Translating deep thinking into common sense

David Kelley: A Journey of Conviction

By Vinay Kolhatkar

November 3, 2017

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

There are significant gaps [in Objectivism] in the theory of propositions, induction, and certainty; the ethics of families; and legal philosophy. Some of these issues are being addressed by scholars on both sides of the divide.

The Savvy Street’s Vinay Kolhatkar (VK) caught up with David Kelley (DK), the uncompromising philosopher, on the eve of his retirement from the organization he founded.

VK: Let me start by offering congratulations on receiving the lifetime achievement award at the Atlas Society Gala on October 10.

DK: Thank you.

VK: It is always most fascinating, to me at least, when a person stakes an entire career and most of his adult life on one strong conviction, as you did back in 1990.

Courage is inspirational, more so because the mythological happy ending does not always come to pass.

First up though, we want to understand David Kelley the person, before we intensify the lens on the specifics of the struggle by painting the man who formed an unflinching conviction, and why he is still fighting a valiant philosophical battle. So, if I may, I would rather begin a little earlier.

The Formative Years:

VK: What was it like, growing up in Shaker Heights, Ohio, in the fifties? Who were your childhood heroes?

DK: As a child, I had the usual heroes of that time: Davy Crockett, the Lone Ranger, and the like. As a teenager, I had baseball heroes with the Cleveland Indians; and some teachers and other adults (in addition to my parents) whom I looked up to. It wasn’t until I began reading Ayn Rand that I had a specifically intellectual hero.

I had embraced individualism as well as atheism. Happiness seemed to me the only goal that could be an end in itself. So I was ready for Rand’s message. But even from a short excerpt I could tell she was way, way, far ahead of me along this road.

VK: Do you recall being brought up with a specific moral code? At what age did you give up religious beliefs (if any) and what caused that?

DK: My parents were Presbyterians and we went to church most Sundays while I was growing up. We were not deeply religious in the way some evangelical Christians are. In terms of morality, my parents emphasized kindness and generosity, but not other doctrines such as faith or asceticism. I did go to a confirmation class at 13 or 14. The discussions about what Christianity means were actually a stimulus to thinking philosophically, and I began challenging what I had been taught.

Not long after—I think I was 15—that habit of challenge led me to the question of whether there is a God in the first place. I could think of two reasons I had heard: that the world must have had a creator—how else could it exist? And that there is such incredible order in the world that it must have been designed. (As I later learned, these are the cosmological argument and the argument from design.) Neither seemed convincing to me, and I could think of counter-arguments. Within a year or so I was a confirmed atheist.

I am a philosopher first, and an Objectivist second, and that’s the only honest way to be in this profession.

VK: When did you first encounter Rand’s writings? What was that like?

DK: I was a junior in high school. I went with a youth group at our church on a ski trip. In the evenings, the leader would have us discuss issues. One evening he passed out an excerpt from what he described as a controversial writer whose ideas were sharply at odds with Christianity. The writer was of course Ayn Rand; the excerpt was from Roark’s trial speech in The Fountainhead. By this time, I had embraced individualism as well as atheism. Happiness seemed to me the only goal that could be an end in itself. So I was ready for Rand’s message. But even from a short excerpt I could tell she was way, way, far ahead of me along this road. So I read The Fountainhead …

The Crossroads:

VK: Why did you choose not to pursue an academic career that you trained for?

DK: I did teach at Vassar College for ten years after completing grad school. I left when I didn’t get tenure. I had to decide whether to look for another academic job. I chose not to for various reasons: I would have been a candidate only for not-as-good colleges; I wasn’t learning any more from my students; and academia was starting down the road to political correctness. During those years of teaching, I had also been writing articles for non-academic publications like Barron’s (a finance & business magazine). So I decided to write for a living and continue Philosophy on my own.

But I am not that interested in defining the limits of, or the criteria of, who is or who isn’t an Objectivist. I want to do Objectivism. I want to advance the knowledge.

VK: What brought about your first encounter with Ayn Rand in person? What was she like, over the years you knew her?

DK: I met Rand through Leonard Peikoff. After grad school I moved to NYC and gradually got to know the people surrounding her. I took part in a seminar that Leonard taught, and Rand came to the final session. I saw her a few more times over the next seven years before she passed away, but never knew her well. My impression was in line with what Barbara Branden and others have written: intensely perceptive, often warm, very interested in young minds, temperamental at times.

Fifty Years of Philosophy:

VK: Besides Rand, which thinkers have influenced you? In what way have they done so?

DK: I would mention Aristotle and John Locke, of course. But it’s hard to pick out specific thinkers. I’ve learned things from the many thinkers I’ve read, and on any issue I’m working on there are usually a number of writers whom I learn from.

VK: You arrived at Brown as a freshman in the fall of 1967. That’s fifty years in philosophy. What’s changed in the field over the years, for better or worse?

DK: When I was in undergraduate and graduate school (1967-75), there was a pretty sharp divide between analytic Philosophy (Anglo-American) and Continental (the rest of Europe). My schools were heavily analytic, but within ten years or so that dichotomy was being challenged, and philosophers were beginning to cross the divide—including my graduate advisor Richard Rorty.

Analytic Philosophy in my day was centered on language. The core focus of Objectivist philosophy, concepts, was widely regarded as an issue for cognitive psychology, not philosophy. That has changed as more philosophers get involved with cognitive science.

VK: But what is academic philosophy’s core today? Apart from defending against a Kantian reality-is-unknowable assault on epistemology, what protects this core from the increasing specializations and advances (even benevolent ones) in neuroscience, genetics, and physics which define the world around and inside us (the metaphysics of our world), positive psychology as a new & growing field for eudemonist ethics, law and politics (addressing jurisprudence & political science), and literature studies & aesthetics all as separate disciplines?

Or, is this, the so-called Philosophy’s King Lear problem, not a problem at all, because the philosopher is the quintessential integrator across the humanities and the natural sciences, the one that holds it all together?

DK: It’s true that issues once considered to be philosophical have been increasingly taken over by new fields like physics, psychology, biology, economics and so forth. That’s good because the development of those scientific methods allows us to test ideas in a more rigorous way than is possible in the philosopher’s armchair. But, at the same time, all the methods of the sciences–and the fundamental assumptions about causality, reason, evidence, and certainty–are philosophical at root.

So philosophy will always remain the examiner of fundamental premises. In fact, this whole trend over history has helped clarify and refine the role of philosophy as the study of fundamental principles underlying other fields. That’s true of descriptive fields like epistemology and metaphysics but it’s especially true of normative fields, e.g. in ethics. Psychological findings can be relevant to moral standards, but those standards are ultimately grounded in normative principles that belong to philosophy, not psychology. Another illustration is in the philosophy of law, where the best scholars are highly knowledgeable about law, but at some point you have to get to, if not start with, questions that are philosophical: What is a good society? What are people’s rights? These are not issues of legal theory or even of legal history.

There has also been a lot more interdisciplinary work, in my judgment, since my time in school. The illustration I know best is Cognitive Science; I was part of the Cognitive Science program at Vassar College, which I helped start—where we wanted a philosopher, a neuroscientist, a cognitive psychologist, and an AI researcher. We appreciated we had different perspectives and that we had something to learn from each other.

I see this happening all across philosophy now, not only in Cognitive Science, which is becoming a huge industry academically, but even in the philosophy of science.

VK: Speaking of philosophy’s core: epistemology, did you, or any Aristotelian philosopher, get involved in the Science Wars in the 90s, backing the scientists against the postmodernists and defending what was the proper framework for a philosophy of science? Your doctoral dissertation supervisor, Richard Rorty, writing about it in The Atlantic, failed to condemn the postmodernist vision.

DK: In the ‘90s, I was working at The Atlas Society (then the Institute for Objectivist Studies). I lectured and wrote a few pieces for our readers about objectivity in science, but didn’t write anything in academic journals. In the Evidence of the Senses, however, I did deal with issues in philosophy of science that related to perception—e.g., the claim that perception is “theory-laden.”

VK: To normal, rational, intelligent people, the extraordinary efficacy of the natural sciences seems obvious. We feel like saying to the philosopher who says “This brick wall does not in fact exist,”—“If you bang your head against the wall, you will soon find out that it does.”

DK: (Laughs.)

Thankfully, I have not heard Feyerabend’s name mentioned in a long, long time. But we do now have the postmoderns who are in effect sounding the same themes. But I don’t think most philosophers take that seriously.

VK: We, the people outside this academic ivory tower who are not epistemologists, are amazed that “epistemological anarchism” is taken seriously in our universities, e.g. the Feyerabend ideas that “scientific assumptions and conclusions should be supervised by committees of lay people,” and that “negative opinions about astrology and the effectiveness of rain dances were not justified by scientific research.” All that sounds like a horror movie to us. Is it that bad?

DK: I have read a lot of Feyerabend. In my day, he and Thomas Kuhn raised a lot of questions about the objectivity of science. They were like the precursors to the postmodernist trend.

Thankfully, I have not heard Feyerabend’s name mentioned in a long, long time. But we do now have the postmoderns who are in effect sounding the same themes. But I don’t think most philosophers take that seriously. I have not been to academic conferences for a long time but my sense is that most philosophers have more sense than that.

The Split:

VK: Was the commencing of The Institute for Objectivist Studies your idea? Did others help you form it, and invite defectors to what was once termed a “Home for Homeless Objectivists?”

VK: Was the commencing of The Institute for Objectivist Studies your idea? Did others help you form it, and invite defectors to what was once termed a “Home for Homeless Objectivists?”

DK: Several people worked together in making plans: Walter Donway, Murray Franck, Molly Sechrest, and Bob Patterson. But it was mainly my decision to go forward, since I was the one who conceived of open Objectivism; I was the flash point for the controversy; and I was the only one with time to run the organization.

VK: Was there a single incident that led to your leaving ARI (e.g. interacting with libertarians, or the refusal to denounce Barbara Branden) or, looking back, was your departure inevitable in view of the fundamental disagreements?

DK: There were several issues and incidents over about three years, including the ones you mention. And during this time I was trying to understand the differences among Objectivists that had come to the surface, and I began to expect there would be an explosion at some point. Peter Schwartz’s attack on me for speaking to libertarians was the final spark.

The Conviction in Practice:

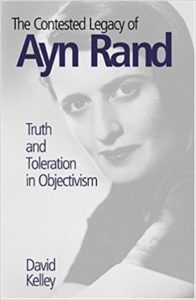

VK: In the 1990 Truth and Toleration monograph, you stated that (a) it’s a mammoth task to delineate precisely what is distinctive about Objectivism relative to other philosophies and (b) to lay down standards for adding to the system. You formed an outline back then of the foundations of such an exercise. What’s the state today, in 2017, of documenting further the distinctiveness of Objectivism and laying down the standards for adding to the system?

DK: I expected that my analysis of the essential distinctive tenets of Objectivism would generate discussion, debate, and refinement. But I’m not aware of any such efforts by other people. I may have missed something—I haven’t read all the online debates, nor everything in print. And those who believe Objectivism is closed would not offer any update because they hold that the philosophy includes everything Rand said (in philosophy).

DK: I expected that my analysis of the essential distinctive tenets of Objectivism would generate discussion, debate, and refinement. But I’m not aware of any such efforts by other people. I may have missed something—I haven’t read all the online debates, nor everything in print. And those who believe Objectivism is closed would not offer any update because they hold that the philosophy includes everything Rand said (in philosophy).

VK: But then why did IOS/ TAS not pursue this as their foremost task, of documenting further the distinctiveness of Objectivism and laying down the standards for adding to the system?

DK: Having put forward a case for open Objectivism in The Contested Legacy of Ayn Rand, it was incumbent upon me to distill an essence of Objectivism, and I offered a version. Those who believed in the closed version, of course, rejected the task as invalid.

However, in my own mind, everything I grasp in Objectivist philosophy is part of my Objectivist framework. Back in the day, before the split, I had many discussions about various philosophical issues with many who no longer talk to me. They didn’t agree with each other and/or with me over issues such as ethics and mind-body dichotomy, etc., and yet they were astonished when I said that’s the way it should be.

But I am not that interested in defining the limits of, or the criteria of, who is or who isn’t an Objectivist. I want to do Objectivism. I want to advance the knowledge.

It’s not so important to me what the essence of Objectivism is, as what the next problem I want to solve is. I am a philosopher first, and an Objectivist second, and that’s the only honest way to be in this profession. But we do need a conceptual map of positions that make us distinct from say, socialists, or evangelicals, or post-moderns. One advantage of such a shared map of ideas is that, in such defined company, we can dig deeper into issues rather than arguing about the more fundamental ones.

VK: Back in 1990, you also stated that Objectivism is incomplete as a philosophy. Help us understand where the significant gaps are. Are there also, in your opinion, any holes, inconsistencies, or errors in the system as is?

DK: There are significant gaps in the theory of propositions, induction, and certainty; the ethics of families; and legal philosophy. Some of these issues are being addressed by scholars on both sides of the divide.

As for errors or inconsistencies: If I thought there are problems with the essential principles I described in Truth & Toleration, I would not consider myself an Objectivist. Beyond that, I don’t even start to see issues until I get pretty far down into philosophical details.

VK: Where can one go to learn more about these gaps in induction and certainty theory?

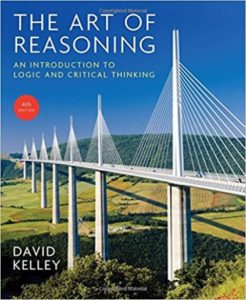

DK: I dealt with the logic part of the generic induction problem in The Art of Reasoning and in my lectures on “Universals and Induction.” To some extent these gaps were addressed in The Logical Leap by Leonard Peikoff and David Harriman. Ironically, Dr. Peikoff seemed to imply that this work was part of Objectivism, even though Rand had mentioned it as an issue she needed to address and hadn’t addressed. That aside, it is fascinating work.

DK: I dealt with the logic part of the generic induction problem in The Art of Reasoning and in my lectures on “Universals and Induction.” To some extent these gaps were addressed in The Logical Leap by Leonard Peikoff and David Harriman. Ironically, Dr. Peikoff seemed to imply that this work was part of Objectivism, even though Rand had mentioned it as an issue she needed to address and hadn’t addressed. That aside, it is fascinating work.

VK: Looking back, what are The Institute for Objectivist Studies (and its successor organizations)’s most important achievements?

DK: Repairing relations with libertarians. Benevolence as a virtue. The spirit of openness in our conferences and other programs. Contributions to the Atlas Shrugged films.

VK: In the direction that you chose, i.e., a new organization to promote a system-building approach to Objectivism, you had the support of some wealthy donors. But in 27 years, the organization’s annual budget never got much over $1 million. Help us understand that.

DK: There are a number of factors: my limits as a persuasive fundraiser; the financial crises (dot-com in 2001, the meltdown in 2008-09); the aging of initial donors.

VK: In 1990, you staked your reputation on the proposition that Objectivism can be regarded as a unique system that can be built upon. What are the new contributions that you are aware of, made by any thinker in any field, which ought to be included in the system if it were to be universally accepted as open?

DK: TAS has developed or showcased a number of refinements, including points Will Thomas and I made in Logical Structure of Objectivism, and my book on benevolence, and David Ross’s work on how to apply the Objectivist theory of concepts to the mathematical concepts of numbers. It’s something Rand hinted at, but never developed. David Ross has taken that a long way.

David Mayer has used the contextual theory of knowledge to provide a constitutional theory of interpretation. ARI-affiliated scholars have also done good work in various areas.

Elsewhere, I mentioned David Harriman and Leonard Peikoff’s own work (The Logical Leap).

VK: That’s very gracious of you, citing Dr. Peikoff’s work.

DK: Thank you.

The Future of Objectivism:

VK: To bring Objectivism to the masses, is a crusade needed on four fronts: Marketers who spread Rand’s works to the masses, (public) Intellectuals who use its foundations to opine/ blog on current issues in the media, Scholars to refine and expand the work and build bridges to academe, and Artists, who convey the Philosophy’s sense of life in creative works?

DK: Yes, to all of these. And I would add student activists who can be active on campuses.

VK: Which of those will you be focusing on? And what is your expectation of The Atlas Society’s focus going forward?

DK: TAS is currently focusing on student outreach through social media and partnerships with organizations like Students for Liberty and Turning Point.

I plan to devote most of my time to philosophical work, mostly in epistemology.

VK: Are you satisfied with the way the Atlas Shrugged movie trilogy came out? Did it succeed in securing more interest in Rand’s work?

VK: Are you satisfied with the way the Atlas Shrugged movie trilogy came out? Did it succeed in securing more interest in Rand’s work?

DK: The films certainly could have been better. They had severe limits in budget and production time. But they certainly did help boost attention to Atlas Shrugged, the book.

VK: Are there any plans to acquire screen rights to The Fountainhead?

DK: Warner Bros. held the rights to The Fountainhead and I believe those rights were acquired by the Turner Network. I have heard a rumor that Brad Pitt would like to be involved. I liked the forties movie version, but Gary Cooper didn’t quite cut it. I would love to see a modern version on screen again, but only if it’s done really, really well.

About You:

VK: Which is your favorite Rand novel/ story and why?

DK: My favorites are The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged. Between them, my favorite is whichever I read last. Seriously, each has distinctive literary merits and evocative power.

VK: How do you unwind? Any sports you play or follow? Favorite music? Cuisine? Tell us more about David Kelley, the person.

DK: I unwind with books, fiction and nonfiction, especially about history; conversations with people I meet; working with my hands (building things, gardening).

VK: Can an intellectual ever retire? Can a mind used to thinking on a complex and abstract level ever give that up?

DK: I can’t, as long as I feel I’m up to the subjects and challenges that interest me.

Reflections on a 50-year Journey:

VK: Have you made a special study of Cognitive Science and the workings of the mind? How would one use advances in knowledge there, or in the sciences generally, to expand Objectivism?

DK: I studied many areas of cognitive science, especially when I was teaching at Vassar and part of a Cognitive Science program, and for the epistemological writing I did in the ‘80s. Not so much since then. But I’m currently reviewing work on cognitive biases in connection with a new edition of my logic textbook, The Art of Reasoning.

VK: What do you believe to be your best philosophical work and why?

DK: I would say that my best work has been in epistemology, including the 1980s articles and Evidence of the Senses, and, on a different level, Unrugged Individualism, my short book on benevolence.

DK: I would say that my best work has been in epistemology, including the 1980s articles and Evidence of the Senses, and, on a different level, Unrugged Individualism, my short book on benevolence.

VK: If you had to live your life all over again, would you make the same key career choices you have? Specifically, do you think it would have been easier, as against creating a rival Objectivism school (or indeed, is it still viable), to build on Rand’s system by including her as a neo-Aristotelian in a Eudemonism School, or by giving Rand pride of place in the pantheon of Enlightenment thinkers, or does Rand’s distinctiveness set her too far apart?

DK: George Walsh and I discussed this very question extensively in founding the organization. We concluded—and I still believe—that we have to fight for the soul of Objectivism as a distinctive philosophy.

I will let my case for open Objectivism stand on its merits. I have not lost the conviction that this approach would attract the most creative, independent, and smartest people even as I recognize that there are some really smart people on the other side.

We are in a growth phase of a young philosophy. I don’t expect to see a huge change in my lifetime. I wanted to lay a basis for what I considered to be the proper approach.

I will let my case for open Objectivism stand on its merits. I have not lost the conviction that this approach would attract the most creative, independent, and smartest people even as I recognize that there are some really smart people on the other side.

VK: Is the soul of Objectivism contained in its name though?

DK: If we were to call ourselves “The New Enlightenment” or “The New Aristotelians,” we would have to fight in a sense even harder to bring out what’s distinctive about Rand, e.g. even though Aristotle was a eudemonist, did he ever say that self-sacrifice is evil, that it is destroying the world? That it’s a travesty of ethics? Only Rand had the “balls” to say that. That’s why it’s important to fight for the name and the ideas that are more specific than Aristotelianism.

VK: What about the invitation to Nathaniel Branden to rejoin the movement? Was that crucial?

DK: Yes, the invitation to Nathaniel was crucial. We invited him to speak about psychology and philosophy, not his relationship with Rand. It was the clear-cut proof that we were distinguishing the ideas of Objectivism from personal relationships.

VK: Did any fans and trustees who otherwise supported open Objectivism leave because of this invitation?

DK: Yes, there was fallout from that among trustees, board of advisors, and donors. There were people who took exception to the decision. It didn’t change my mind that this was the right thing to do, but it was painful.

The relevance of Branden’s work in psychology is primarily to ethics, and, to some extent, to the theory of rationality, especially to the practice of rationality.

VK: Do you regard Branden’s work in psychology as a crucial addition to the Objectivist corpus?

DK: The relevance of Branden’s work in psychology is primarily to ethics, and, to some extent, to the theory of rationality, especially to the practice of rationality. There is a difference between philosophical ethics and psychology, but also a connection. The theory of visibility underlies the entire ethic of romantic love and friendship in Objectivism. Self-esteem is one of the cardinal values in Objectivism, and Branden’s work adds to what Rand wrote on the subject.

Much of what Branden has written can be interpreted as addition, expansion, and application of Objectivist ethics, enriched by psychological insights that he had.

VK: Many thanks for giving us so much of your time, David.

VK: Many thanks for giving us so much of your time, David.

We are watching this battle for the “Soul of Objectivism” as you termed it, with interest, but more than anything else, we wish for you more happiness, and, commensurate with that, even more intellectual achievement and flourishing in your “retirement.”

DK: Thank you.

This interview benefited from questions suggested by Walter Donway, Brishon Martin, Donna Paris, and Marsha Enright, and from editing by Brishon and Donna. The lead photo was taken by Judd Weiss at the Atlas Summit in June 2012.

The Savvy Street thanks them all.