Ayn Rand and the Cognitive Science of Narrative

Cognitive Science, the scientific study of the mind and its processes, has been researching the question of why humans are pervasive consumers of story, and how it affects us.

In The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make us Human, author Jonathan Gottschall makes a compelling case that stories help us learn and navigate through life’s problems, in the way flight simulators assist pilots in training. Asserting that humans are genetically programmed for narratives and archetypes, Gottschall quotes neuroscience researcher Michael Gazzaninga—“It [the brain] is addicted to meaning. If the storytelling mind cannot find meaningful patterns in the world, it will try to impose them. In short, the storytelling mind is a factory that churns out true stories when it can, but will manufacture lies when it can’t.”

This is why archetype stories stick in one’s mind and the lessons, even if untrue, survive the truth being outed—the mind does not like to let go of a framework it holds as a way of managing life.

Engagement with the narrative, as well as identification with characters, serves to increase persuasive impact through reducing the formation of counterarguments, lessening message scrutiny, and inhibiting psychological resistance.

Cognitive Science researcher Melanie Green (State University of New York), who examines the power of fictional stories on real world beliefs, infers that individuals tend to generalize from stories, even though narratives are about a few key people, a statistically insignificant sample.

With such fondness for story inherent in humans, is critical thinking lowered when our fancy is grabbed by an interesting yarn?

Yes, says Associate Professor Michael Dahlstrom of Iowa State University. Models of persuasive narrative infer that “engagement with the narrative, as well as identification with characters, serves to increase persuasive impact through reducing the formation of counterarguments, lessening message scrutiny, and inhibiting psychological resistance.” So strong is the power of narratives in fact, says Dahlstrom, that “the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have begun working with Hollywood to monitor the truthfulness of medical information in television dramas.”

However, is this persuasion temporary? In other words, is our critical faculty, sedated as it is by the emotional high of narrative, cleaning up after the emotional roller-coaster ride is over?

No, says Dahlstrom—“Results from belief-based studies, which examine the acceptance of specific, factual assertions made within narratives and their incorporation into mental belief structures about the world, generally find that individuals do tend to accept narrative assertions and utilize them to answer questions about the world.”

Beliefs acquired by reading fictional narratives are integrated into real-world knowledge.

Cognitive Psychology researchers Markus Appel (University of Koblenz-Landau, Germany) and Tobias Richter (Universität Kassel, Hessen, Germany) made an even stronger inference—“persuasive effects of fictional narratives are persistent and even increase over time” (they label it the absolute sleeper effect) and that “beliefs acquired by reading fictional narratives are integrated into real-world knowledge.” Future intake of information is processed by an existing framework that we hold dear, because humans need frameworks to deal with a complex world; logicians may call this confirmation bias.

So stories that connect with us emotionally leave an indelible imprint on our psyche.

In 2011, the New York Times even posed this question as a headline, “Can a novelist write philosophically?” drawing on the work of a teacher of philosophy at Oxford, Iris Murdoch, who wrote novels, and Philosophy PhDs who wrote novels such as Rebecca Goldstein and Clancy Martin, as well as David Foster Wallace (a one-time philosophy PhD candidate at Harvard).

Among famous philosophers, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote plays, and George Santayana wrote poems.

But the New York Times misses the point entirely. All narratives express a philosophical worldview since the author must select the subject, the context, the events, and draw the characters and express their choices. Whether implicitly or overtly, a novelist cannot but express a philosophical position, so the question is redundant.

Enter Ayn Rand, probably the most famous formal philosopher who chose to express her worldview quite overtly within a narrative form. Rand had perceived the issue which the New York Times quotes as, “Philosophy is written for the few; literature for the many.”

Given that stories are “the flight simulators of life,” particularly for the young, who are often voracious consumers of stories, what is a good basis for judging how good these simulators are?

Rand in fact exited the stage (she passed in 1982) well before 21st century cognitive science confirmed her reasoning about the power of narratives to teach and affect, and even to change a worldview inexorably, particularly in the young. In The Romantic Manifesto: A Philosophy of Literature, published in 1971, Rand articulated the simulation learning effect—“Without the assistance of art, ethics remains in the position of theoretical engineering; art is the model builder. Many readers of The Fountainhead have told me that the character of Howard Roark helped them to make a decision when they faced a moral dilemma.”

Given that stories are “the flight simulators of life,” particularly for the young, who are often voracious consumers of stories, what is a good basis for judging how good these simulators are?

Rand’s work provides one such framework. Using literature as the primary exposition tool, Rand constructed a dichotomy which addresses the making of art in a most fundamental way—she designated that as Romanticism vs Naturalism. It does not mean that every artistic work is completely one or the other; most in fact are mixed; there is a spectrum, not two boxes, nevertheless it assists us to identify the two bookends of the spectrum.

Rand redefined Romanticism, then a pre-existing literary movement, as “a category of art based on the recognition of the principle that man possesses the faculty of volition, and Naturalism, as the category that denies it.” Romanticism “showcases” purposeful action by which men and women try to shape the world around them as against being shaped by it.

The medium of film is tailor made for showcasing purposeful action, so let’s look at a few illustrations from the world of screen stories that elucidate this dichotomy. The examples are drawn from “Do Film Critics Understand Film?” which is a fuller treatment of how film critics have convoluted standards. Film critics may subconsciously serve a leftist purpose as defeatist narratives sweep the world of art.

“Show, don’t tell”—the filmmaker’s Holy Grail—is also about connecting at an emotional level with illustrative concretizations—not speeches, essays, and tirades. Every story has a moral. When the narrative ends, there is always an underlying message, best kept implicit. If nothing of consequence happens, the subliminal inference that your subconscious takes in, is that human life is about chance, ordinariness, or even despair if it all ends badly without hope. If consequences are dictated by coincidences, the young would infer that life is about destiny. But story events propelled by humans in purposeful conflict suggest the opposite.

Consider for example, the film The Counterfeiters (2007).

Based on a true WWII story, this German-language film is a telling of an incredible internal value-clash within a Jewish artist, Salomon Sorowitsch (Sal). Sal makes a living as a forger of passports and currency. The Nazis hunt him down and send him to a concentration camp. Here, he uses his portraiture skills to get himself a better bunkhouse and food.

The Nazis want to use him to forge the British Pound and the U.S. dollar. Initially motivated by survival, he is conflicted by the fact of the counterfeiting assisting the Germans in the war, and further conflicted by the pride he takes in his work—he has never been able to perfect his counterfeit of the U.S. dollar, and the Germans are throwing money at it. His fellow prisoners are on both sides of the debate—is it better to die honorably now, or die after helping the Nazis while retaining a slim possibility of escape? Sal engages in covert delaying tactics to buy time, which starts an engrossing cat-and-mouse detection game among purpose-driven humans in conflict who shape events via their struggle. It won the best foreign language film Oscar for 2007.

Now, consider these instead:

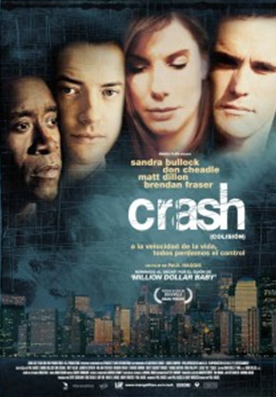

Crash (2004): Using an enormous ensemble cast, with no singularly visible protagonist, and no definitively pursued desires against an ascending conflict, the story liberally uses repetitive coincidence as a plot device to demonstrate that victims of racism are often racist themselves in different contexts and situations in a world full of moral gray. Critically acclaimed, Crash won two Academy awards, including Best Picture, and two BAFTAs (including Best Screenplay).

The Hurt Locker (2009): One of the most plot-less stories ever to hit the screen, this is a journalistic slice-of-life account of unconnected incidents that befall a bomb-explosives expert. At the end, he confesses to his infant son that the risky excitement of war is his only true love. This film won six Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Screenplay, and Best Director, and substantive critical acclaim.

These Best Screenplay winners are narratives that feed a sense of helplessness, resignation, and determinism. They are inculcating the wrong lessons.

Having conflicts unresolved at the end, implies subliminally that resolution is not likely in real life. Having accidental or coincidental events determine the fate of the key characters conveys the meaning that accidental events are the key to outcomes. Portraying a plotless character study, without setting a context for a universal truth about humankind, violates even the educational purpose of art, let alone the inspirational. The repetitive depiction of a world full of moral gray engraves a pessimistic streak in the viewer’s mind.

This is obnoxiously lazy writing, lazy in the sense that the writer is unwilling or unable to undertake the large amount of thinking that is necessary to write a fully integrated plot and express it well. To elevate such writing to world-class with pseudo awards only deepens the confusion in the young mind.

People with an achievement oriented outlook on life, love the triumph of an integrated plot. Only the narrative with a non-defeatist perspective grips them; it tells them that, for good or bad, humans shape their destiny. It is much harder to create such a narrative as compared to a meandering navel gazing story, but it is the higher form of art. It is the genre which is consonant with the spirit of enterprise, daring, and self-reliance.

Film critics however, have long since completed their journey into the dark world. For sixty consecutive years (1952-2012), film critics classified a wayward examination of an unhappy newspaper baron (Citizen Kane) to be the greatest film of all time, offering little more than new techniques at the time and a gimmicky narrative structure as the reasons thereof. Citizen Kane is a purposeless story, essentially an inferior screenplay. Perhaps, like their literary counterparts, they did not dare to state the real reason—Orson Welles made Naturalism chic and initiated the debasement of humanity in movies in 1941. Citizen Kane was initially a commercial failure, until it received a glowing recommendation—the kiss of existentialist despair, from Jean-Paul Sartre. Then the critics began to fawn over it.

Since then, film critics have often elevated the mundane to a mountaintop alight with pompous glory. Their pretentious literary and visual art cousins had paved the way. For how far in the gutter modern art has landed, see Emptiness and Nausea in Modern Art by Stephen Hicks.

The flight simulators that are teaching our young pilots how not to fly, are being heralded as sublime works of art.

A writer’s subconscious will always show through his or her work by the act of selection. The work speaks to us at a subliminal level. We respond positively when it accords with our own worldview. And in the young, it can shape their worldview.

That is why we need to pay attention here—the flight simulators that are teaching our young pilots how not to fly, are being heralded as sublime works of art.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

References:

1) Appel, Markus, Fictional Narratives Cultivate Just‐World Beliefs, Journal of Communication, 2008, Vol.58(1), pp.62-83

2) Appel, Markus & Richter, Tobias, Persuasive Effects of Fictional Narratives Increase Over Time, Media Psychology; 2007, Vol. 10 Issue 1, pp 113-134

3) Dahlstrom, Michael F, The Persuasive Influence of Narrative Causality: Psychological Mechanism, Strength in Overcoming Resistance, and Persistence Over Time, Media Psychology, 2012, 15:3, pp 303-326

4) Gottschall Jonathan, The Storytelling Animal: How stories make us human, Houghton Harcourt, 2009

5) Green, Melanie C, Research challenges in narrative persuasion, Information Design Journal, Volume 16, Number 1, 2008, pp. 47-52(6)

« How Can Greece Survive? Conservatives against the Core Principles of Capitalism »