Translating deep thinking into common sense

Does the Fed Print Money? Or Just Create Credit?

By Keith Weiner

January 17, 2016

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

There is a populist idea of money printing. The idea is that banks can just print what they want, enriching themselves in a massive fraud. But, does it really work this way?

Let’s start with a simple case, which is clearly not money printing. We will build a series of examples by adding one element at a time, working our way up to banks, and eventually the central bank. Then we can examine this idea of printing.

Creditors today accept central bank liabilities only because they are forced to. Central banks have no incentive for prudence.

Henry Homeowner finds the perfect house, goes to a bank and gets a mortgage. He is clearly not printing (the bank isn’t printing what it lends to him either, so please bear with me until the end). This example illustrates the concept of the balance sheet. Henry did not get one penny richer merely by borrowing to buy the house. It is true that he now has a house, an asset he did not own previously. However, the house is balanced by a mortgage, a liability he didn’t have before, either.

Next is Barry Bondholder, who gets a loan to buy a bond. Now he has an asset (the bond) and a liability (the loan). Would anyone say that Barry printed money? Barry is only different from Henry, in that he bought a bond instead of a house.

Next, consider the case of Frank Flipper. He takes out a balloon mortgage to buy a house. He paints over the olive drab walls, and adds some new carpet without cat pee. He sells the house for a profit, and repays the mortgage. Then he does it again. Is Frank printing money while he flips houses? Frank differs from Henry, in that he has to sell the asset to repay his short-term funding.

Frank’s brother, Magnus, scales up Frank’s business. He sets up a process with the bank to automate borrowing and repaying. Funding the mortgage to buy a house is as simple as pressing a button. When he sells, another button repays the mortgage. He develops such high turnover, that he is always buying a new one just as he is selling an old one. The loan repayment of one replenishes his credit, just in time to get the next one. Is Magnus printing money? Magnus is different from Frank, because his good credit persuades the bank to give him discretion to initiate his own loans.

Next let’s look at Bob Banker, Barry Bondholder’s cousin. Bob sets up a credit line to grow his bond business. When he finds a good bond, he can hit a button to borrow the funds to buy it. Would you say that he’s printing money? Like Magnus, Bob can borrow what he wants.

Bob’s son, Morgan, expands the family bond business by borrowing from retail savers and corporations. Does Morgan finally cross the threshold into money printing? Morgan is different from the others. Morgan’s business is a bank, using depositor money.

Finally, let’s look at Bill Trader. His firm buys and sells Morgan Banker’s debt. He is a market maker, and his trading provides liquidity to Banker debt paper. He is so successful, that wholesalers begin to accept it in payment of their invoices, because it suits them better than the alternatives. Does Bill turn Morgan into a money printer?

These examples could all take place in a free market, but unfortunately, we don’t have one. We have central banks. A central bank is similar to Henry, in that it issues liabilities to fund the purchase of assets. Like Barry, the central bank does not deal in houses, but bonds. Like Magnus and Bob, the central bank has discretion to issue liabilities whenever it wants to buy an asset.

A central bank is quite different, but not because it can print money. Unlike the wholesalers who accepted Banker paper, creditors today accept central bank liabilities only because they are forced to. Central banks have no incentive for prudence, as Bill and Morgan did. The law gives them cover to dispense with any need for care, or even honest dealing. Demand for central bank debt paper is seemingly unlimited, at least so far.

“Money is gold, and nothing else,” said John Pierpont Morgan, in his testimony before Congress in 1912.

The central bank is not printing, but borrowing. It does not get anything for free, but merely expands its balance sheet. It has a new liability to balance its new asset. In our banking system, there is no such thing as printing. Also, despite popular misconception, the debt paper of the central bank is not money, but credit. We’ll let an expert banker give the proper definition.

“Money is gold, and nothing else,” said John Pierpont Morgan, in his testimony before Congress in 1912.

But just because the central bank is not printing, it does not mean that it’s not doing something copiously dangerous. Like other central banks, the U.S. central bank, the Federal Reserve, was ostensibly created to inject more stability in the economy.

Mainstream economists tell us that the Federal Reserve protects us from economic waves, indeed from the business cycle itself. In their view, people naturally tend to go overboard and cause wild swings in both directions. Thus, we need an economic central planner to alternatively stimulate us and then take away the punch bowl.

Prior to the global financial crisis of 2008, a popular term described the supposed benefits created by the Fed. The Great Moderation referred to the reduced volatility of the business cycle. For example, I have written before about economist Marvin Goodfriend, who asserted that the Fed does better than the gold standard.

This belief is inherent in the Fed’s very mandate from Congress. The Fed states its three statutory objectives as, “maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” These terms are Orwellian. Maximum employment means five percent of able-bodied adults can’t find work. Stable prices are actually rising relentlessly, at two percent per year. The meaning of moderate long-term interest rates must be changing, because rates have been falling precipitously for a third of a century.

The business cycle is vastly more complicated than the crop cycle. It plays out over decades. It involves every participant in the economy. It affects every price, including, and especially, the price of money.

That aside, the basic idea is that the Fed has both the power and the knowledge to somehow deliver an economic miracle. However, we know that central planning never works, even for simple things such as wheat production. Communist states have invariably failed to produce the food to keep their people alive. Stalin, Mao, and other communist dictators have deliberately starved off segments of their populations that they couldn’t feed.

The business cycle is vastly more complicated than the crop cycle. It plays out over decades. It involves every participant in the economy. It affects every price, including, and especially, the price of money. It causes changes in how people coordinate in the present and how they plan for the future. And, there are feedback loops. Changes in one variable cause changes in others, which come back to affect the first variable. The very idea of centrally planning money and credit boggles the mind.

This should not be controversial. Yet, even those who know why government food planners fail, somehow retain their faith in central planning of the economy as a whole. Marvin Goodfriend—who spoke in favor of free markets, by the way—called his faith in central banking, “optimism.”

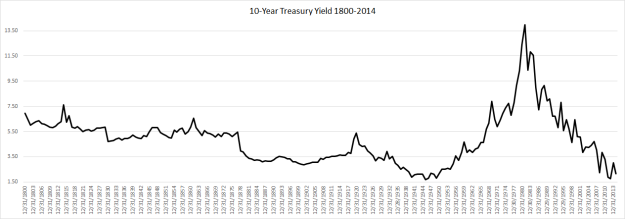

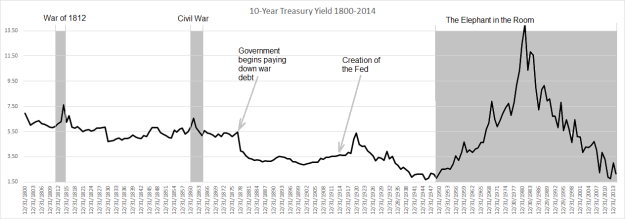

Is it true that the Fed is actually somehow providing stability, or even improving on a free market? Let’s look to the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury bond. The rate of interest is a key economic indicator.

With that giant peak on the right side of the graph, we can immediately reject all claims to Fed-imposed stability.

Now let’s label a few key dates.

(Sources: National Bureau of Economic Research 1800-2001, US Treasury 2002-2014)

The pre-Fed period is pretty stable. Two spikes occur due to wars that we know disrupted the economy—and they’re pretty small, considering the post-Fed period volatility. Interest declines to a lower level when the government was paying down its war debt. Things remain stable until the creation of the Fed.

After that, we get a rise, a protracted fall, an incredible and truly massive rise, and an endless freefall. Both rising and falling interest make it more difficult to run a business that depends on credit, such as manufacturing, banking, or insurance. The post-Fed period is a lot less stable than the pre-Fed one.

A feature of the free market and its gold standard is interest rate stability. The rate can vary between the marginal time preference and marginal productivity. This tends to be a stable and narrow range.

Fed apologists argue that the economy would be even more unstable, if we had no monetary central planner. However, the fact is that it became a lot less stable after the Fed was created.

And that’s what we should expect if we insert into the economy, an entity that can borrow with reckless abandon, unconstrained by economic law. Never mind the fact that it can’t print money.

The bulk of this essay appeared across two articles from Keith Weiner’s weekly column, called The Gold Standard, at the Swiss National Bank and Swiss Franc Blog SNBCHF.com.

But why does money always have to be gold? Aren’t there other commodities that could be better? More useful commodities? Or, a basket of commodities? And, if it must be gold, then why must it be mined and refined? Can’t the government just leave the gold in a mountain and say it’s the gold reserve without ripping down the mountain and running all the dirt through an environmentally destructive refining process? Digging up the gold, then refining it, then putting it back underground at Fort Knox seems like a lot of pointless and destructive work.

Almost certainly, you are joking, John, and by replying I am letting you lead me by the nose, as they say. But…on off chance, heaven protect you, you are NOT kidding, I have a few comments. If money is to be real–and not created at the whim of anyone–then that money must be very widely acceptable. It is civilization itself, over thousands of years, that has chosen gold. The commodity used as a medium of exchange must have many characteristics, but a very high value per unit is crucial–and it is luxuries that have that value: gold, platinum, diamonds… If people are to accept that money is real and RELIABLE–a good like others except that it is used as a medium of exchange and store of value–then they must know they can hold, store, hide that good. If paper money or checks aren’t fully exchangeable for the gold they represent, they we are back to a fiat currency. We are back to relying on promises. How much has the mining and refinement of gold, and its storage in Fort Knox, cost us as compared with the erosion of the value of paper money over the centuries? Since creation of the Federal Reserve and its control of money and credit, the value of the U.S. dollar has fallen to less than 5 percent of its worth since December 1917. The destruction of the value of the currency accelerated into a rocket since 1971, when Richard Nixon slashed the last connection of the dollar with gold. Everyone who has held dollars since then, here and abroad, has held a rapidly wasting asset. How much was that loss compared with the relatively trivial cost of mining gold? The downside? Well, our leaders–and I used the term very loosely–could not have run up by 2012 some 16.3 trillion in debt. Under the gold standard that would be utterly impossible, unthinkable. And so…not much of a welfare state, not many dubious wars, and not a Congress that buys for itself a 95 percent-plus re-election rate… The fully convertible gold standard to under gird the value of our money is nothing less than a last line of defense against our internal barbarian hordes, against the sacking of the wealth, and enslavement of the productive, in our civilization.

A completely meaningless statement, because we don’t live in 1917. We have gotten vastly wealthier in real terms since then because it takes substantially less labor now to earn the current money to buy the kinds of goods and services produced a century ago that we still find on the market today, like a pound of bacon, for example. Look up economist Brad DeLong’s essay, “Slouching Towards Utopia,” where he shows his calculations about real changes in purchasing power measured by time. On top of that, we can buy goods and services in 2016 with our Federal Reserve Money which didn’t exist as ideas in 1917. You can buy a month’s worth of generic prescription drugs which work for pocket change, for example.

Perhaps it would easier for you to understand if you stop and think, what is the value of a printed piece of paper which represents money?

Doesn’t have to be gold. However, after centuries of experimentation with various goods as money, gold ends up having superior qualities. Thus consensus has settled on gold. It is scarce, durable, divisible, fungible, portable, verifiable. These are the properties that make for a good money. Gold possesses these qualities more so than anything else. Better than silver even because the best element is useful for absolutely nothing else except being money.

Mr. Weiner has a genius for explaining complex issues. In economics–or, as we say, “macro-economics–that is the great, decades-long scam in the role claimed for the U.S. Federal Reserve, how it carries that scam, and what really results. How can you finish this article and not conclude that what really results is the all-time boom and bust of exactly the aspect of economic life the Fed was created to “stabilize”: interest rates? Mr. Weiner takes us through the economic system in lucid, easy steps, ensuring actual understanding at each stage, and then, when we are ready to grasp what we see, rips the disguise off the Fed and reveals it for what it is: a virtually totalitarian entity in a constitutional democratic government, imposing central planning on the single most vital element of free enterprise: money and interest rates. I find this article reminding me of the great expositor of economics of all time, Henry Hazlitt. I have no higher praise than that.

The gold standard and the cornucopianism of natural resources make contradictory assumptions, so you really have to choose. You see this confusion in Atlas Shrugged, where the men of the mind in a free society could produce all the commodities anyone could possibly need or want based on resources extracted from the earth, including petroleum, shale, coal, copper and steel – but not gold, for some mysterious reason.

Gold has more value than what was produced with petroleum, coal, copper and iron. What is your estimate as to how much in dollar value would a train car cost if it were made of gold?

“why does money always have to be gold?”

Greenspan wrote an excellent explanation.

tinyurl (dot) com/Gold-by-Greenspan

1967 Capitalism, the Unknown Ideal – Gold and Economic Freedom by Alan Greenspan

Thanks for commenting on this article and providing the link. I wouldn’t have come across it myself and I hope the two comments I added make sense. If not, let me know. I don’t want to appear dumber than I am. 😉

Note to SavyStreet:

Your installation of Disqus seems faulty.

I can only read one of the 6 comments (scrolling doesn’t work) and I have a tiny window in which to compose my comment. Such conditions (along with the blocking of live links) are neither friendly nor conducive to reading or posting comments.

That may also explain why you have such a low volume of comments on your other articles.

Will have to check on that. I can see all the 12 comments here, as well as the 20- on some other articles (Rand and Cognitive Science for instance). The window (join the discussion … ) view is thin but it does not limit the size of the comment.