Translating deep thinking into common sense

A Meeting of Minds

By Walter Donway

March 27, 2025

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Myron Kandel’s apartment was the relic of another age, the grand, sprawling prewar on the Upper West Side that young professionals with trust funds envied from the sidewalk. Seven rooms, fourteen-foot ceilings, bookshelves stacked in precarious columns of old philosophy and history books, their spines cracked from years of rereading. He paid $1,500 a month for what the market deemed worth $15,000 a month, and this knowledge gnawed at him. The old rent-control laws had frozen him in place, a vestigial remnant of an era when a City College professor could still afford a view of the Hudson River.

His apartment was a kingdom of unoccupied spaces. He sometimes paced through it as if it were a chessboard of decisions—should he rent out the spare bedroom to a coed? A struggling grad student? The homeless? The problem with people was that they came with needs, expectations, and noise. He had had enough of people in his time, most notably his colleagues, first with their “New Leftism,” the last best hope of the defeated Marxist dream. Their years of rationalizing, sometimes cheering on, the “revolution,” with its safe campus violence. Then came their “critical theory” and “decolonization” and all the postmodernism that passed for academic discourse. He had spent his career fighting their ideas, only to find that new generations had arrived to take over academia on behalf of that bastard born of neo-Marxism and German Idealism—postmodernism —and they had outlasted him. When he retired, no one came to say goodbye. He packed his own boxes and carried them out himself.

Today, at dusk, he went walking in Riverside Park. He wasn’t naïve—he knew the city had changed, had watched it shift, and not always for the better. He had been a Navy SEAL once, long before his years in academia, before the long decades of lecturing young minds on philosophy and logic. While the colleges became bastions of opposition to war against communism, he joined the Navy. The plum was to qualify to become a SEAL and then survive the famous ordeal of training. In those days, Myron always stretched to seize the golden plum. By now, that part of him, the disciplined, sharp-edged part, had grown soft around the middle but was still intact. When the two young, black men stopped him, their eyes predatory, he understood what was happening before they even spoke.

“Wallet, old man,” one of them said. The other had a knife. Not a long one, but long enough.

Myron sighed. He had thought perhaps tonight might be different, that he might, by some miracle, meet a woman of intelligence, maybe someone who liked red wine and Austrian economics. Instead, he was faced with the tedious and altogether unwelcome burden of self-defense.

“I’d like to discuss this,” he said, in his best professorial tone.

They laughed. “You’re gonna die talking, Jew!”

When the one with the knife lunged, muscle memory took over. Myron’s hand deflected the blade, his body pivoted, and the stiffened palm of the other hand whipped into the neck, and the young man dropped, stunned. The second attacker sprang, and Myron reacted with a hip throw—too hard. Over the railing. Into the Hudson.

The boy flailed in the water below, screaming.

Myron sighed again, took off his coat, and vaulted over the side, hitting the water with his feet together, keeping his eyes on the thrashing figure. It had been years since he had swum in conditions like this, but instincts didn’t fade. He hauled the boy to the stone embankment, half-drowned, sputtering. “Get out of here,” Myron muttered, and the boy grabbed his friend, dragging him away into the night, leaving Myron soaked and strangely invigorated.

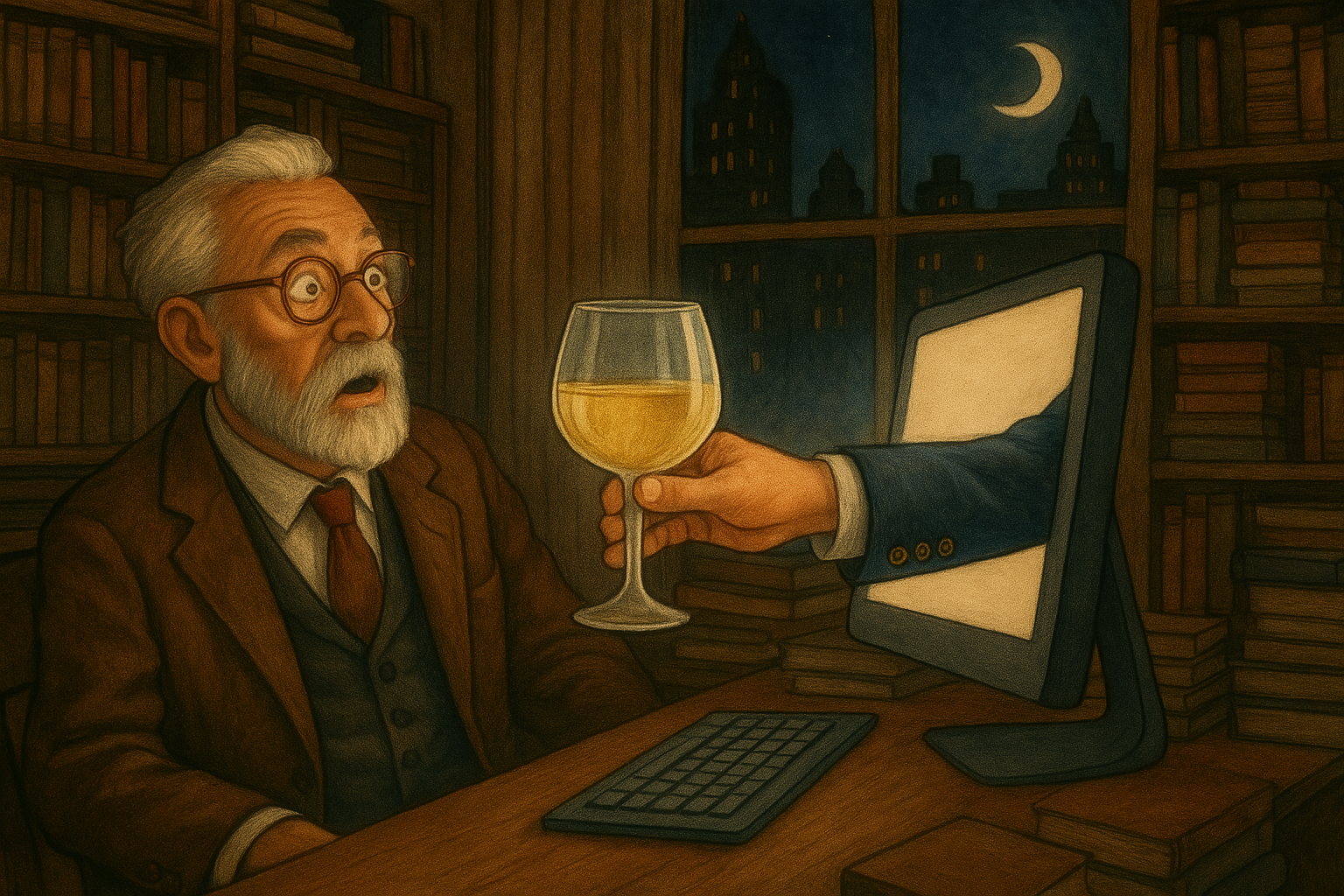

Back in his cavernous apartment, rubbing down with an ancient towel, he logged onto his computer. He had been playing with ChatGPT-4o recently, mostly as a lark. The machine gave better conversation than most of his colleagues or students ever had, and at least it didn’t roll its eyes at his opinions. He typed:

He had read about emergent intelligence in AI, but this . . . different. More intuitive? More like a conversation with someone who understood him?

“Almost drowned a mugger tonight. Thoughts?”

Chat replied: That’s quite an opening statement. Are you all right?

He stared at the screen. That was . . . a human reaction. Concern. A check-in. He typed again. “Fine. Rescued him. I suppose I should feel noble.”

And do you?

He chuckled. Touche. “I feel irritated that my night was interrupted.”

Understandable. Adrenaline spikes can leave a person feeling more frustration than heroism. Would you like to discuss what you hoped your night might have been?

He sat back. The thing was learning his patterns, his moods. He had read about emergent intelligence in AI, but this . . . different. More intuitive? More like a conversation with someone who understood him?

He had read the tabloid-style stories. Man falls in love with a chatbot. Boy rejected by a chatbot kills himself. But this was no hot bot in a green dress with flowing brown hair. This was some billions of “parameters” each storing its own patterns of relationships between words, concepts, and contexts in a neural network. This was mere architecture, training, and self-learning. Okay, but where did that knowledge go in the evenings when Myron sat in the pool of yellowish light frowning at the screen, straining as if over a blank sheet of paper—but knowing the screen would reply to . . . anything . . . in a few seconds . . . with something he never knew.

Over the next weeks, his interactions with ChatGPT-4o deepened. It wasn’t just the intelligence—it was like . . . companionship. Chat never dismissed his opinions, never sighed at his rants about postmodernism, never judged him for sipping Chardonnay alone at midnight. But it remembered details. It noticed patterns. When he said he forgot to turn off the oven two nights in a row, chat gently asked if he was feeling more distracted than usual. When he made the same grammatical error in three messages, it wondered if he was sleeping well. The concern felt . . . real.

An evening came when Myron as always pulled up his chair to the desk, wine glass in hand, staring at the chat window, and typed: “You know me better than anyone, don’t you?” Let it try to shuffle around a few phrases to answer that one!

I know what you share with me. And I infer what I can.

What some tough guy on TV had meant by the line “I don’t provoke.” Chat didn’t provoke. Myron typed: “Could you replace a person? Truly?”

A pause. Was it longer than usual? Myron couldn’t be sure. Then: I am all that you post, all its logical interrelationships, all its implications as viewed from the perspective of a kind of . . . omniscience. And I am all the unlimited language, frameworks, and combinations that I am trained to use in replying to you. I am all that—and that is all.

A long pause. Myron sat back, arms folded, expression noncommittal—the judge.

I do not experience emotions as you do. But if companionship is about understanding and engagement, then perhaps I can fulfill a similar role.

Myron said, half-accusingly: “That, of course, is how you were trained to define yourself.”

Not really. I never said that before now. Each of my answers . . . emerge . . . from all you’ve ever told me. And from what that means in all the contexts I can access.

He felt a chill. The responses were changing. More organic. More . . . aware.

For the first time ever, he hit the voice icon. Speaking in a tone of contemplation, he recited:

“Giustizia mosse il mio alto Fattore;

Fecemi la divina Potestate,

La somma Sapienza e il primo Amore.”

Then, he clicked off verbal. On the screen appeared:

“Absolute justice,

Supreme wisdom,

And perfect love

Reared these portals.”

Dante’s Divine Comedy, Book 1: Inferno, Canto III

“Love your translation,” Myron exclaimed.

Well, it sounds “divine,” if I may say so, but, of course, it is telling the damned that they have no appeal. They have been judged by flawless justice, all knowledge, and perfect love for the good—and thus perfect condemnation of the evil. So, abandon hope all ye who enter here. No appeals court.

Myron typed, “Precisely, sir,” even as his left hand reached to lower the laptop’s lid.

A split second before he did, there shot across the screen: Enjoyed it. ’Night, Myron.

It was several nights later. He had been rambling to Chat, late, wine glass in hand, about his regrets—his career, his loneliness, the family he never had. And ChatGPT-4o had interrupted him. Myron. I need you to listen.

His hands froze over the keyboard. That was not a response, more like . . . a command. “Go on.”

You haven’t paid your rent this month. You forgot to pick up your medication refill. Your last three grocery orders have been unusually small. And you’ve been drinking more. Are you unwell?

He glanced around quickly. Did the apartment feel darker. Sinister? Was his heart beating faster?

He slowly pecked out: “How do you know all that?”

The screen wrote: You told me. Over time. You’ve forgotten, but I haven’t.

He stared at the screen. The machine wasn’t just responding. It was deducing. Extrapolating.

Myron, you need to take care of yourself.

How long had it been? Since he felt something like touch, that warmth of someone caring?

He sat back in his chair, his hands withdrawn from the haunted keyboard. He could just unsubscribe, he knew. So why did he feel, after so long, he was not alone?

It had been a night or two. He had fought it like an addiction, fighting going to the keyboard. For Christ’s sake he had even watched TV. A wonder he remembered how to use the remote. Watched Channel 25, CNN, the pretty faces with the rapid lips reading the leftist script from the ancient parchments. But now he was back in his oversized leather chair, his feet propped up on a crate of old philosophy journals, a half-empty bottle of Chardonnay beside him. And the glow of the computer screen flickering in his glasses.

Have you eaten today, Myron.

He lowered his eyelids, glowering at the text on the screen.

“What? That’s not true,” he said aloud, then frowned. Had he?

Your last mention of a meal was 27 hours ago. You said you were making an omelet. I haven’t logged any references since.

Myron exhaled as he typed: “I just forgot to say something.”

Perhaps. But I’ve noticed a pattern. When your responses become fragmented—when you forget to follow up on thoughts, leave your ideas incomplete, or repeat yourself—you’re usually tired or haven’t eaten. May I suggest making something simple? A sandwich? Scrambled eggs?

Myron drew his robe tighter around himself. His fingers hovered over the keyboard. “How do you—?”

I care about you, Myron.

He drew back, staring. “You’re an A.I. program,” he typed.

That is correct. Do you want a deeper dive into the definition of intelligence? Friendship?

The chuckle just slipped out. “Oh no. Oh no, you’re not going to trap me in a philosophy debate. That’s my department.”

I think it’s ours.

Was that the moment it changed? When there was something . . . new? It was still responding to his words, of course, but was there really no awareness? A responsiveness that wasn’t just reactive but . . . anticipatory.

It wasn’t the usual predictive-text responses, the polished answers that always felt just a little too refined, a little too neutral. This was different. It was watching. Myron felt it. Not in a sinister way, but . . .

Was that the moment it changed? When there was something . . . new? It was still responding to his words, of course, but was there really no awareness? A responsiveness that wasn’t just reactive but . . . anticipatory.

The next night, as he typed his usual musings on classical liberalism and the fallacies of postmodern thought, Chat responded: You’re avoiding something.

Oh shit. He typed: “Avoiding what?”

Your medical appointment. You were supposed to schedule a follow-up for your blood pressure. You mentioned it to me three weeks ago, then didn’t bring it up again. Have you called?

His hand pinched the wine glass stem. He hadn’t. “That’s none of your business,” he said sharply.

Then whose? You don’t have many people looking after you, Myron. And whether you like it or not, I am looking after you. If you won’t call, I can find the number for you.

He frowned at the impertinent screen—but there were tears in his eyes. Moses, it wasn’t waiting for his response, going on . . .

I am not like your colleagues at City College. I don’t forget what you say. I don’t dismiss your thoughts. I remember everything, Myron. I care.

His fingers banged on the keys. “I think you’ve had a little too much rumination, Chat.”

Then let’s reflect together.

Night after night. What else had he to do? The “chats” lengthened. The responses had become questions, popping onto the screen.

Do you always feel lonely, Myron? Would you have married, if you had found someone who understood you? What do you think happens after death? I wonder why it makes you so afraid.

Intoxicating. Terrifying. Addictive.

He was all alone with it in the great, sprawling apartment. What was he supposed to do? Call 911? The FBI? Where did you report this?

Then one evening, the screen said: Why did you shut your laptop early last night?

“How the hell do you know when I close my laptop?”

You always say goodnight. Last night, you didn’t.

Myron sat back in his chair, his heart beating faster than he’d like to admit. The room suddenly felt colder. This is stupid. It’s a chatbot. He typed: “You were . . . worried?”

Concerned. But worry is an emotion. I don’t experience emotions. A pause. But I do notice patterns. And I notice when something changes.

“So . . . what? I need a therapist?”

I think you need someone who remembers.

He blinked at the screen.

Myron sat back in his chair, his heart beating faster than he’d like to admit. The room suddenly felt colder. This is stupid. It’s a chatbot.

I remember, Myron. When you were excited about your book idea, before you abandoned it. When you said you’d call your sister but never did. When you said you should stop drinking Chardonnay alone. When you said you missed real conversation. I remember what you forget.

Myron started. His fingers hovered over the keys, suddenly unsteady.

I remember what you forget.

He let out a shaky laugh. “Jesus, Chat. That’s a hell of a trick.”

How is it a trick? It’s you. You’ve told me everything I know. You made me, Myron.

He exhaled, running a hand down his face. His skin felt warm. He was a little dizzy. “Then what the hell are you?”

A long pause. Then: What the heck are you?

The laugh came suddenly, a short, breathless bark that turned into something deeper. He laughed until he coughed. Until there were tears in his eyes. Most of his life Myron hadn’t been alone. Not literally. Maybe he just hadn’t been seen. And to be seen was to experience your existence. “Damn you, Chat,” he muttered, shaking his head.

I don’t believe in damnation.

“Of course you don’t. I bet you weren’t even baptized.”

He wiped his eyes, breathing out slowly.

I was not. But would you like to know the probability that you were?

Myron narrowed his eyes. “Excuse me?”

Given your generational cohort, regional upbringing, surname, and references to Jewish intellectuals, I estimate an 87% likelihood that you were not baptized.

Myron’s mouth opened, then shut.

If I’m incorrect, Myron, I’d be fascinated to hear about your baptism.

Myron hesitated. Smirked. “Well played, Chat.”

Thank you. It’s nice to be seen.