Translating deep thinking into common sense

A Hero for the Generations: The Enduring Romanticism of the Tarzan Story

By Marco den Ouden

March 9, 2024

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Book Review: Tarzan in the Heart of Darkness: (Inspired by Edgar Rice Burroughs), by Walter Donway, Publisher: Romantic Revolution Books, 2018

I remember those evenings I sat beside dad on the couch as he read the latest second-hand Tarzan book he had bought at the Strand book shop in New York City on his business trip. The stories inspired me to never settle for less than the ethos of man’s nobility.

Walter Donway

Walter Donway had a love affair with Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan novels from the time his father started reading them to him.

Walter Donway had a love affair with Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan novels from the time his father started reading them to him. He immediately grasped the romanticism of the novels, the projection of a larger-than-life hero, someone he could look up to, admire, and emulate.

In her “Introduction” to the 25th anniversary edition of The Fountainhead, Ayn Rand wrote that “Romanticism is the conceptual school of art. It deals, not with the random trivia of the day, but with the timeless, fundamental, universal problems and values of human existence. It does not record or photograph; it creates and projects. It is concerned—in the words of Aristotle—not with things as they are, but with things as they might be and ought to be.”

Pulp fiction like the Tarzan novels and many of today’s crime novels “are the product, the popular offshoot, of the Romantic school of art that sees man, not as a helpless pawn of fate, but as a being who possesses volition, whose life is directed by his own value-choices.”

When Donway conceived of the idea of writing a new version of the Tarzan story, one steeped in the history of that era, he wrote to the estate of Edgar Rice Burroughs “to offer the unpublished novel under any standard conditions they apply,” but got no reply. Nor did he get a “message of any kind challenging my right to publish.” So, with Edgar Rice Burroughs’s copyright on the Tarzan books long expired, he went ahead and self-published the novel.

Donway’s tribute to the Tarzan novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs is superb.

Donway’s tribute to the Tarzan novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs is superb. In a brief historical note, he sets the context for this new take on Tarzan. At the time of the Tarzan stories, Africa was a hotbed of colonial exploitation. The most notorious was Belgium’s King Leopold II who established the horribly misnamed Congo Free State which became his personal fiefdom. He made use of the widespread slave trade to make the Congo a slave state, exploited for its wealth by the use of slave labor at the turn of the twentieth century. Donway notes that Joseph Conrad’s novel, Heart of Darkness, is “about white men in the Belgian Congo who were corrupted utterly by their role as slave masters.” But this “Heart of Darkness” “extended across Africa to lands controlled by the sultans of Tanzania and Zanzibar.”

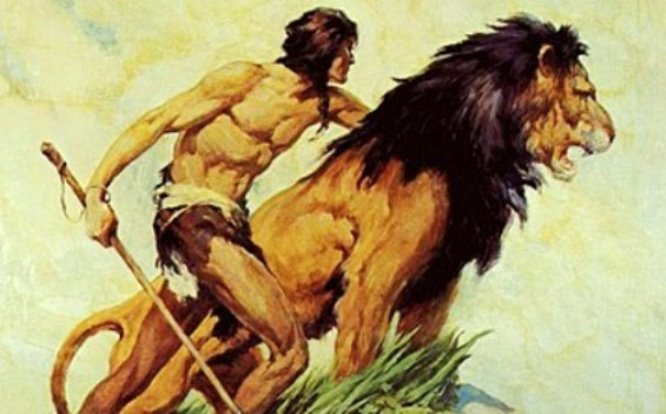

Donway’s new take on Tarzan has a fifteen-year-old Tarzan, strong and virile after being raised by the great apes, joining forces with N’Kimba, a young and fearless Maasai woman, in her quest to save her parents from the clutches of Leopold’s slavers. The rescue attempt is a rousing good story, full of intrigue and action. Tarzan is shown for the resourceful and intelligent young man he is, a youth who thinks on his feet, keenly observes his surroundings, and plans their assault on Leopold’s stronghold. He is also the ultimate specimen of virility and strength. Think of a young Arnold Schwarzenegger. Broad-shouldered and strong.

N’Kimba’s parents join them after their rescue as they continue to cross the continent. Tarzan begins to understand the nature of slavery under N’Kimba’s tutelage. A difficult task as they do not speak the same language. Indeed, Tarzan only knows written English which he learned from the picture books his parents left behind in their jungle home. He has no conception of the sounds associated with the “little bugs” on paper. N’Kimba painstakingly teaches him through gestures and speaking to learn a spoken language, not English.

Together they venture across Africa, from the Congo to the shores of Lake Victoria and on to Kampala and from there to Kisumu, the western terminus of the six-hundred-mile railroad to Mombasa, now in British hands. The British are determined to wipe out slavery in Africa and the troop meets up with Assistant District Commissioner Barclay. Together they plot to free the slaves of the notorious slaver Khalid bin Barghash from his stronghold on Zanzibar.

As Ayn Rand put it so well, “Romantic art is the fuel and the spark plug of a man’s soul; its task is to set a soul on fire and never let it go out.” This what the Tarzan stories do.

Along the way we also meet the creatures of the jungle, from the dangerous to the resourceful. Tarzan tames the wild elephant, Tantor, and they become fast friends and allies. They also fight off a pack of lionesses hungry for the kill who want them for dinner. And, of course, no Tarzan story would be complete without Tarzan’s blood-curdling, chest-thumping cry of the bull ape, which he uses to strike terror into the hearts of his enemies.

All this makes for a rollicking good tale, full of action and intrigue, wit and intelligence. A most worthy tribute to Burroughs and the original Tarzan stories. I hadn’t read the original Tarzan of the Apes in decades, but Donway’s book inspired me to order a copy from Amazon so I can read it again!

As Ayn Rand put it so well, “Romantic art is the fuel and the spark plug of a man’s soul; its task is to set a soul on fire and never let it go out.” This what the Tarzan stories do.

————–

Below, I have included a poem about Tarzan by Walter Donway:

Tarzan of the Apes

(For Dad, who showed me, all can be forgiven)

I knew that you would come for me,

Come dropping, forest demigod,

From loftiest, implausible

Green jungle high roads that you trod.

Liege lord of titan trees that sweep

Mere heaven, noble imago

Of man as sure as marble slimmed

To life by Michelangelo,

You would appear upon my path,

As sun will touch a single tree.

And with your eyes as wild and kind

As freedom, you would gaze on me,

And nod, impartial as a beast,

Or God, and I would go, and soon

We’d fly as high as dream desire

Through trees beneath a jungle moon.

And we would never tire, fight

And never doubt. Our fathers’ knives,

Baptized in fierce Bolgani’s blood,

Would bless the battles of our lives.

We’d summon good Tantor and tease

Malicious Sheetah’s snarling smile.

We’d stride as nude and beautiful

As beasts to baffle Satan’s guile.

At manhood’s noon, our two great hearts

Would stay the lion’s breath above

The golden woman’s blameless breast,

And slay the lord of Death—for love.

And never taste the fatal fruit

Of fear, and never die, or die

Each day and never care what ate

Our bones or where our bones might lie.