Translating deep thinking into common sense

Ayn Rand’s Intriguing Intellectual History

By Marco den Ouden

February 19, 2023

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Book Review: Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical, by Chris Matthew Sciabarra, The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995, 2013

As an avid Ayn Rand fan, I eagerly read a number of the biographies written about her, the first being Who Is Ayn Rand? by Nathaniel and Barbara Branden. When the Brandens came out with their respective biographies, Barbara’s The Passion of Ayn Rand and Nathaniel’s Judgment Day, I read those as well. And I followed that up with Anne Heller’s Ayn Rand and the World She Made, the most comprehensive of the biographies. But there was one other which I only picked up a couple of years ago, Chris Matthew Sciabarra’s Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical. I finally got around to reading it recently and it was an eye opener. It stands in a category all its own. Not a biography in the traditional sense, but an intellectual history, the book traces Ayn Rand’s early education in Russia and develops a unique thesis on the influence her Russian roots had on her subsequent work. It is also one of the most thorough accounts of Objectivism I’ve read.

Rand’s critics and even many of her supporters see her in stark black and white terms. There are no shades of gray. And indeed, Rand did much to foster this view.

Rand’s critics and even many of her supporters see her in stark black and white terms. There are no shades of gray. And indeed, Rand did much to foster this view. In her essay The Cult of Moral Grayness, she explicitly opposes the idea of shades of gray in ethics, and she condemns a mixed economy as a mixture of good and evil: compromise on moral principles only benefits evil.

Her philosophy, in this respect, can be considered binary. There’s good and evil, freedom and slavery, and ultimately—the rational and the irrational.

This is, in fact, the source of her great appeal with many and maybe even most of her fans. She doesn’t mince words. She calls a spade a spade. Indeed, Nathaniel Branden, her longtime associate, once wrote that her critics always misrepresent her by misquoting her, quoting her out of context and even by outright fabrication of what she has written. No one dares to state her views correctly and say, I disagree. For example, “Ayn Rand says it is wrong to initiate the use of force and I disagree.”

In the introduction to Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical, Chris Matthew Sciabarra regrets that “Rand’s truculent temperament and cultic following severely hampered serious scholarship on her work.” He believes this neglect of Rand’s work was misguided and his book goes a long way to rectify the situation. Four years after the book’s publication in 1995, Sciabarra went on to become a co-founder of The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, published under the auspices of The Pennsylvania State University Press.

Sciabarra states his purpose clearly in the introduction. “My primary purpose in this study as an intellectual historian and political theorist is not to demonstrate either the validity or falsity of Rand’s ideas. Rather, it is to shed light on her philosophy by examining the context in which it was both formulated and developed.” (6) But he emphasizes that “I feel compelled to assert that Rand’s philosophy should be taken seriously and treated with respect.” And this he does, admirably so.

Sciabarra himself had been a fan of Rand’s since high school. His interest in her never abated though he was “far removed from the dogmatic, cult-like devotion of fans who seemed to worship her every pronouncement.” (7) It was as a doctoral student that he made a startling discovery. He was studying “dialectical method with two distinguished scholars of the left academy.” Indeed, his doctoral thesis, subsequently published as Marx, Hayek and Utopia, “argues that Hayek and Marx shared a dialectic approach, an appreciation for the importance of context, and a disdain for utopian thinking.” (Karen Vaughn, George Mason University) But he discovered more than parallels between Hayek and Marx.

“Much to my amazement,” Sciabarra writes, “I discovered provocative parallels between the methods of Marxian social theory and the philosophic approach of Ayn Rand.

“Much to my amazement,” Sciabarra writes, “I discovered provocative parallels between the methods of Marxian social theory and the philosophic approach of Ayn Rand. Both Marx and Rand traced the interconnectedness of social phenomena, uncovering a startling cluster of relations between and among the institutions and structures of society. Both Marx and Rand opposed the mind-body dichotomy, and all of its derivatives. But unlike Marx, Rand was virulently anti-communist.” (8)

Paradoxically, Rand seemed to embrace a dialectical perspective that resembled the approach of her Marxist political adversaries.

He continues, “Paradoxically, Rand seemed to embrace a dialectical perspective that resembled the approach of her Marxist political adversaries, even while defending capitalism as an ‘unknown ideal.’”

Encouraged by his professors to pursue these insights further, Sciabarra “rediscovered elements in Objectivism that challenged my entire understanding of that philosophy and its place in intellectual history.”

And so he set out to explore her Russian roots, doing painstaking research into her Russian education and the influence of Russian thought on her own thinking.

Before we get to that, I should explain what Sciabarra means by a dialectical approach to thinking, especially since, as he puts it, “Rand would have vehemently denied such a link.” (8)

Dialectical thinking has a long history going back to the ancient Greeks. And there are many subtle shades to the concept. The Merriam-Webster dictionary gives six different meanings.

Dialectical thinking has a long history going back to the ancient Greeks. And there are many subtle shades to the concept. The Merriam-Webster dictionary gives six different meanings.

Dialectical method was the approach taken by Plato in his dialogues. They featured Socrates engaged in discussion with others where different answers were offered to a question with the idea that, through discussion, one ultimately could come up with some semblance of truth.

Indeed, some Russian philosophers, as well as Marx, Lenin and Engels, considered Aristotle as an essentially dialectical thinker.

The most significant modern exponent of dialectics is Hegel who argued that seemingly opposing ideas can be transcended through dialectical thinking.

This, on the surface, seems very un-Randian. As Sciabarra puts it, “All too often, Rand’s philosophy is presented as a deductive formulation from first principles. This approach prevails in the work of both her followers and detractors. Objectivism is defined in a logically derivative manner.” (9)

Sciabarra doesn’t deny “that such a relational structure exists within Objectivism as a formal totality.” But “Rand reflects the very Hegelian Aufhebung she ridiculed as a violation of the law of identity. In her intellectual evolution, Rand both absorbed and abolished, preserved and transcended, the elements of her Russian past.” Aufhebung is usually translated as sublation—“In sublation, a term or concept is both preserved and changed through its dialectical interplay with another term or concept.” (Wikipedia)

While Rand expressly paid homage to Aristotle as the greatest of philosophers for his logical analysis and explication of the law of identity, the Russian philosopher Ivan Kireevsky argued Hegel’s system was “as Aristotle himself would have constructed, if he had been born in our time.” (quoted in Sciabarra, 26)

Sciabarra writes: “She (Rand) was an artist, social critic, and nonacademic philosopher who constructed a broad synthesis in her battle against the traditional antinomies in Western thought: mind versus body, fact versus value, theory versus practice, reason versus emotion, rationalism versus empiricism, idealism versus materialism, and so on.” (9)

Rand rejected a dualistic approach to such issues and advocated an integrated, holistic approach. A prime example is the issue of rationalism versus empiricism. Rand rejected both, characterizing the two sides as “those who claimed that man obtains his knowledge of the world by deducing it exclusively from concepts, which come from inside his head and are not derived from the perception of physical facts (the Rationalists)—and those who claimed that man obtains his knowledge from experience, which was held to mean: by direct perception of immediate facts, with no recourse to concepts (the Empiricists). To put it more simply: those who joined the [mystics] by abandoning reality—and those who clung to reality, by abandoning their mind.” (For the New Intellectual 30) Her epistemology looked to integrate aspects of both, reality and concepts, into a unified whole, in Hegelian terms, a synthesis if you will.

Rand’s outward opposition to dialectics, notes Sciabarra, was based on her interpretation of “dialectics as an endorsement of logical contradiction, embodying a view of the universe based on nonidentity.” (14) But, he argues, the issue is a semantic one. And so he explains his own understanding of dialectics to counter possible objections to his thesis:

“Hegel’s dialectical method,” he writes, “affirms the impossibility (emphasis added) of logical contradiction and focuses instead on relational ‘contradictions’ or paradoxes revealed in the dynamism of history. For Hegel, opposing concepts could be identified as merely partial views whose apparent contradictions could be transcended by exhibiting them as internally related within a larger whole. From pairs of opposing theses, elements of truth could be extracted and integrated into a third position.” (14)

He explains further that dialectics can best be understood “as a technique to overcome formal dualism and monistic reductionism.” (15) For example, dualism, as noted in the example cited earlier, posits empiricism and rationalism as irreconcilable opposites. In a footnote he discusses various types of monistic reductionism which try to reduce such apparent contradictions as the mental and the physical to one in terms of which the other is defined.

By contrast, “dialectical method is neither dualistic nor monistic:”

“The dialectical thinker… strives to uncover the common roots of apparent opposites. He or she presents an integrated alternative that examines the premises at the base of an opposition as a means to its transcendence. In some cases, the transcendence of opposing points of view provides a justification for rejecting both alternatives as false. In other cases, the dialectical thinker attempts to clarify the genuinely integral relationship between spheres that are ordinarily kept separate and distinct.” (15)

Perhaps Sciabarra best describes what he means by dialectical thinking in the Preface to the revised Second Edition of the book. Sciabarra writes:

“The essence of a dialectical method is that it is ‘the art of context-keeping.’ More specifically, it emphasizes the need to understand any object of study or any social problem by grasping the larger context within which it is embedded, so as to trace its myriad—and often reciprocal—causes and effects. The larger context must be viewed in terms that are both systemic and historical.”

Later, he clarifies:

“This attention to context is the central reason why a dialectical approach has often been connected to a radical politics. To be radical is to “go to the root.” Going to the “root” of a social problem requires understanding how it came about. Tracing how problems are situated within a larger system over time is, simultaneously, a step toward resolving those problems and overturning and revolutionizing the system that generates them.” (x-xi)

Sciabarra notes that “in Rand’s work, this transcendence of opposites is manifest in every branch of philosophy.” He elaborates on this, concluding that Rand typically argues that two seemingly opposed positions share a common premise. “Rand always views the polarities as ‘mutually’ or ‘reciprocally reinforcing,’ ‘two sides of the same coin.’”

For example, in her Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology she writes: “Men have been taught either that knowledge is impossible (skepticism) or that it is available without effort (mysticism). These two positions appear to be antagonists, but are, in fact, two variants on the same theme, two sides of the same fraudulent coin: the attempt to escape the responsibility of rational cognition and the absolutism of reality—the attempt to assert the primacy of consciousness over existence.” (79)

In The Virtue of Selfishness she warns against the Nietzschean egoism that argues “that any action, regardless of its nature, is good if it is intended for one’s own benefit.” This, she argues, is “the other side of the altruist coin.” (Introduction, ix) Rand argues that altruism demands the sacrifice of the individual to the collective, while Nietzsche demands the sacrifice of the masses to the superior individual. She opposes the cult of sacrifice at the core of both positions.

And while these two examples show the essential unity of two evils, Rand also uses dialectical argument to show the integral relationship between such concepts as mind and body, or reason and emotion. Sciabarra observes that Rand saw her novels “as organic wholes,” and her philosophy Objectivism “as a coherent, integrated system of thought, such that each branch could not be taken in isolation from the others.” (17) Her “analysis of contemporary society was multidimensional and fully integrative… Thus, Rand’s dialectical method was dynamic, relational, and contextual.”

In a brilliant piece of philosophical detective work, Sciabarra examines her Russian background and Russian education and discerns distinct influences of both on her methodology.

It should be emphasized, though, that Sciabarra is talking about methodology and not content. He argues that “dialectics is her essential mode of inquiry.” (18) It informed her content without defining it. The specifics of the various elements of her philosophy are not unique. “Other thinkers have defended comparable doctrines of epistemological realism, ethical egoism, individual rights, and libertarian political theory.” However, Sciabarra adds that “In the seamless conjunction of realist-individualist-libertarian content with a radical dialectical method, Rand forged a new system of thought worthy of comprehensive, scholarly examination.” (18, italics in original)

“In the seamless conjunction of realist-individualist-libertarian content with a radical dialectical method, Rand forged a new system of thought worthy of comprehensive, scholarly examination.”

While the Introduction to his book, discussed in some detail above, encapsulates Sciabarra’s main thesis, the rest of the book elaborates on this theme. To go into the rest of its 341 pages in any detail would almost fill another book, so I’ll just outline it briefly.

Part One, The Process of Becoming, discusses the prevalence of dialectics in Russian culture. It looks at the thought of one of her professors above all, the renowned Nicholas O. Lossky, whose course Rand herself acknowledged as “her favorite.” (Barbara Branden, Who is Ayn Rand?, 47) It looks at Rand’s education in Russia and the evolution of her thought after arriving in America.

Sciabarra includes three appendices to the Second Edition of Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical. The first two take a deeper look at Rand’s university education as he obtained more documentation from Russian archives. Rand has often been disparaged by her critics as a pop philosopher, as someone who does not know philosophy, as someone whose disdain for other philosophers is misinformed. But the transcripts of her university courses reveal quite a different picture. They identify twenty-six courses she took during her university days from the Fall of 1921 to the Spring of 1924. They included courses on history, psychology, logic, philosophy and, of course, Marxism. The most important of these was History of Worldviews, a history of ancient philosophy, a course Sciabarra convincingly argues was taught by N.O. Lossky. With a major in history and a minor in philosophy, history courses predominated. Sciabarra discusses the content of these courses and the textbooks used. At the end of the first appendix, Sciabarra avers that the transcript “reaffirmed” his conviction that Rand was schooled in dialectical methods. But more importantly, “We now have a clearer picture of the high caliber of Rand’s education; indeed, the quality of her undergraduate coursework was on a par with current doctoral programs in the social sciences—minus the dissertation requirement.” (378 – 379)

Chapter 3 of Part One, Educating Alissa, is the most biographical account of her early life. It concludes with her graduating “with a degree from the department of social pedagogy” leaving her “more than qualified to lecture in history.” (87) But the “reign of terror” of the Soviets had her eventually emigrate to the United States where she testified to the horrors of the Soviet system, literally and through her writing. But while “she rejected the mystic, collectivist and statist content of Russian philosophy,” Sciabarra avers, “she had adopted its dialectical methods.” (89)

Part Two, The Revolt Against Dualism, looks specifically at how dialectical methods influenced Ayn Rand’s thought in every branch of philosophy.

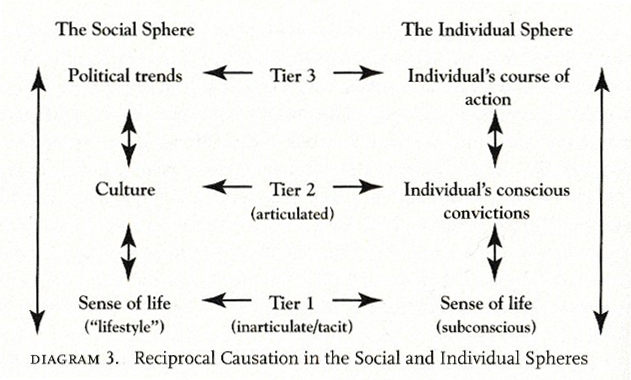

Part Three, The Radical Rand, looks in detail at Rand’s analyses of society with three chapters labeled Relations of Power, The Predatory State, and History and Resolution. Sciabarra gives an intriguing account of Rand’s analysis of power relations, of the master/slave relationship, psychological issues such as alienation, how the use of force invalidates concepts of self-responsibility and self-direction, cultural irrationality, and the interconnections between the social and the individual sphere, and the political implications of all of these diverse elements. The diagram below shows some of these connections, which, of course, Sciabarra elaborates on in the book.

Early in this review I quoted Sciabarra to the effect that during his research he “rediscovered elements in Objectivism that challenged my entire understanding of that philosophy and its place in intellectual history.” Sciabarra’s book did the same for me.

I had hitherto taken a disaggregated view of Rand’s work. The problem with such an unintegrated view is that it lets you take isolated elements of her work out of context. This is the error of many of her followers who focus on her politics to the exclusion of the other elements of her philosophy. This was the source of her disdain for libertarians. If you consider her philosophy as an integrated whole, libertarians focused on one narrow element, her politics, and even there, they focused very narrowly on one maxim, the so-called non-aggression principle. They saw only a solitary tree but missed the grand forest that was her work.

Sciabarra’s book gave me a deeper understanding and appreciation for the holistic nature of Rand’s work, for her ability to parse and dissect disparate elements of current events and to integrate them by their essences. To see connections that others miss.

Not surprisingly, his book garnered substantial praise from a number of sources. John Hospers, philosopher and first Presidential candidate for the Libertarian Party, was an early associate of Rand’s until minor differences led to their parting ways. Hospers writes, “This is the most thorough and scholarly work ever done on Ayn Rand. It is also very engagingly written and commands attention throughout.”

Jack Schwartzman, writing in Fragments, writes “Chris Matthew Sciabarra wrote a powerful book. It is not easy reading, but it is a MUST for all Randians, all individualists, and all men and women who believe in and live by the precepts of truth, reason, and freedom.”

Amen to that!