Translating deep thinking into common sense

A Sequel to We the Living?

By Marco den Ouden

May 12, 2023

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

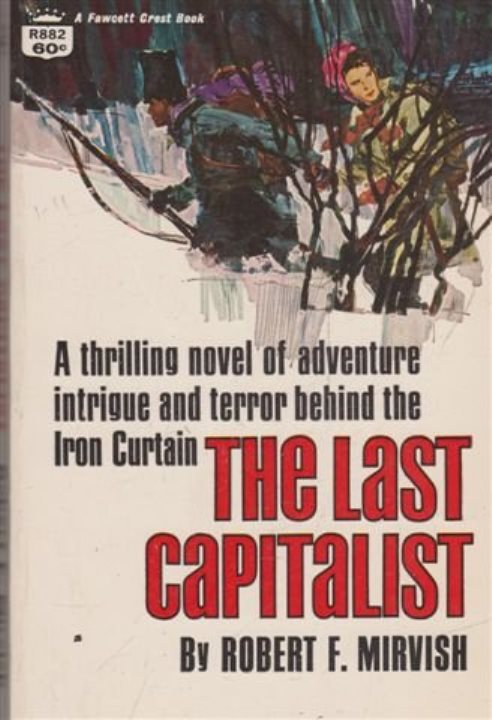

Book Review: The Last Capitalist by Robert F. Mirvish, Fawcett Crest, 1966

There’s only a passing mention of him in Wikipedia as the younger brother of Honest Ed Mirvish, a Toronto businessman, discount retailer and theatrical impresario. However, his obituary in 2007 notes that Robert F. Mirvish was a radio officer with the U.S. Merchant Marine during and after World War II. Undoubtedly his seafaring life informed many of his fourteen novels, many of which revolve around sailors. His stories sold well, selling over 150 editions in a dozen different languages.

In 1972 I came across his 1963 novel The Last Capitalist and, as an avid Ayn Rand fan, snapped it up and read it with great enthusiasm. Now after all these years I read it again and it is even better than I remembered. The novel could be loosely described as a sequel to We the Living set about twenty years later. Sadly, the book is out of print, but you can find copies from secondhand book dealers online.

Mirvish may have been familiar with Ayn Rand’s novels. Certainly, there is a philosophical flare to the novel.

Since it was published in 1963, Mirvish may have been familiar with Ayn Rand’s novels. Certainly, there is a philosophical flare to the novel. But I suspect that his observations are his own and may be based on experience. It is entirely conceivable that while in service with the Merchant Marine, he was stuck in Murmansk, the setting of the novel, and observed much of the background activities that make up the backdrop of the novel.

Murmansk was a major shipping port in wartime Russia. It sits on the Kola Bay, an inlet of the Barents Sea. Despite its northern location and snowy winters, its waters remain ice-free year-round due to the North Atlantic Current. As Wikipedia notes:

During World War II, Murmansk was a link to the Western world for the Soviet Union with large quantities of goods important to the respective military efforts traded with the Allies: primarily seeing military equipment, manufactured goods and raw materials brought into the Soviet Union. The supplies were brought to the city in the Arctic convoys.

The destruction of the city was “rivaled only by the destruction of Leningrad and Stalingrad… The Luftwaffe bombed the city 792 times during World War II.” Nevertheless, “Murmansk served as a transit point for weapons and other supplies entering the Soviet Union from other Allied nations.”

This sets the stage for an intriguing and exciting novel of conflicting cultures and the struggle for survival in the war-torn city.

The main protagonist is Dmitri, a twelve year old boy. “Dmitri was twelve years old only as age is reckoned by time. The eyes, the face, the expression of authority and intelligence were ageless, and rare, as such faces always are, in either adults or children.” He had learned hunting and trapping from his father before he left to join the war effort, never to return. He learned to think for himself and to think on his feet. From an older boy he learns to scavenge the war dead on the battlefield for things he can trade with incoming foreign sailors.

The antagonist in the story is Deputy Arnoldov. He seizes a group of the young traders and the older boy is taken for military service. Dmitri is left to lead the remaining bunch after they are released. Arnoldov is an opportunist and Dmitri notes the relish with which he smokes a confiscated American cigarette. Dmitri’s intuitive understanding of Arnoldov’s psychology serves him well in the days ahead.

Dmitri also understands the dangers of remaining in the city. He leads his band of young traders to a cave in the hills around Murmansk, the skills he learned from his father coming in handy.

Another protagonist is an American, Grant Hollis, who has been stuck in Murmansk for a year. Hollis lives in a wooden longhouse built to house stranded foreign sailors. Like most of them, he likes his shots of vodka. But his passion is to get out of this god-forsaken place and back to sea. To while away the time, he whittles wooden figurines. Dmitri’s growing sense of what is valuable to whom, the niche markets that fuel capitalist enterprise, leads him to trade vodka for Hollis’s carvings.

Hollis offered to give his carvings to the boy for free.

Hollis offered to give his carvings to the boy for free.

“I do not take gifts.”

“Why not?”

“I do not take things without giving something in return. To take without that understanding gives you an advantage over me… They would not really be mine. You would be able to say what I can or cannot do with them. I would not truly own them.”

Hollis perplexes Dmitri. “The American had such detachment about possessions… It was contrary to everything Dmitri had been led to believe about Americans, and people from the capitalist world generally. The primary difficulty was that Dmitri had been raised on slogans and was only now learning that people did not necessarily conform to government edict.”

Even Arnoldov “patently was not a stereotype. Arnoldov was precisely the sort of man a Russian deputy was not supposed to be…. The deputy had a voracious acquisitiveness and an air of chicanery, both glossed over by a ‘hail-fellow, well-met’ attitude.”

One other primary character is introduced. Katya Markova. “She had a sharp, alert intelligence, but also lately, since her marriage, an intransigence that was viewed by her superiors with suspicion.” She had had a good education because her father had been a revolutionary war hero. Her marriage was what undid her standing in the party.

Rodion, her husband, was a Ukrainian, and as it turned out, a Ukrainian nationalist. She had been attracted by his intelligence and irreverence. “His probing jests, his ability to puncture party cant and slogan, had often sent her own alert thinking careening off into strange, non-doctrinaire byways.”

But they had been together for such a short time, and married for only a week when he was arrested for his activities. “Her years of conformity had merely been pinpricked.” And with an unblemished personal record, she had been allowed to continue with her career as a schoolteacher, but had been reassigned to Murmansk. Now she learned that formal schooling was all but dead in the city. Her assignment was to bring the street urchins to heel. To bring them back under the aegis of the government for re-education. To do this she had to gain the confidence of the youngsters on the street and negotiate a meeting with Dmitri. And because of a labor shortage, she also had to work at the Intourist hotel where many American and Western sailors hung out at the bar and restaurant.

“I do not take things without giving something in return.”

These characters drive the story with increasing suspense to a dramatic conclusion. I don’t want to give away too much of the story, but suffice to say that early on Dmitri has already made plans to accumulate foreign money and to escape to Norway with those of his band who want to join him. Over the course of the story he rescues Nadya, a girl a bit younger than himself, from a bombed-out building during an air raid. She becomes devoted to him and he pledges to take her with him when they escape.

Katya, in her efforts to get in touch with Dmitri, meets Vladimir, one of the younger members of his band. She decides she can gain his trust by buying something. He is justifiably suspicious of her. “She was the one who had been sent from Moscow to bring them all back under government control.” She had been chatting up a number of the street kids over the last few days. He shows her a wooden carving.

“Why, that’s very nice,” she said. “May I hold it?”

“It is a thousand rubles,” he said.

“A thousand rubles!”

“That is the price.”

“But that is more than a month’s wages.”

“Then you are underpaid,” he said cheekily.

She had savings as there was little to spend money on in Murmansk. She arranges to meet him the next day. The next day, after watching her for some time to make sure it wasn’t a trap, Vladimir meets her and they conclude the trade. But something comes over her as she holds the object. What Mirvish writes next is a profound description of the meaning of personal property. It is a pivotal moment in the book.

“She held the carving in her hand experiencing a peculiar emotion. This carving belonged to her. It was something intimate and personal. It was neither practical nor educational. It was an ornament, an object of pleasure. It was a thing outside of anything she had ever owned before. One could not feel thus about clothes, about food, about lodgings and furnishings. These were allocated proportionately by the state, depending on one’s utility. Intrinsically valuable, but utilitarianly worthless objects such as this carving were something else again entirely. It was without value except to someone who drew spiritual pleasure from it, such as herself. She felt a sense of happiness in her ownership of it which served to compound its value. Everything was gone, her complete integrity as a party functionary, her husband, her school in the Crimea. But this carving belonged to her.”

Later Katya meets Hollis at the Intourist. He is immediately attracted to her, as are many of the sailors. She rebuffs him at first. But then she learns he is the carver.

The nightly air raids start to diminish as the tide of the war is turned. Everyone knows the nudge nudge, wink wink arrangement with Andropov must end. But how will it end? Will Dmitri, Nadya, and the boys make it to Norway? Will Hollis finally find his way back to the sea? And what of Katya?

The book is not as profound as We the Living but there are some striking parallels to it.

The book is not as profound as We the Living but there are some striking parallels to it. It effectively shows that life under the Soviets twenty years later has not changed significantly since Kira’s struggle in Petrograd. It shows the same dreary officialdom, the same bureaucratic nightmare, the same rank opportunism, the same turmoil faced by those who can think for themselves. Throw into this the drama of war and the clash of cultures as West meets East due to a wartime alliance and you have an intriguing novel with noble and heroic characters you admire as they struggle against an inhuman system.

I’d love to see this book re-issued in a new edition. I think it would still find an audience today.

The Last Capitalist is available online at Open Library.