American Pastoral

A book review of Philip Roth’s Pulitzer-Prize winning American Pastoral.

It’s the early 1960s and your life is so good that it is not the stuff of literature.

So you’re a blond-god star athlete, running a factory you inherited from your father (and doing a good job of it). You’re liked and desired by everyone, but faithful to your beauty-pageant-winning wife. You’ve got a great house in the countryside of New Jersey and a little girl who adores you. It’s the early 1960s and your life is so good that it is not the stuff of literature except maybe for pastoral, the genre of poetry that celebrates happy rural life. This is how Philip Roth’s 1998 Pulitzer-Prize winning novel begins.

Unexpectedly, something goes hideously wrong with your perfect universe. Is it cancer? No, everybody dies of something and you are not afraid of death. It’s far worse than cancer. Your daughter, intelligent but stuttering, hits puberty and becomes the adolescent from hell. She is angry about the Vietnam War and about complacent capitalists at home. She back-talks you incessantly. She wants to stay overnight in New York City when she’s 15, crashing with a radical couple she’s just met up with.

But wait, it gets worse. She decides it’s time to “bring the war home,” as New Leftists said about their demonstrations. So at the age of 16, she plants a bomb in the local post office and blows it up. It’s the middle of the night, but what she didn’t plan on was the kindly local doctor being there to mail a letter. He is killed instantly. And now your daughter is a murderer and a fugitive.

This is the story of Seymour Levov, a second-generation American Jew with looks so Nordic that everyone calls him the Swede. His daughter is Merry. Well, actually, she’s anything but merry; it’s short for Meredith. The Swede spends the rest of his days after the cataclysm trying to figure out what went wrong, to deal with the consequences, to find his daughter and maybe, somehow to get on with his life.

This is the story of Seymour Levov, a second-generation American Jew with looks so Nordic that everyone calls him the Swede. His daughter is Merry. Well, actually, she’s anything but merry; it’s short for Meredith. The Swede spends the rest of his days after the cataclysm trying to figure out what went wrong, to deal with the consequences, to find his daughter and maybe, somehow to get on with his life.

Although the book is a little slow getting through Seymour’s youth, once it gets to Merry’s adolescence and misdeed (later, misdeeds), it does not just sizzle, it sears. It takes the agony of this decent but limited man and makes it into art that resonates.

Despite appearances, this is not a tale set in a malevolent universe. It is not saying that happiness is an illusion. Rather, it acknowledges a simple fact of the world that if you have children they are independent beings who will have the power to rip you apart. If you can’t deal with this fact, don’t have children. The ironically-titled American Pastoral takes this point and sharpens it like a scalpel.

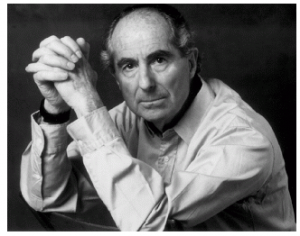

But author Philip Roth does not apply his scalpel just to this lucky-then-unlucky family. He dissects the America of the sixties and specifically his beloved hometown of Newark, New Jersey, which became a hellhole in that period. He wants to know: What went wrong with the American Dream?

But author Philip Roth does not apply his scalpel just to this lucky-then-unlucky family. He dissects the America of the sixties and specifically his beloved hometown of Newark, New Jersey, which became a hellhole in that period. He wants to know: What went wrong with the American Dream?

The story is told by Nathan Zuckerman, who is a fictional New Jersey author created by Roth and used in several of his novels as his stand-in. As in The Human Stain, Zuckerman finds out a few details of an interesting man’s life-story and speculatively spins a narrative out of it. It might bother the reader that Zuckerman speculates so much until you realize that all novels are just made-up stories anyway. Apparently this is something called “metafiction,” and it makes the reader think about just how much we know about those around us and what mysteries lie behind seemingly content eyes.

Zuckerman knew the Swede slightly as a child. He was in the same class as the Swede’s younger brother Jerry, who regularly annihilated Zuckerman at ping-pong in the Levov’s basement. Jerry has all the anger in the family.

By contrast, the Swede was a good boy, a decent boy. He never lets his many successes on the playing field go to his head. Despite being incredibly adored by everyone around him, he has no sense of entitlement and is always reasonable. The thought of using physical force is repugnant to him, even on those rare occasions when it might have been a good idea. (Although when a neighbor gets too grabby in an adult game of touch football, Seymour knocks him on his butt to teach him a lesson.)

Seymour and Jerry form a dyad. Seymour goes along with his domineering father’s plans for him and enters the glove-making business, while Jerry tells his father to fuck off and becomes a heart surgeon, a profession in which he can shout and always be right (just like his father). He marries four times to the shame of his parents, and has many kids by several mothers.

This contrast between the brothers is telling. When Merry runs away, Jerry thinks she is a little bitch and that Seymour is well rid of her, while Seymour can’t give up on her and can’t help agonizing over what caused Merry to do what she did. Was it anger over the stutter? Was it the one time he kissed Merry on the mouth like an adult when she was 12 (and she asked him to)?

This summary does not do justice to the complexity of the novel. For example, one fascinating subplot involves a tiny New Leftist woman who calls herself Rita Cohen. She looks like a doll with black revolutionary icon Angela Davis’ big afro. She comes to Seymour pretending to want to learn about the factory, and Seymour takes her through the whole glove-making process, creating a pair for her from start to finish. Then “Rita” reveals that she is an emissary from Merry, who wants some of her things.

When Seymour tells him that he’d like to see his daughter, Rita tells him that Merry would rather see him shot as an exploitative capitalist. Seymour has several encounters with Rita, each more taunting and cruel than the one before, until Rita starts acting like the demon-child from The Exorcist. There is a good chance that Zuckerman has created Rita in his factory, but if you know anything about sixties radicals, you know that she’s quite plausible.

Another gripping subplot concerns the destruction of Newark, first by slow decline in the fifties and then by race riots in the sixties. Only the efforts of Seymour’s black forelady, Vickie, spares the Swede’s factory from major destruction.

Another gripping subplot concerns the destruction of Newark, first by slow decline in the fifties and then by race riots in the sixties. Only the efforts of Seymour’s black forelady, Vickie, spares the Swede’s factory from major destruction.

Philip Roth and his creation seem to be fairly standard liberals, definitely New Deal Democrats, although appreciative of capitalism at its best. They are against the Vietnam War, which opposition they expressed peacefully. But Roth’s analysis of sixties radicalism and the nature of the Swede’s capitalist enterprise would gladden the heart of even an Ayn Rand.

The Levov family earns their wealth through hard-work, exacting standards and (at least in Seymour’s case) respect for the workers. It is an immigrant success story. Seymour gives people opportunities and they are loyal to him, at least until the workforce declines after the riots. He is not “exploitative”: He opens a second factory in Puerto Rico and it is a not a sweatshop, but a place where people learn a skilled trade.

Merry, especially through her mouthpiece Rita, regards Seymour as little more than a colonialist bandit. They know nothing about real capitalism. Theirs is the politics of resentment.

Merry combines adolescent rebellion with contempt for her father’s authority on political-moral grounds and so is easy prey for revolutionary ideologues.

And beneath this resentment is the morality of altruism (in the sense of always putting others above self, not in the common use of the term to mean generosity). Merry cannot stand to see America prosperous and at peace, while the Vietnamese are being destroyed by war, even though the war was instigated by the Communists. Merry combines adolescent rebellion with contempt for her father’s authority on political-moral grounds and so is easy prey for revolutionary ideologues.

Merry’s altruism is confirmed by what she does to herself later, which is almost too horrible to contemplate, but which the reader must bravely face.

And now we are getting near the heart of Roth’s analysis. The Swede is a non-observant Jew. His wife is a non-observant Catholic. They believe in what you might call “Americanism.” But this Americanism has no philosophical roots. It’s just based on good character and gratitude for the opportunities America provides.

Merry, on the other hand, is politically speaking a vacuum. She never has to work for anything. She is an empty vessel waiting to be filled by whatever intellectual cant that is in the air when she comes of age. There are hints that this is worsened by the anger her stutter arouses in her and by her mother’s attempts to make a little fashion plate out of her. But the main problem is that the American pastoral narrative is without a solid foundation. The final sequence, a long account of a dinner party with a goading leftist professor as one of the guests, makes it clear what really happened to Merry: the intellectual culture captured her.

The Swede never figures this out, although he comes close. It’s not clear that Zuckerman, or for that matter, even Roth, have it all explicitly figured out either. No one makes speeches in Philip Roth’s novels, although they tell great stories and make pointed observations about character.

You get an account of what happened in America in the sixties and early seventies from the point of view of a representative American.

This is a painful novel to read. You really sympathize with Seymour’s anguish over his daughter. But reading it has (at least) two benefits: First, you get an account of what happened in America in the sixties and early seventies from the point of view of a representative American. It’s a great before-and-after picture. And second, you see all that suffering given meaning as it is elevated into art.

I found the novel a transformative experience. I would never want to live on a steady diet of bewildered, albeit decent, characters in pain. Heroes are needed to feed the soul. But I also need to look at my country and understand what has happened to it, and I need to know why things can go wrong, even in a seemingly charmed life (which symbolically are the same thing). These are not easy matters and Roth does not give us easy answers. But somewhere in his perceptiveness and honesty lies a kind of answer, if you are courageous enough to surrender to the experience of this powerful story.

« Intolerable Dreaming Can Money Rig Elections? Can it Buy Politicians? »