Translating deep thinking into common sense

Self-Perfection as a Paradigm for Ethics: Part II*

By Douglas Den Uyl and Douglas Rasmussen

June 19, 2020

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

This is Part II of the essay. Part I can be found here.

Responsibility Versus Respect

It is quite conceivable that certain 18th century ethicists such as Hume or Smith might fit here, since their focus is arguably to evaluate relations among persons in light of their contribution to well-being.

It should be clear that each of the two basic frameworks discussed in Part I includes a family of implications as a consequence of its adoption. Each template may thus include a large range of ethical theories. For the template of responsibility, we would allow much of ancient ethics, as well as medieval forms that continue that tradition. These might include the standard doctrines of Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics, Aquinas, and the like. It is quite conceivable that certain 18th century ethicists such as Hume or Smith might fit here, as well, since their focus often tends to revolve around the well-being of the agent. Or, to put it another way, their focus is arguably to evaluate relations among persons in light of their contribution to well-being. We have indicated as well that most modern doctrines, whether Kantian deontology or utilitarianism or egoism or altruism or certain forms of sentimentalism, all fall under an ethics of respect. We have noted above that, given what the nature of a “framework” is—namely, that frameworks are inherently archetypical—particular theories may possess some characteristics of an opposing archetype, while yet remaining within a given framework overall. At this level of abstraction, then, the question is whether there are some characteristics common to both archetypes. In our view, there is at least one thing both frameworks have in common, and that is a recognition that ethics requires a conception of worthiness. A concern and search for what is choice-worthy is the underlying unifying feature of both pre-theoretical orientations.

Unless the agent has some sense of why what everyone is doing is worthy of being done, the conduct is not ethical.

It is not uncommon these days, most especially among those outside of moral theory who speak about ethics, to confuse normatively guided behavior with ethical conduct. A person may follow norms because they are customary, handed down by authorities or tradition. Norms may be arbitrary, selected at random, chosen to maintain someone’s position of power, a response to incentives, or biologically programmed. The conduct exhibited in following norms according to these prescriptive inducements may reflect actions capable of being thought worthy within a framework; but in the absence of worthiness, there is an absence of ethics. For there to be ethical conduct, an action must be recognized by an actor as conforming to or exemplifying a standard thought to be valuable because it represents some principle worthy of exemplification in action. The ethical framework, along with the details of an ethical theory, will describe the nature of any principle of worthiness; but agents can act on such principles without knowing, or even being able to articulate, all the dimensions of the standard of worthiness itself. It is enough that agents see their actions as not simply conforming to or exemplifying a norm, but as being justifiable because the norm it exemplifies is itself justifiable—that is, worthy. Thus, for example, one could follow a norm because “everyone else does.” Yet, unless the agent has some sense of why what everyone is doing is worthy of being done, the conduct is not ethical. The point is the same if we are moved by our biological dispositions to be altruistic or egoistic. Without a recognition of worthiness, a behavior induced by any natural tendencies has all the outward signs of moral action, without actually being such.

Douglas Den Uyl and Douglas Rasmussen

Aristotle noted long ago that for an action to be ethical, it must be chosen, chosen for the right reason, and chosen out of a fixed disposition.

Aristotle noted long ago that for an action to be ethical, it must be chosen, chosen for the right reason, and chosen out of a fixed disposition.[1] One sees in Aristotle’s claim that worthiness gets its meaning from both the notion of worthiness as well as the need for a framework. We have admitted that both the frameworks under consideration here are consistent with the requirement for worthiness. The template of respect, however, insofar as it is concerned with defining relations among persons, has a special task of finding a way to distinguish worthy from unworthy relations among persons, since people can be organized in all sorts of ways that may have little to do with ethical norms. Because relations-among-persons is the defining issue of the template of respect, this framework cannot countenance any norm simply because that norm is interpersonal in nature, or because it defines relations among persons. Instead, there must be a standard which can serve as a basis for calling some relations worthy, while others not. But since actual empirical relations among persons are typically insufficient to serve as the basis for a standard of worthiness—since those may be wrongly motivated or structurally defective—there has been a tendency to rely upon meta-persons, such as noumenal selves, impartial spectators, social utility calculators, appeals to “public reason,” and “views from nowhere” in order to keep within the framework, while still providing a basis for distinguishing the worthy from the unworthy relations. In the template of respect, then, the phenomenal characteristics of the agent and the agent’s relationships are thought to be either irrelevant or insufficient as a basis for determining standards of worthiness. This move is needed precisely in order to subject ordinary human relations to some sort of test of worthiness, which obviously calls for a standard beyond those relations themselves. The basic standard used today to determine worthiness under this template is the degree to which an action impersonally conforms to the dictates of inherent human dignity.

Its central problem is one of deriving norms grounded in our nature, amidst the realities of our circumstances that can serve as independent measures of the actions themselves.

By contrast, the template of responsibility, when looking for standards of worthiness, proceeds from the agent’s own actual actions, character, and circumstances, which are grasped empirically. Its central problem is one of deriving norms grounded in our nature, amidst the realities of our circumstances that can serve as independent measures of the actions themselves. For the moment, we can say—somewhat ironically, given the common notion that teleological arguments impose standards upon the agent—that worthiness is predicated endogenously upon the individual agent’s self in the template of responsibility. For the template of responsibility, it is the agent’s actions or purposes—or, metaphysically stated, the nature of the agent understood in terms of what and who and where the agent is as an individual—that is the ultimate ground for determining standards of worthiness. By “empirical” above, we mean being based on an awareness of the actual character and actions of individuals, as opposed to the application of some rational construct to those actions or character. In essence, then, the template of responsibility is, we believe, quite amenable to an individualistic perspective. In sum, both templates, though quite different in various ways, are alike in positing conditions of worthiness.

It might be argued that reason is also a common characteristic of both frameworks. Only beings with reason can respect one another; and only a being with reason can understand what it means to take responsibility for an action, as opposed to simply following a desire and acting. Indeed, only beings with reason can have a concept of worthiness! So far as it goes, we can say that both these frameworks share in giving reason, in this sense, a central place. However, reason is not like worthiness in its level of fundamentality, if we look to more than what we have just posited. In the template of respect, the relevant properties of reason that tend to get emphasized—for example, universality and neutrality—are not the ones central to the template of responsibility. In the latter case, reason as a cognitive tool for understanding the nature or properties of things is more critical than its formal properties.

We do not mean to conclude, however, that worthiness is the only dimension on which the two templates might find common ground. There may be other dimensions, or perhaps other ways of noting a commonality, that do not appear to be generated by one of the templates alone. Robert Nozick speaks of “being an I,” where having a “special mode of reflexive consciousness which only an I, only a self, has”[2] might be an example of a neutral formulation acceptable to both templates. Here, the deontological associations carried by the term “dignity” are not necessarily directly implied; nor is there a prejudice against forms of naturalism; so, both templates might be able to work with Nozick’s formulation. That is to say, “dignity,” so commonly referenced in much of contemporary ethics, could be easily derived from the foregoing formulation of Nozick’s, as could the teleological naturalism we would advance. Hence, “being an I” could be neutral with respect to both templates.

Perhaps we are best served, then, by looking for a couple of salient differences between the templates as a means to their further clarification. We can begin by considering what is likely to be the ultimate value in each system, and why that would be the case. As we have already noted concerning the template of respect, the foundation for determining worthiness is dignity. If dignity is the basis for worthiness in the template of respect, then its ultimate value is what we shall call “consideration.” To respect dignity, we must give consideration to all those who possess it. A failure to give consideration is the fundamental type of moral failing in the template of respect. We see this reflected today in calls for inclusiveness. Here we need only note that the template of respect allows for the possibility that the mere presence of another person is sufficient in itself to give rise to certain fundamental sorts of moral considerations with a corresponding set of obligations.

But we need not exclude utilitarian theories from this claim about the primacy of consideration. The members of the set of beings for whom our calculations are to maximize value belong to that set because they possess certain qualities that give the appropriate actions their worthiness. A failure of consideration—that is, a failure to consider an agent or factor about the agent relevant to the calculation—would render the calculation itself a failure and thus of no moral worth. Saying that we must be careful about consideration in this utilitarian context is another way of saying that the members of the defined class are dignified within this theory. The basis for dignity could be the possession of certain qualities, such as the ability to feel pleasure and pain; but whatever the basis, consideration must be given to beings which possess the appropriate qualities. Obviously, if pleasure and pain are alone the basis, the question arises as to whether the class of beings to whom one is required to give consideration would include animals, as well. The point is not to argue, one way or the other, over the inclusion of animals in the class of qualified beings, but rather to notice that the utilitarian enterprise must give primacy to the value of consideration in order to even begin to function.

But we need not exclude utilitarian theories from this claim about the primacy of consideration. The members of the set of beings for whom our calculations are to maximize value belong to that set because they possess certain qualities that give the appropriate actions their worthiness. A failure of consideration—that is, a failure to consider an agent or factor about the agent relevant to the calculation—would render the calculation itself a failure and thus of no moral worth. Saying that we must be careful about consideration in this utilitarian context is another way of saying that the members of the defined class are dignified within this theory. The basis for dignity could be the possession of certain qualities, such as the ability to feel pleasure and pain; but whatever the basis, consideration must be given to beings which possess the appropriate qualities. Obviously, if pleasure and pain are alone the basis, the question arises as to whether the class of beings to whom one is required to give consideration would include animals, as well. The point is not to argue, one way or the other, over the inclusion of animals in the class of qualified beings, but rather to notice that the utilitarian enterprise must give primacy to the value of consideration in order to even begin to function.

If the fundamental value of the template of respect is consideration, its fundamental virtue is tolerance or openness. Tolerance, in this sense, encompasses classic willingness to tolerate as well as inclusiveness. To give consideration is to be open to all that must be considered, which is at least a minimal way of understanding what it means to be inclusive. One is continually on guard not to miss considering a qualified candidate for inclusion. And although tolerating doctrines one may disapprove of is not quite complete openness, it is a recognition that the relation is of more importance than the substance of a given doctrine itself. This does not mean tolerance and openness cannot be virtues within the framework of the template of responsibility. It only means that these virtues will tend to be given special emphasis or priority within the template of respect.

For the template of responsibility, the basis for determining worthiness is human flourishing or well-being of some sort. Its ultimate value is integrity. Integrity expresses itself interpersonally in honor; but when applied to the agent herself, the term “integrity” signifies a coherent, integral whole of virtues and values, allowing for consistency between word and deed and for reliability in action. Integrity is probably still the best term to use and represents the central virtue of this framework. For if the fundamental problem of ethics is taking responsibility for figuring out how to fashion one’s life, then a certain coherent picture of what one wants to be immediately reveals the object of the enterprise. Perhaps “honor” is too old-fashioned a term for today’s usage, but it does capture the sense of what it means to greet the world with integrity. Thus, in relationships with others, a person of honor is someone one can count upon to be consistent with her own mode of being, because there is an integrated self that endeavors to maintain the nexus of principles and dispositions with actions that support and express them. Unlike the framework of the template of respect, where what is shared in interpersonal relationships is the common rule or normative command that defines the ethical relationship, what one finds in the template of responsibility is that the ethical relationship cannot be defined prior to the intersection of agents which compose it, since those agents are the basis for defining what the relationship should be.

Besides having different orientations toward their basic values and virtues, our two frameworks also have rather different understandings of the role reason plays in determining the structure of moral norms. We have already examined one role for reason in helping formulate a notion of worthiness. Here we are referring instead to what could be called reason as it affects the structure of a moral judgment. Obviously, such an issue is a complicated business. Here it is enough to note that, contrary to assumptions held by the majority of contemporary ethicists, reason’s structural output in ethics does not cash itself out in only one form. In one way or another, the rational structure of a judgment within the template of respect is caught up in the problem of securing universality. Besides guiding the search for principles that could be universalized according to some standard of formal supervenience (e.g., treat similar cases similarly), universality in the template of respect endeavors to secure judgments that would substantively command the respect of every rational being. There are subtle variations ranging from what every rational being would not reject, to what all would positively command. The object of universality here, however, supposes a substantive like-mindedness on any moral conclusion that qualifies as rational. That is to say, assuming no biases or defectiveness in reasoning, if P1 draws a rational conclusion about the morality of doing action A, then P2-Pn would also need to draw the same conclusion about A. This is as true for the utilitarian as for the traditional deontologist.

In the template of responsibility, by contrast, if P1 draws a rational conclusion about the morality of doing action A, it does not follow that P2-Pn would likewise have to draw the same conclusion under the same circumstances. Hence, an action A which is correct for P1 may not be correct for P2-Pn, even under similar conditions. This result is the case because, under this template, P1 is not substantively interchangeable with P2-Pn, for their particular form of agency is the basis for structuring the moral judgment, rather than serving as an instantiation of one. Moreover, it is also conceivable that judgments made about the correctness of A for P1 might legitimately be different between P2 and P3, and P1 herself. Though it would not be correct to hold that the variation of rational assessments of A is unlimited, the template of responsibility is open to the possibility that there could be a plurality of plausible ethical choices, no one of which is necessarily decisive over others.[3] Though perhaps looking like relativism or situationalism at this stage, such conclusions are not implications of our position. Indeed, we think of ourselves largely as objectivists in ethics. In general, the agent-centered focus of the template of responsibility opens the door to the possibility that the right course of action might differ from one agent to the next, even with respect to their conduct toward others. In addition, that focus also opens the door to the possibility of alternative weightings of principles and actions between agents. Thus, the structure of moral judgments in the template of responsibility is ultimately different in character from that of those in the template of respect, in which actions are typically constrained by some inherent standard of rationality. In the template of responsibility, by contrast, standards of rationality are developed in terms of the agent’s nature, dispositions, circumstances, and abilities, rather than the formal properties of rationality itself.

We do not need to “get to” or “derive” the other in order to begin talking about what one should make of one’s life. Others are already a part of that life, precisely because one is a social animal.

It is, no doubt, the agent-centered nature of the template of responsibility that gives pause to many who reflect on ethics, and precisely because of its being so focused upon the agent. For if the formal properties of rationality are going to be at least partially determinative of the acceptable substantive descriptions of moral conduct, then starting off our theorizing with the self always leaves open the question of how to include the other. Templates of respect want to avoid that problem by making ethics essentially relational. In the template of responsibility, however, assuming the agent is regarded in some essential fashion as a social animal, the presence of the other is already built into the moral landscape. We do not need to “get to” or “derive” the other in order to begin talking about what one should make of one’s life. Others are already a part of that life, precisely because one is a social animal. [4]

There is another way in which the rationality features of the two templates may affect the degree of satisfaction theorists come to expect from them. If the template of respect is wedded to some of the formal properties of rationality in its structuring of moral judgments, it will be less satisfied with ambiguity and open-endedness than an approach that does not have such strictures. In essence, the template of respect tends to look at the job of moral theory as being one of providing answers to the question of what we morally must do. In the template of responsibility, however, it is possible to hold that the job of moral theory is not to provide answers about what must be done, but rather to provide aid in the form of principles and insights, on the basis of which individuals can fashion conclusions for themselves according to their circumstances. Although we would not want to claim that the template of responsibility requires this degree of openness to ambiguity and radical pluralism, it is instructive of the nature of this approach to ethics that the responsibility template can be comfortable with such openness. In this respect, the template of responsibility is significantly less “rationalistic” than is the template of respect. Its judgments are meant to fit patterns of actual practice, rather than to encourage a formal structure, as would be the tendency under the template of respect. As such, its form of rationality would be along the lines of the realism hinted at above, rather than a more formal rationalism. In this respect, as we have also suggested, ethical norms of universal applicability are not necessarily of a superior or more fundamental status in the template of responsibility, as they would be within the template of respect.

The rationalism of the template of respect no doubt dominates the modalities of ethical theorizing today in ways that obscure possible alternative modes of understanding the functionality of ethics in social life. The tendency toward universalism and law-like pronouncements in the template of respect encourages the view that ethics is a tool of social control and one that trumps all other candidates in cases of conflict. “A is wrong” is sufficient in itself to disallow consideration of any alternative reason for doing A; and “A is right” is sufficient in itself to require doing A. On this model, ethics is both a necessary and sufficient reason for taking or avoiding any action; and if it is not the sole regulator of action, all other candidates are at least in need of permission from ethics for doing so. Consequently, ethics within the template of respect organizes patterns of consistent behavior among diverse actors along the lines dictated by the normative rules derived from the ethical theory. In short, ethics becomes the principal vehicle by which to command or create social order. In the template of responsibility, however, one would expect the socially organizing norms of ethics as universally applied to be few and functionally limited. Social coordination would be predicated more upon cooperation than upon conformity to a standard; and such normative standards as do exist would as likely be descriptions of modes of cooperation or practices, as they would be the basis for imposing such order. Consequently, the template of responsibility sees ethics not so much as the means of defining relations among persons, but more as a tool for guiding and regulating the interests and purposes of agents as they search for shared reasons to interact. Cooperation is more the epigraph for the template of responsibility, which holds accommodation and mutual interest as the basis of social relations. For the template of respect, by contrast, obligation is more the epigraph and duty the basis for cementing social unity.

From our perspective, then, we would say that the template of respect issues forth ethical doctrines that wield the sword of righteousness, whereas the template of responsibility yields doctrines more dependent upon the exercise of discipline. If so, the social outlook of the template of responsibility will be one of finding ways to enhance the forms of cooperation that have been created whereas, under the template of respect, the prospect is one of either defining the forms of social interaction themselves, or reforming the ones that exist, in order to meet the required standards of conduct.

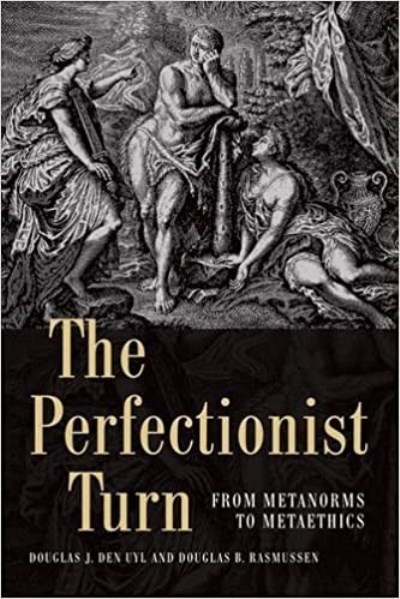

It is clear from all that we have said that the turn we wish to make is toward the template of responsibility and some sort of perfectionist theory falling under its rubric. In this regard, we offer four structural pillars for our particular approach within the template of responsibility. These pillars follow the four structural characteristics Julia Annas uses to describe ancient ethics.[5] The first of these is that the object of ethics and the standard for measuring ethical conduct center around the agent having a final end that is a good for that agent. Secondly, that final end is not a good like other goods, even those pursued for their own sake, but a way of organizing the other goods. Thirdly, the final good is concerned with one’s life as a whole, and not simply with parts of one’s life. And finally, the final good does have objective properties and some formal constraints.[6] With these points in mind we encourage reflection on ethics to make “the perfectionist turn.”

*Virtually all of this essay is taken from “Introduction: What is Ethics?” in Douglas J. Den Uyl and Douglas B. Rasmussen, The Perfectionist Turn: From Metanorms to Metaethics (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), pp. 1 – 26. It is reproduced with the permission of Edinburgh University Press.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1]Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, 1105a 31 – 33.

[2]Nozick, Philosophical Explanations (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, Harvard University, 1983), p. 453.

[3]Indeed, while what we call “metanorms” (which is the concept we develop in Rasmussen and Den Uyl, NOL to explain the exact character of individual rights) might be candidates for such norms, they are to our minds of lesser moral significance than conclusions which are not so. decisively universal. Still, we do not wish to exclude from the template of responsibility a theory which holds that P1-Pn would have to draw the same conclusion. It is just that, in this template, that conclusion would not be required by the nature of reason itself.

[4]We argue in Rasmussen and Den Uyl, NOL, pp. 20 – 21 that individualism is not atomism.

[5]Julia Annas, The Morality of Happiness, pp. 34 – 45.

[6]Annas notes that in Aristotle, two of the formal constraints were completeness and self-sufficiency, the later often being dropped by later philosophers (ibid., pp. 40 – 3).