Translating deep thinking into common sense

Can Cultural Values Explain Authoritarianism?

By Winton Bates

August 5, 2023

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

The focus of this essay is whether it is appropriate to view the ideologies of political leaders who are opposed to liberty as a product of the cultural values of the people they govern. That is of interest because it has bearing on the extent of support people are likely to give to political movements favouring less constraints on personal and economic freedom. People who feel that the ideologies of political leaders are aligned with their personal values, are less likely to support change.

The following propositions are taken as given:

- Everywhere in the world, governments constrain liberty to some extent.

- The ideologies of political leaders have an important influence on the activities of governments. Even those political leaders who claim to be entirely pragmatic are taking an ideological position—they are expressing ideas, beliefs, and attitudes about their approach to public policy.

- Authoritarian governments enforce obedience to systems of regulation which severely restrict individual liberty.[i]

I begin by discussing the positioning of political leaders on a political compass.

The political compass

In 18th century France, where the left-right terminology originated, support for free markets and civil liberties came mainly from the left.

The positioning of political leaders on the conventional left-right political spectrum conveys ambiguous information about their attitudes toward individual liberty. In 18th century France, where the left-right terminology originated, support for free markets and civil liberties came mainly from the left. By the late 20th century, the right was more strongly associated with individual freedom, while the left was associated with pursuit of collectivist goals. Even then, however, those who identified with the political right included nationalists, social conservatives, and paternalists whose support for individual freedom seemed to be largely rhetorical.

Ideological positioning clearly requires consideration of more than one aspect of an individual’s views. Researchers have made several different attempts to add dimensions to the political spectrum. For present purposes, The Political Compass has the virtue of focusing specifically on two dimensions of liberty—economic freedom and personal freedom. The website, politicalcompass.org , seeks responses to 64 propositions to tell individuals about their own ideological positions.

The positioning of a person on a political compass incorporating both economic and personal freedom is more informative about attitudes to liberty than attempts to position them on a single dimension. From a personal perspective, The Political Compass seems to provide accurate results. It positions me in the quadrant favoring high economic and personal freedom, where I would expect a Neo-Aristotelian classical liberal to be placed.

Nevertheless, my endorsement of The Political Compass is qualified. I am uneasy about the absence of information on the website about who owns it and how the methodology was developed. More importantly, the labelling of the axes as Authoritarian – Libertarian and Left – Right is not ideal. To be considered a libertarian, in my view, it is necessary to advocate economic freedom as well as personal freedom.

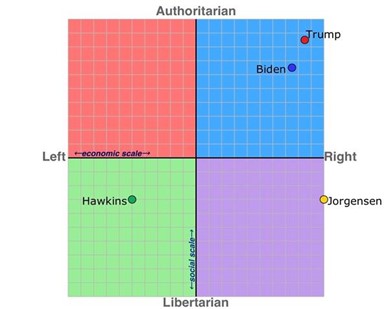

As I looked around the website, I noticed the chart (reproduced as Figure 1) which suggests that the main contenders in the U.S. 2020 election both held relatively authoritarian and right-wing views. The website shows similar ideological positioning for the main contenders in the Australian federal election held in 2022.

Figure 1: The 2020 US Presidential Election: Last Lap Reflections

Does that placement of the ideological position of political leaders make sense? The results presumably reflect the positions of the candidates on relevant issues at the time of the elections. The results make sense when I view them through the lens of the domestic politics of the countries concerned, particularly in the light of responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, but they make little sense in an international context. By international standards, the authoritarian tendencies of leaders of the major political parties seem to me to have been relatively mild in the U.S. prior to the 2020 election, and in Australia prior to the 2022 election. None of the policies that political leaders of these countries have advocated in recent elections would be likely to have much impact on the relatively high levels of personal and economic freedom that people enjoy in the U.S. and Australia.

If we want ideological labels that make sense according to international standards, we need an ideological map of the world rather than a domestic political compass.

An ideological map of the world

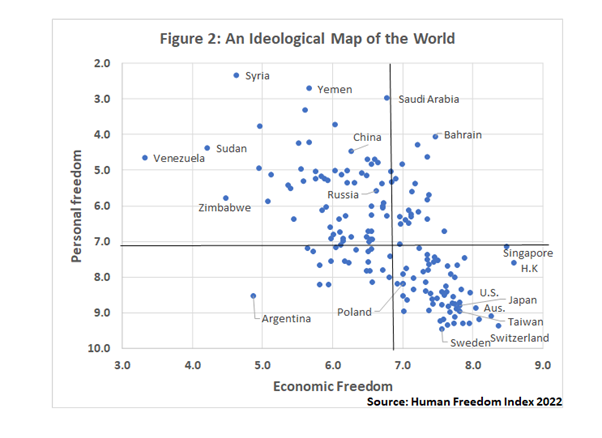

The results of the latest Human Freedom Index (Vásquez et al, 2022) can be used to illustrate differences in the prevailing ideologies of governments throughout the world. The Human Freedom Index, produced by the Fraser Institute and Cato, is the result of painstaking efforts to compile a vast amount of data relating to personal freedom and economic freedom in 165 countries.

The personal freedom index incorporates indicators of rule of law, security and safety, freedom of movement, freedom of religion, freedom of association and civil society, freedom of expression and information, and relationship freedom.

The economic freedom index incorporates indicators relating to size of government, legal systems and property rights, sound money, freedom of international trade and regulation.

Figure 2 indicates the relative position of different countries, with economic freedom shown on the x axis and personal freedom on the y axis. The values on the personal freedom axis are shown in reverse order (greater personal freedom at the bottom) to make it comparable to The Political Compass. The horizontal and vertical axes are positioned at median levels of economic and personal freedom.

The position of the U.S. and Australia is clear from the chart. The levels of both personal freedom and economic freedom in the U.S. are comparable to those of other liberal democracies, and far greater than in countries like China or Russia, which have authoritarian governments.

The position of the U.S. and Australia is clear from the chart. The levels of both personal freedom and economic freedom in the U.S. are comparable to those of other liberal democracies, and far greater than in countries like China or Russia, which have authoritarian governments.

It is unlikely that anyone with any knowledge of the political ideology of the governments of a range of different countries would be surprised by the correlation between economic and personal freedom they observe in the graph. They would also observe that countries with relative low levels of personal and economic freedom are ruled by authoritarian leaders who espouse ideologies that are opposed to liberty.

However, apologists for authoritarian leadership can point to evidence that in some countries with relatively low levels of personal and economic freedom a substantial proportion of the population profess to have “a great deal” of confidence in government. For example, data from the latest round of the World Values Survey (2017 – 2022) indicate that the percentage of people who have a great deal of confidence in the government is as high as 48% in China and 14% in Russia. The corresponding figures for the U.S. and Australia are 8% and 4% respectively.

The total percentages saying that they had “a great deal” and “quite a lot” of confidence in the government were 95% in China, 54% in Russia, 33% in the U.S. and 30% in Australia.

In my view, the best explanation for the high confidence that people profess to have in government in China and Russia is the combination of government propaganda and suppression of opposing political opinion.

I acknowledge, however, that the evidence of popular support for authoritarian governments would deserve to be taken seriously if it could be shown that the ideologies they follow are a product of the cultural values of the people they govern. In the following sections, I have attempted to test that proposition by examining the extent to which personal freedom and economic freedom ratings can be explained by cultural values in different countries.

Economists’ perspectives on cultural values

My understanding of cultural values is strongly influenced by several leading economists. Friedrich Hayek recognized the importance of cultural values when he observed: “Man is as much a rule-following animal as a purpose-seeking one” (Hayek, 1982, Vol. I, 11). He argued that norms of just conduct reflect the experience of generations and evolve gradually. Michael Jenson and William Meckling also recognized that customs and mores constrain human behavior but pointed out that many changes in social attitudes could be explained in terms of changes in benefits and costs to individuals of engaging in particular behaviors. For example, they argued that changes in sexual morality have been influenced by advances in birth control technology (Jenson and Meckling, 1994, 16).

Cultural values are ultimately a product of processes occurring in the minds of individuals.

Cultural values are ultimately a product of processes occurring in the minds of individuals. Frank Knight saw humans as beings who aspire not only to satisfy given desires but also to hold better preferences. James Buchanan built on that foundation in suggesting that individual humans have an artifactual nature because they have a wide area of choice in forging their own characters within the constraints imposed upon them by human nature. In a recent contribution, Paul Lewis and Malte Dold discuss the contributions of Knight and Buchanan, and suggest that social context should also be taken into account because it can facilitate or impede the efforts of an individual to become the kind of person he/she wants to become (Lewis and Dold, 2020). The approach to individual value formation developed by Lewis and Dold is similar in some respects to that of Gary Becker, which I have drawn upon to suggest that human flourishing is a multi-stage process, influenced by social capital—including the values of family and peer groups – as well as effective use of personal capital (Bates, 2021, 128 – 131).

Do emancipative values explain personal freedom levels?

The concept of emancipative values, developed by Christian Welzel, a political scientist, seems to me to be broadly consistent with the views of economists as outlined above. His central idea in that a desire for emancipation from external constraints is deeply rooted in human nature. It stems from the ability of humans to make conscious choices and to imagine a less constrained existence (Welzel, 2013, 121).

In constructing his emancipative values index, Welzel used data from the World Values Survey (WVS) covering the beliefs that individuals hold about such matters as the importance of personal autonomy, respect for the choices they make in their personal lives, having a say in community decisions, and equality of opportunity. Emancipative values remain relatively dormant when people are poor, illiterate, and isolated in local groups. In those circumstances, people tend to place lower value on freedom of choice and more equal opportunity than on meeting their most basic needs. Larger numbers of people have tended to adopt emancipative values in an increasing number of societies as economic development has proceeded. Emancipative values have strengthened substantially in many countries over only a few decades (Welzel, 2013, 336).

The strengthening of emancipative values is explained by growth of action resources (wealth, intellectual skills, and opportunities to connect with others) rather than civic entitlements such as voting rights. As emancipative values have strengthened, more people have come to recognize the value of civic entitlements and have used their growing material resources, intellectual skills, and opportunities to connect with others, to take collective action to achieve such entitlements. The process has been ongoing, with people showing greater concern for promoting more widespread opportunities—including greater opportunities for women, ethnic minorities and the disabled—as material living standards have risen and emancipative values have strengthened. (For further discussion of Welzel’s research on emancipative values, please see: Bates, 2014; and Bates, 2021, 184 – 190).

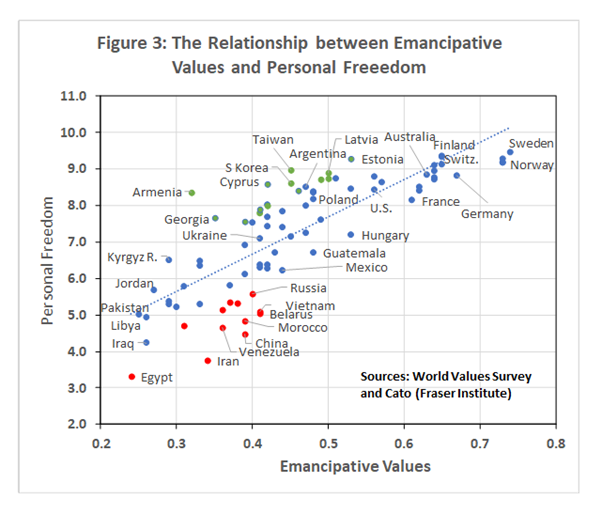

Figure 3 was constructed by matching data on emancipative values from the latest round of the WVS (2017 – 22) with the Fraser Institute’s data on levels of personal freedom for 2020. Matching of data was only possible for 85 of the 165 jurisdictions covered by the Fraser indexes.

The graph shows that personal freedom tends to be greatest in countries where people hold the most emancipative values. However, it also shows that in some countries personal freedom levels are substantially higher, or lower, than predicted on the basis of those values. The data points for those with personal freedom substantially higher than predicted are shown in green and for those substantially lower, in red. (For this purpose a substantial divergence is a level of freedom more than one point higher than, or lower than, the prediction shown by the linear regression line.)

The graph shows that personal freedom tends to be greatest in countries where people hold the most emancipative values. However, it also shows that in some countries personal freedom levels are substantially higher, or lower, than predicted on the basis of those values. The data points for those with personal freedom substantially higher than predicted are shown in green and for those substantially lower, in red. (For this purpose a substantial divergence is a level of freedom more than one point higher than, or lower than, the prediction shown by the linear regression line.)

It seems clear from the graph that the ideologies of many authoritarian governments cannot be fully explained in terms of the values held by the people they govern.

The pattern of green and red points is interesting. The countries in which personal freedom levels are substantially higher than predicted tend to have emancipative values in the middle range, whereas those with personal freedom substantially lower than predicted have emancipative values towards the bottom of the scale.

Looking now at individual countries, those with personal freedom substantially greater than predicted—for example, Armenia, Georgia, Cyprus and Taiwan—tend to have representative governments. Those with substantially less personal freedom than predicted—for example, Iran, China, Vietnam, Belarus and Russia—have authoritarian governments.

Is personal freedom less secure in countries if it is greater than prevailing values seem to support? If a high proportion of the population considers that existing policy regimes are not aligned with their personal values, these regimes could be expected to be relatively fragile, other things being equal. I have attempted to test that proposition by using WVS data from the 2010 – 14 to obtain predictions of personal freedom for 2012. It was possible to obtain matching data for 53 countries. The results provide some support for the proposition that personal freedom is not secure unless supported by emancipative values. Of the 6 countries in which personal freedom was much greater than predicted in 2012, only one had higher personal freedom in 2020, another had unchanged personal freedom, and the other 4 had lower personal freedom.

The same reasoning would suggest, other things equal, that relatively low levels of personal freedom are less likely to persist when prevailing values support greater freedom. Unfortunately, other things are not equal because authoritarian regimes suppress political opposition. Of the 6 countries in which personal freedom was much less than predicted in 2012, none had higher personal freedom in 2020, and 2 experienced a further decline in personal freedom.

Do facilitating values explain economic freedom levels?

There has been a substantial amount of previous research undertaken on determinants of economic freedom (Lawson et al, 2018) and on cultural values supporting economic growth and institutional change. (For a brief review, see: Moellman and Tarabar, 2022.) However, I am not aware of any previous attempt to explain economic freedom levels in terms of a facilitating values index similar to the one used here.

The facilitating values index used here is based on WVS data relating to individual autonomy and trust. The priority people place on individual autonomy seems likely to be important in facilitating economic freedom because respect for autonomy implies respect for individuals engaged in commerce, particularly innovators. Trust of strangers seems likely to be important in facilitating economic freedom because it reduces the tribal instinct to seek to use the powers of the state to advance the interests of group members at the expense of other groups.

I have used Christian Welzel’s autonomy index to measure autonomy. This index uses three items in the World Values Survey (WVS) which ask respondents their views about desirable child qualities. Autonomy is considered to be valued more highly by those who identify independence and imagination as desirable child qualities but do not consider obedience as such a quality (Welzel, 2013). The index data used is based on the latest round of the WVS (2017 – 2022).

Welzel’s generalized trust index was used to measure interpersonal trust. This index gives higher weight to trust of strangers than to trust of family and friends. The index was reconstructed for the latest round of the WVS by combining items covering close trust (trust of family, neighbours, and people you know personally), unspecified trust (whether most people can be trusted) and remote trust (trust of people you meet for the first time, people of another religion and people of another nationality). Unspecified trust was given double the weight of close trust, and remote trust was given three times the weight of close trust.

In constructing the facilitating values index, autonomy was allocated 75% of the weight and generalized trust was allocated 25%. Those weights were chosen on the basis of regression analysis using the autonomy and generalized trust indexes as explanatory variables to explain economic freedom.[ii]

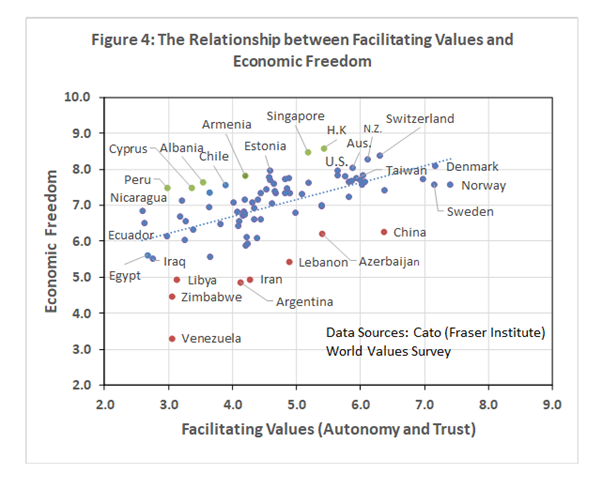

Figure 4 was constructed by matching data for the facilitating values index (available for 85 countries) with the Fraser Institute’s economic freedom data for 2020.

The graph suggests that values facilitating economic freedom help to explain why some countries have higher economic freedom than others. In many countries, however, prevailing government ideologies which either support or oppose free markets do not seem to be attributable to underlying facilitative values.

The graph suggests that values facilitating economic freedom help to explain why some countries have higher economic freedom than others. In many countries, however, prevailing government ideologies which either support or oppose free markets do not seem to be attributable to underlying facilitative values.

One of the things you may notice in the graph is that values facilitating economic freedom are shown to be higher in China than in the U.S. and Australia. It may seem surprising that individual autonomy is assessed to be relatively high in China in the light of Geert Hofstede’s analysis which suggests that Chinese people tend to have a collectivist orientation and are more inclined to act in group interests rather than personal interests. Support for the view that many Chinese people have an individualistic perception of human flourishing is provided in data in a blog article I wrote on that topic in 2021.

While you are thinking about China, you might like to compare economic freedom in that country with that in Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. The most obvious reason why the latter jurisdictions have greater economic freedom is because they have adopted market-friendly ideologies.

Similarly, adoption of market-friendly ideologies explains why Albania has substantially greater economic freedom than Iran and Libya, and why Chile has greater economic freedom than Argentina and Venezuela.

Is economic freedom less secure in countries in which it is higher than facilitating values seem to support? Only 3 jurisdictions were identified in which economic freedom in 2012 was greater than predicted on the basis of facilitating values at that time. In 2020, economic freedom was lower in one of those jurisdictions and about the same in the other 2.

It is more informative to look at the recent history of the 6 countries in which economic freedom in 2020 was substantially greater than predicted by facilitating values. Albania, Armenia, Cyprus and Peru have all maintained economic freedom ratings above 7 for over a decade. Hong Kong and Singapore have had relatively high economic freedom ratings over a longer period. I am not aware of any obvious reason to question the future of economic freedom in any of these jurisdictions, except perhaps Hong Kong. Since Hong Kong is a special administrative region of China the future of economic freedom in that jurisdiction will depend on the future policies adopted by a government which is ideologically opposed to economic freedom.

Unfortunately, available evidence does not provide grounds for optimism that a level of economic freedom that is lower than predicted by facilitating values will necessarily bring about reforms leading to higher economic freedom. Of the 6 countries in which economic freedom was substantially lower than predicted by facilitating values in 2012, levels of economic freedom declined further in 3 and remained about the same in the other 3.

Nevertheless, governments that are unresponsive to the aspirations of citizens are inherently fragile. When suppression of economic freedom leads to economic stagnation or decline, it can become increasingly difficult for an authoritarian leader to obtain the resources required to suppress political opposition. Over the longer term, it is possible to point to instances of regime change leading to greater economic freedom (e.g., in several countries of eastern Europe following the collapse of the USSR) as well as to instances of ongoing suppression of economic freedom (e.g., North Korea).

In considering likely future developments with regard to economic freedom it is useful to keep in mind the findings of research by Russell Sobel (2017). Sobel found that significant improvements in institutional quality typically unfold gradually over a period of 25 years, but institutional decline happens more rapidly. He also found no evidence that reforms were less durable if they occur rapidly.

A composite picture

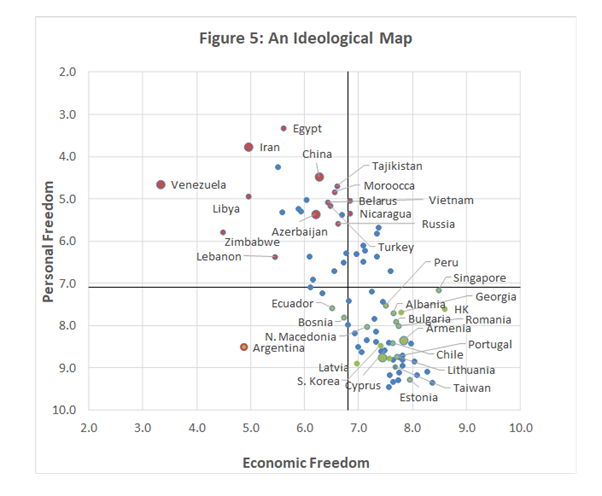

My answer to the question posed in the title of this article is apparent from Figure 5.

That graph differs from the ideological map of the world shown earlier (Figure 2) only in respect of the labelling of some of the data points and inclusion of only the 85 countries for which values data are available.[iii] I have attached country labels only to those data points which have freedom ratings that are substantially different from predictions based on emancipative and facilitating values. The colour of the labelled points depends on whether freedom is greater than or less than predicted—green if greater than predicted, red if less than predicted. The size of the labelled points is larger if both personal and economic freedom are greater than or less than predicted.

It is clear from Figure 5 that freedom ratings of most of the countries with low personal and economic freedom are substantially lower than predicted by emancipative and facilitating values. Suppression of liberty in those countries is a product of the ideologies of the governments rather than the cultural values of the peoples.

It is clear from Figure 5 that freedom ratings of most of the countries with low personal and economic freedom are substantially lower than predicted by emancipative and facilitating values. Suppression of liberty in those countries is a product of the ideologies of the governments rather than the cultural values of the peoples.

The graph also shows that a substantial number of countries with relatively high personal and economic freedom are performing better in that regard than can readily be explained on the basis of prevailing values. Most of the countries concerned are not high-income countries that come to mind when one thinks of countries with relatively high levels of economic and personal freedom. In general, the high freedom levels of the high-income countries are more readily explained in terms of facilitating and emancipative values.

The existence of countries in which freedom levels are substantially greater than predicted by facilitating and emancipative values suggests that government support for economic and personal freedom may precede or accompany the evolution of facilitating and emancipative values. As noted earlier, the transition to high levels of economic freedom often takes place over an extended period. As market-friendly economic reforms promote the growth of economic opportunities, this could be expected to lead to the gradual evolution of facilitating values supporting higher levels of economic freedom. The growth of economic opportunities could be expected to encourage people to place higher value on personal autonomy and to become more trusting of others.

Milton Friedman observed that economic freedom “promotes political freedom because it separates economic power from political power and in this way enables the one to offset the other” (Friedman, 1982, 9). As economic development proceeds, the evolution of emancipative values provides additional support for personal freedom.

The correlation between economic and personal freedom is strikingly evident in Figures 2 and 5. There are not many countries with relatively high personal freedom and low economic freedom, or vice versa. The current circumstances of Argentina—which stands out as the only country having high personal freedom despite low economic freedom—helps illustrate why that is so. In Argentina, the decline in economic freedom over the last 20 years has been accompanied by worsening economic prospects, which seem likely to lead, before long, to an economic and political crisis. Hopefully, the political response to the crisis will be to restore greater economic freedom and make personal freedom more secure, rather than to restrict personal freedom to suppress criticism of government policies.

Bahrain is a country that stands out as having relatively high economic freedom and low personal freedom levels (Figure 2). There are some grounds for optimism that future governments of Bahrain will have more regard for personal freedom, as had occurred in other countries that have been similarly placed in the past. For example, people in Chile and Taiwan have enjoyed relatively high personal freedom levels in recent decades, following earlier periods in which personal freedom was suppressed.

I do not want my adoption of an international perspective in this essay to leave readers with the impression that I see no reason for concern about the future of economic and personal freedom in the high-income liberal democracies. Despite the prevalence of facilitating and emancipative values in those countries, ideological trends within them now seem to me to pose a greater threat to liberty than at any time since the 1970s.

An observation that Ayn Rand made about the U.S. in the 1960s helps to make the point. Rand posed herself a question about the dominant ideological trend of culture at that time and concluded that a form of fascism—guild socialism—was becoming more apparent. She wrote:

“There is, however, one difference between the type of fascism towards which we are drifting, and the type that ravaged European countries: ours is not a militant kind of fascism, not an organized movement of shrill demagogues, bloody thugs, hysterical third-rate intellectuals, and juvenile delinquents—ours is a tired, worn, cynical fascism, fascism by default, not like a flaming disaster, but more like the quiet collapse of a lethargic body eaten by internal corruption” (Rand, 1967, 220).

When I first read that, during the 1980s, it seemed to me that a resurgence of free-market ideology had averted those fascist tendencies—at least in the US, UK, Australia, and New Zealand. Reading Rand’s contribution again now, it seems to me that those fascist tendencies have returned and are now more virulent than during the 1960s and 70s. Because of crony capitalism and woke progressivism, the economies of the high-income liberal democracies have become corporatist quagmires in which government intervention and expectations of future government intervention greatly hinder the ability of markets to weed out inefficient firms. Those tendencies have yet fully reflected in economic freedom levels. At the same time, personal freedom is threatened by an increasing tendency for “shrill demagogues,” among both conservatives and progressives, to resort to government coercion in conducting their culture wars.

Conclusions

In this essay I have adopted an international perspective to consider the extent to which cultural values explain authoritarianism. The analysis has been conducted in terms of ideological maps which position governments by reference to the levels of personal freedom and economic freedom in the countries they control.

The essay introduces the concept of international ideological mapping by first considering how individuals might assess their own ideological positions. I argue that the positioning of a person on a political compass, incorporating both economic and personal freedom, is more informative about attitudes to liberty than attempts to position them on a single dimension.

The Human Freedom Index provides data on economic freedom and personal freedom for a large number of countries. That data can be viewed as an ideological map of the world because it reflects the prevailing ideologies of governments throughout the world.

Ideological maps show high correlation between economic freedom and personal freedom.

Ideological maps show high correlation between economic freedom and personal freedom. The liberal democracies have relatively high levels of both economic and personal freedom. Authoritarian governments have relatively low levels of both personal and economic freedom.

I argue that the question of whether cultural values can explain authoritarianism is worth exploring because survey data shows that people in some countries with relatively low levels of economic and personal freedom (e.g., China and Russia) claim to have more confidence in their respective governments than do people in some countries with relatively high levels of personal and economic freedom (e.g., the U.S. and Australia).

Data from the World Values Survey was used to test the extent to which levels of personal and economic freedom could be explained by cultural values. Christian Welzel’s index of emancipative values was used to explain levels of personal freedom. and an index of facilitating values was constructed to explain levels of economic freedom.

The existence of emancipative values and values facilitating economic freedom does help to explain why some countries have higher personal and economic freedom than others. In general, the high freedom levels of the high-income liberal democracies are fairly well explained in terms of facilitating and emancipative values.

Suppression of liberty in those countries is a product of the ideologies of the governments rather than the cultural values of the peoples.

However, the ideologies of many other governments cannot be adequately explained in terms of the values held by the people they govern. The freedom ratings of most of the countries with low personal and economic freedom are substantially lower than predicted by emancipative and facilitating values. Suppression of liberty in those countries is a product of the ideologies of the governments rather than the cultural values of the peoples.

The analysis also shows that a substantial number of countries with relatively high personal and economic freedom are performing better in that regard than can readily be explained on the basis of prevailing values. One possible explanation is that market-friendly economic reforms tend to separate economic power from political power, enabling greater political freedom to emerge before it is fully supported by emancipative values.

References

Bates, Winton. (2014) ‘Where Are Emancipative Values Taking Us?’, Policy, 30 (2). https://www.cis.org.au/app/uploads/2015/04/images/stories/policy-magazine/2014-winter/30-2-14-bates-winton.pdf

Bates, Winton. (2021) Freedom, Progress, and Human Flourishing, Hamilton Books.

Friedman, Milton. (1982) Capitalism and Freedom, University of Chicago Press.

Hayek, Friedrich. (1982) Law, Legislation, and Liberty,

Hoftede, Geert: Insights, Country comparison tool: https://www.hoftede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool

Jenson, Michael, and William Meckling. (1994) ‘The Nature of Man’, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Vol 7, No 2.

Lawson, Robert and Murphy, Ryan and Powell, Benjamin (2018) The Determinants of Economic Freedom: A Survey. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3266641 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3266641

Lewis, Paul, and Malte Dodd. (2020) ‘James Buchanan on the Nature of Choice: ontology, artifactual man and the constitutional moment in political economy’, Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol 44.

Moellman, Nicholas and Danko Tarabar (2022) ‘Economic Freedom Reform: Does culture matter?’, Journal of Institutional Economics (2022), 18, 139 – 157.

Rand, Ayn. (1967) Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, New American Library.

Sobel, Russell. (2017) ‘The rise and decline of nations: The dynamic properties of institutional reform’. Journal of Institutional Economics, 13(3), 549 – 574.

Vásquez, Ian, Fred McMahon, Ryan Murphy, and Guillermina Sutter Schneider (2022) The Human Freedom Index 2022, Cato Institute and the Fraser Institute.

Welzel, Christian. (2013) Freedom Rising, Cambridge University Press.

World Values Survey: https://worldvaluessurvey.org/wvs.jsp

[i] This combines several different dictionary definitions.

[ii] Researchers seeking further information about the methodology used in this article are welcome to contact me.

[iii] The horizontal and vertical axes are positioned at the median levels of economic and personal freedom for the 165 jurisdictions covered by the Fraser indexes. The countries not covered by the WVS tend to have lower freedom ratings than those which are covered. The median ratings for the 85 countries represented in the graph is 7.2 for economic freedom and 7.6 for personal freedom.

Related Posts:

About the Author: Winton Bates

-

A Bill of Natural Rights for Australia

April 20, 2025

-

Affirmative Action for Intellectual Diversity?

April 14, 2025

-

“Deep Learning”—But Is It Conscious?

April 10, 2025

-

AI: Intimations of “Emergence”

April 10, 2025

-

The Neuroscience of Cringe: Why the Past Still Burns

April 6, 2025

-

The 2025 Election: Australia vs the Global Deep State

April 1, 2025

-

Why the Trump-Musk Tour of Fort Knox Matters

March 29, 2025

-

A Meeting of Minds

March 27, 2025

-

Abortion and the Minimum Wage Law

March 24, 2025

-

Federalism or Anti-Federalism—That is the Question

March 24, 2025