizes the ‘inspiring art as emotional fuel’ abstraction, offers to take the blame for the murders committed by the DA, to ‘preserve the possibility for Gotham that the good can persist to the end’. The sterling image of the DA as Gotham’s White Knight is to be preserved as though it was an art form. In the final scene, the Commissioner reluctantly takes up the offer, setting the police dogs to chase after The Batman, now Gotham City’s Dark Knight. The insightful concretization of the two moral experiments, and the personification of nihilism brilliantly portrayed by Heath Ledger, in addition to the outstanding screenplay, led me to categorize this story as high-level Romanticism.

III. Conviction (2010): Based on a true story, a mother of two young children, works relentlessly for eighteen years to free her brother, an ex-small-time-felon, wrongly convicted of murder. The brother happens to rob the victims’ home moments before the murder, which places him at the scene. The mother’s obsession with the pursuit ends up with her having to put herself through law school, suffer divorce, estrangement from her children, and multiple setbacks via a judicial system uninterested in the truth, before she finally realizes her goal.

III. Conviction (2010): Based on a true story, a mother of two young children, works relentlessly for eighteen years to free her brother, an ex-small-time-felon, wrongly convicted of murder. The brother happens to rob the victims’ home moments before the murder, which places him at the scene. The mother’s obsession with the pursuit ends up with her having to put herself through law school, suffer divorce, estrangement from her children, and multiple setbacks via a judicial system uninterested in the truth, before she finally realizes her goal.

IV. The Lives of Others (2006): Made with a shoestring budget of $2 million, the theme of this German language film is the surveillance of the citizenry in a police state, pitting the best of the citizens against the secret police. What is uplifting in this strong values clash is that the Stasi officer on the straight and narrow is edged to the right side of wrong by a sonata, and driven further into it by a stolen book of poetry, even as the police state pushes upstanding citizens into the wrong side of right. The feel of authenticity is the hallmark of this gem; they used the real surveillance machine, recreated the 1980s Berlin in streets that have remain unchanged, and the screenplay got more than a once-over from people who experienced the policing on one side or the other. It got the gong for the Best Foreign language film Oscar for 2006.

IV. The Lives of Others (2006): Made with a shoestring budget of $2 million, the theme of this German language film is the surveillance of the citizenry in a police state, pitting the best of the citizens against the secret police. What is uplifting in this strong values clash is that the Stasi officer on the straight and narrow is edged to the right side of wrong by a sonata, and driven further into it by a stolen book of poetry, even as the police state pushes upstanding citizens into the wrong side of right. The feel of authenticity is the hallmark of this gem; they used the real surveillance machine, recreated the 1980s Berlin in streets that have remain unchanged, and the screenplay got more than a once-over from people who experienced the policing on one side or the other. It got the gong for the Best Foreign language film Oscar for 2006.

V. Agora (2009): Atheist Spanish writer-director Alejandro Amenábar reconstructed the tale of Hypatia, a female philosopher-astronomer-mathematician of the late 4th century Roman Egypt. U.S. audiences only got a limited theatrical release probably because of the overt anti-Christian stance. No film has so openly celebrated the epistemology of reason over faith. As the Pagans are fighting a losing war against the invading Christians, Hypatia determinedly pursues scientific truth, saving important scrolls from the library destroyed by the Christians. Of her three prominent pupils, two (Orestes and Davus) are in love with her; the third (Cyril) becomes an aggressive Christian missionary.

V. Agora (2009): Atheist Spanish writer-director Alejandro Amenábar reconstructed the tale of Hypatia, a female philosopher-astronomer-mathematician of the late 4th century Roman Egypt. U.S. audiences only got a limited theatrical release probably because of the overt anti-Christian stance. No film has so openly celebrated the epistemology of reason over faith. As the Pagans are fighting a losing war against the invading Christians, Hypatia determinedly pursues scientific truth, saving important scrolls from the library destroyed by the Christians. Of her three prominent pupils, two (Orestes and Davus) are in love with her; the third (Cyril) becomes an aggressive Christian missionary.

Orestes chases Hypatia and power; he risks losing his power over Alexandria because of his love for Hypatia, but only Davus can save the intransigent Hypatia from torture at the hands of Cyril’s mob. Agora is the most romanticist and aesthetically high-standard film I have ever seen. Great performances, eye-catching cinematography, and concretizations of various abstractions—the conflict of reason versus faith, the joy of discovery, the determination of history by the philosophical convictions of its age—are all integrated into a story of love: a love triangle, the love of knowledge, and the love of a man for a woman based on the values she pursues.

9. Illustrations of Romanticism—Television

Television drama serials such as Mad Men, Breaking Bad, House of Cards, and Homeland are breaking new ground. They involve multiple characters in relentless pursuit of their respective goals, albeit the world is typically portrayed as a moral grey, only the shades differ. As is required by TV drama, the story is held together by a place (the ad agency in Mad Men, Congress in House of Cards) or a person (family man Walter White making difficult choices as he faces imminent death from cancer in Breaking Bad, a marine in search of an ideology in Homeland). House of Cards is a pure pursuit of power; future seasons may concretize the effect of such a strategy on the lives of its principal proponents. In each case, decisions abound, and the plot is driven entirely by the choices made by the principal characters, albeit there is an absence of a fundamental value clash.

Television drama serials such as Mad Men, Breaking Bad, House of Cards, and Homeland are breaking new ground. They involve multiple characters in relentless pursuit of their respective goals, albeit the world is typically portrayed as a moral grey, only the shades differ. As is required by TV drama, the story is held together by a place (the ad agency in Mad Men, Congress in House of Cards) or a person (family man Walter White making difficult choices as he faces imminent death from cancer in Breaking Bad, a marine in search of an ideology in Homeland). House of Cards is a pure pursuit of power; future seasons may concretize the effect of such a strategy on the lives of its principal proponents. In each case, decisions abound, and the plot is driven entirely by the choices made by the principal characters, albeit there is an absence of a fundamental value clash.

Television’s great advantage is the long story arc of the season. TV’s 50-minute stories, interrupted by commercials, were conveyed in the dialogues, violating the show, don’t tell doctrine. By making shows non-episodic and using multiple protagonists, television has supplied its writers multiple variables to play with, and plenty of time (when is the last episode of the last season?) to resolve the conflicts so set up. This makes for unpredictability—in a good way, in that story turns take us by surprise, or at least are not predictable because there are so many different paths a multi-protagonist long story can take. Further, end-of-episode and end-of-season scenes can be designed as cliffhangers—further factors that draw in the numbers and the ratings.

Television’s great advantage is the long story arc of the season. TV’s 50-minute stories, interrupted by commercials, were conveyed in the dialogues, violating the show, don’t tell doctrine. By making shows non-episodic and using multiple protagonists, television has supplied its writers multiple variables to play with, and plenty of time (when is the last episode of the last season?) to resolve the conflicts so set up. This makes for unpredictability—in a good way, in that story turns take us by surprise, or at least are not predictable because there are so many different paths a multi-protagonist long story can take. Further, end-of-episode and end-of-season scenes can be designed as cliffhangers—further factors that draw in the numbers and the ratings.

However, so long as film stories with fantasy elements have strong allegories to the real world in terms of the moral dilemmas faced by the protagonists, they are also likely to do well, and indeed, they do so (refer Appendix I for the list of biggest earning movies of this century). The driver of this box-office performance is not the blockbuster budget, it’s the strength of the story—of its Romanticism, and of the ability of its allegories to relate to the real world, coupled with what Aristotle called ‘spectacle’—the visually stunning special effects, the physicality of the conflicts, and the physical beauty and emotional honesty of the star attractions.

10. Audience reach of screen stories

One research report (Market Watch) suggests that less than one in two Americans read a novel a year, while Pew Research suggests that one in four do not read any kind of book. A fiction book that sells over a million copies is considered a bestseller. Every year, some new books break into that zone.

Including DVD hires and downloads, several Hollywood movies are seen by over a million people every year; the highest-grossing films have reached over a hundred million people. Successful TV drama has ‘live’ audiences in excess of a million. Over 10 million people watched the final episode of Breaking Bad. The drama series Lost averaged 17 million viewers; The Walking Dead’s finale was watched by 15.7 million viewers. The numbers increase when you add the internet downloads and DVD hires. As a whole, screen stories have a wider reach than literature—many that never read books, do watch films or television, whereas the converse is far less true.

Every year, more screen stories (as compared to novels) exceed a pre-set Reach Watermark (whether one sets it at one million or ten million). It is, quite simply, easier to sit in front of a screen for two hours than read for six to eight hours. A TV drama serial, however, can take ten to twelve hours of viewing for one season, but it still easier than reading large literary works, which can take just as long to read. Further, a movie audience is close to 100% captured for the duration; very few leave the theatre after the film starts. Relatively, both serial TV drama and books will suffer lost audiences.

11. Corrupted end-values and symbolic monstrosities

In her essay, “The Esthetic Vacuum of Our Age”, Rand remarked that Naturalism was in fact no longer presenting the statistical average, but the worst in humankind. This was the sort of depravity, which made the audience feel “at least I am not that that bad,” with the consequence being a release from aspiring to be the best one can be, a moral license to let go and stop trying, i.e. the very antithesis of what art ought to be doing. Some of our illustrations of Naturalism (e.g. Disgrace, There will be Blood) do precisely that by reflecting an existentialist view of life.

The screenwriting equivalent of this phenomenon is expressed by McKee as the antiplot—a de facto celebration of vice, rather than virtue, whereas McKee’s archplot reflects what we call Romanticism, and his miniplot (minimization of values) reflects the statistical average Naturalism.

12. A framework for detecting Romanticism

I put forward a seventeen-question based framework for detecting Romanticism, with the degree of Romanticism being greater for the higher number of affirmative answers. It is important to note that the question of cinematic aesthetics is relevant. Everything from authenticity in costume and set design to cinematography and performances matters in terms of engagement; higher the engagement with the narrative, higher is the uplift felt by the participant. Equally important to note is the issue of the objectives—they need not be ones that an objectivist would pursue.

a. Do we have at least one major character that wants something badly?

b. Is this want, triggered by an exogenous event? (the first cause must be exogenous, not driven by the character who himself/ herself has the objective)

c. Is there a strong conflict of diametrically opposed values in the story?

d. Is the goal, sensible as well as improbable (due to conflict or difficulty), but not impossible?

e. Are the characters taking purposeful and sensible action in pursuit of their wants?

So what is a sensible goal, sensibly pursued? In Jaws, a shark attack kills people. This exogenous event causes the Sheriff to want to eliminate the shark. This is a sensible goal. He pursues it sensibly by hunting it down. In The Great Gatsby, a poor man pretends to be rich to impress a woman. He then joins the army because he is penniless, and when he returns from the war, makes a fortune by illegal means. He wants to impress the woman he is love with. That seems sensible enough for a man like that. However, rather than using his wealth to locate her easily using private detectives, and then using it to spend lavishly on her, he uses it to throw wild and extravagant parties for strangers, parties which he himself rarely attends. This is incongruous.

Virtually none of David Lurie’s actions in Disgrace make any sense, whereas, in Breaking Bad, Walter White has only a few months to live, so he wants to make a fast buck for his family. That seems plausible. He finds a way to do that using his knowledge of chemistry. That is sensible, purposeful action. In his situation, it makes sense. The morality of it is a separate matter—the moral question of whether to leave a virtuous legacy or money in an either/or situation can be answered even by the protagonist taking the wrong road—by showing the consequences of taking the wrong road. Romanticism does not imply having virtuous goals and happy endings (achieved values) as the norm. Good drama, however, requires having sensible goals, and pursuits that appear sensible when placed in their context.

f. Is each subsequent event caused by the previous events, coupled with the actions of the purposeful characters reacting to it?

g. Is the conflict resolved at the end in a way that the story cannot continue?

h. Does the resolution change the story world, a character/s, or both, for the better?

i. Are the characters consistent throughout the story?

j. Are the manufactured realities, if any, consistent throughout the story?

k. Is there no resort to coincidences to propel the story forward, or to end the final conflict?

l. Are the aesthetic qualities (set and costume design, accents, dialogue) of the screen story authentic vis-à-vis the setting chosen?

m. Are the aesthetic qualities (cinematography, pace, performances) gripping? At the storyboard stage, can the concretization be made visually spectacular?

n. Is the story authentic vis-à-vis its major theme (e.g. evidence collection procedures, the way a courtroom functions, the way poetry is taught (e.g. in Dead Poets Society)?

o. Are there no loopholes in the story?

p. Is the story told without resorting to excessive exposition via dialogue/voiceover, with abstractions concretized rather than didactically explained?

q. Are there unexpected twists and turns, which, with the benefit of hindsight, appear logical?

13. Improving the Romanticism of a story

Our 17-question framework is useful, not only for passing judgment with objective consistency, but also for restructuring a story to make it more romanticist.

Let us take The Butler (2013), a purportedly historic, slice-of-life account of a White House butler. The Butler breaks the cardinal rule of a good dramatic story—the protagonist is almost completely passive, and his goal is a very low-level one—being safe rather than sorry; staying out of trouble.

Let us take The Butler (2013), a purportedly historic, slice-of-life account of a White House butler. The Butler breaks the cardinal rule of a good dramatic story—the protagonist is almost completely passive, and his goal is a very low-level one—being safe rather than sorry; staying out of trouble.

Cecil Gaines, the butler, has a son who becomes a political activist for desegregation. If the story centered on the son instead, the closing images (where father and son reconcile as the son awakens the conscience of the father), the personalities, and many of the events, could be the same, but this point of view change could, with a few more tweaks, turn this story into a largely romanticist one.

The Butler however, was perhaps intended to be propaganda Naturalism, rather than a romanticist film. Our framework will work easier as a detection and correction mechanism when the intention is right, but flaws have crept in the execution (i.e. writing) of a story.

14. Concluding comments

The can-do outlook engendered by romanticist art can make us all perpetually young in spirit. However, the scorn of the pseudo-intellectual literati against it is cloaked in the well-disguised garb of awards; only minds alerted to this phenomenon can catch it. Screen stories are now the most dominant form of story art. The corruption of screen stories by the literati is incomplete. It makes our continuing search for Romanticism worthwhile.

The survival of Romanticism may be partially attributed to romanticist fantasy stories that facilitate spectacle such as Superman, Harry Potter, Twilight, and others. They succeed at the box-office in part due to spectacle. Romanticism has a natural, as-yet-uncorrupted, fan base (the very young). Perhaps its survival could also be partly attributed to Aristotle having slipped in under the radar as the anointed guru of screenwriting.

Most film critics are either subconsciously existentialist, or operating in a vacuum, their critiquing simply a subconscious reaction wrapped in flowery language. In either case, they are no better than the average Joe on the street, and undeserving of their status.

Anyone can promote Romanticism. It would be instructive to read The Romantic Manifesto: A Philosophy of Literature, by Ayn Rand. A Facebook group, Romanticism Watch, has been created to act as a sentry-force on high alert—the intent is to spot, and promote, romanticist works of art. Feel free to join the crusade.

Note: This article first appeared, largely as is, on the site of The Story Department, under the heading “Romanticism in Hollywood.”

Appendix I (Useful Hyperlinks):

1. Ranking of highest-grossing films, box-office earnings only (adjusted for inflation)

2. Ranking of highest-grossing films, collateral revenue included (adjusted for inflation)

3. List of Best Picture Academy award winners by year

4. List of Golden Globe Best Motion Picture Drama winners and nominees

5. List of BAFTA Best Film award winners and nominees

Appendix II: Filmography

An illustrative selection of films by their dominant slant, drawn from what I have seen, and containing mostly recent works (some historical works are included for illustrative purposes). Readers could well come up with their own list. Many stories of superheroes, sci-fi, rom-coms, fantasy, animations, and westerns could be romanticist (e.g. Star Wars, Star Trek, Twilight, Superman, The Matrix), so I have used only one ingenious illustration——Pirates of the Caribbean. The Curse of the Black Pearl, being the first, gets the nod for originality.

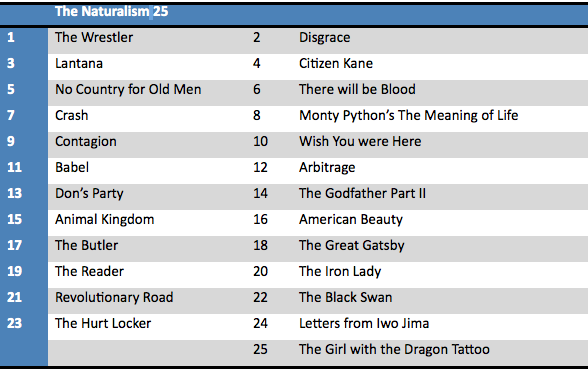

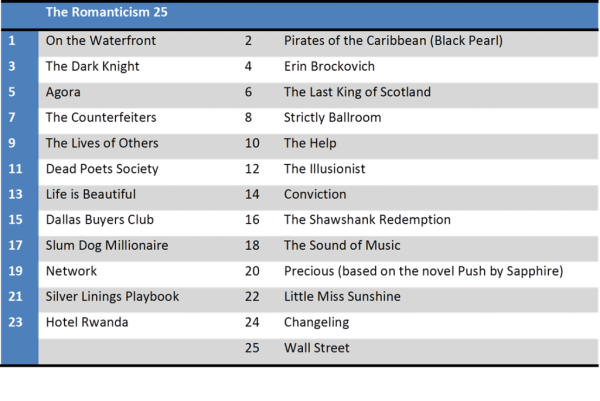

The Naturalism 25

The Romanticism 25