“Sully”: Another Movie Opts for Real Life, Then Fights It

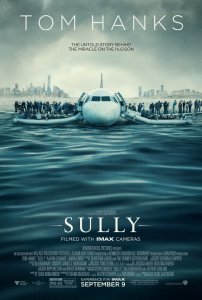

If you know the story (who doesn’t?) of U.S. Airways Flight 1549, departing LaGuardia Airport on January 15, 2009, then forced into a crash landing into the frigid Hudson River—a landing that all 155 aboard incredibly survived unharmed—you well might wonder why this review needs a “spoiler alert.” Who doesn’t know the heroic outcome?

All of them [some recent movies about real-life dramas] struggled with the temptation to take advantage of the built-in audience for great events, historic or contemporary, and with the natural (or corrupting?) temptation to add fiction to truth to enhance drama and—some more, some less—to score points for an ideology.

No one had ever survived the forced landing of a commercial jet on water, a factoid that used to cause my son and me to burst into nervous giggles when airline attendants gravely reviewed directions in event of a water “landing.” It was literally incredible that Capt. Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger brought down the Airbus A320 jet with no thrust in either engine (the moment the plane collides with the flight of Canada geese is terrifying) and got every single passenger—elderly, baby at breast, disabled—off the plane, onto the life rafts or plane wing, and then onto the rescue boats.

You are going to have to overlook some personal asides by a reviewer who has run (lately walked) hundreds of times along the Hudson River where Flight 1549 went down. New York Waterways has been a fixture around Manhattan for decades, its big ferries circumnavigating the island with sightseers, ferrying commuters to ports in Brooklyn or New Jersey. The capacious blue and white ferries were hardly designed for sea rescue. But when Flight 1549 went down in the Hudson, in sub-zero weather—with the biggest threat to passengers huddling on rafts, on the plane’s wings, or floating in the water—the first three vessels to reach the ship and begin rescue operations were the New York Waterways ferries. They safely landed passengers in Manhattan and New Jersey, whose faces seemed literally aglow with the wonder of resurrection. That was not the first scene in the film that brought tears.

So why a spoiler alert? Captain Sully (Tom Hanks) and First Officer Jeffrey Skiles (Aaron Eckhart) became heroes in a way that only New York can create and honor them. That the plane crashed, that it was terrifying, that the rescue was dramatic and heart-warming: We know it all.

And that, of course, is the dilemma of the real-life drama. As I think back to my review of recent movies that became competitors at the Academy Awards, the “real-life” dramas seem to predominate: “The Revenant,” “The Big Cover-Up,” “The Imitation Game.” All of them struggled with the temptation to take advantage of the built-in audience for great events, historic or contemporary, and with the natural (or corrupting?) temptation to add fiction to truth to enhance drama and—some more, some less—to score points for an ideology.

The decision in “Sully” is to fictionalize a part of the story barely mentioned in Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters, Sullenberger’s account of the incident: the inevitable investigation of the accident by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). That is the drama that begins and ends the movie, sandwiching the superbly well-done, moving portrayal of the forced landing and rescue. It is this drama that supplies the indispensable suspense, the drawn-out fear, hope, and pain of the movie. It certainly works. Writer Todd Komarnicki (who recently died in a car crash) and Clint Eastwood win an agonizing empathy for Sully, his first officer, and his wife, and find a way to give the announcement of the NTSB team all the riveting conflict of the McCarthy hearings.

The decision in “Sully” is to fictionalize a part of the story barely mentioned in Highest Duty: My Search for What Really Matters, Sullenberger’s account of the incident: the inevitable investigation of the accident by the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). That is the drama that begins and ends the movie, sandwiching the superbly well-done, moving portrayal of the forced landing and rescue. It is this drama that supplies the indispensable suspense, the drawn-out fear, hope, and pain of the movie. It certainly works. Writer Todd Komarnicki (who recently died in a car crash) and Clint Eastwood win an agonizing empathy for Sully, his first officer, and his wife, and find a way to give the announcement of the NTSB team all the riveting conflict of the McCarthy hearings.

The NTSB, of course, conducted the legally mandated and inevitable inquiry into the causes of the crash, including calling Sully and his first officer to testify. In the movie, this inquiry is portrayed as a heartless Inquisition, adversarial from that start, by classic bureaucratic villains. What is at stake? In the aftermath of the crash, Sully became, as he did in real life and still is, a hero, cheered by the White House, across the media, by crowds everywhere he went, and in bars (as he discovers) everywhere in the city. What if the NTSB reached the conclusion that Sully, far from a hero, reached a potentially disastrous decision to crash in the Hudson when the damaged aircraft could be shown in computer simulations capable of returning to LaGuardia for a nail-biting but “normal” landing? What if the crash is declared “serious pilot error”? Then, Sully’s mastery of flying did not miraculously save 155 people; his panicked, unwarranted judgment put them through hell. Makes a difference.

This becomes the explosive charge of the crash story, threatening to blow up everything, that makes us ache for Sully, sequestered from his family in hotels while the NTSB inquiry goes on, jogging through streets of midnight Manhattan to preserve his sanity. The movie, in this way, is skillfully elevated into a first-rate suspense story, a momentum that keeps us identified to the very end with the crisis in Sully’s life.

The NTSB, of course, conducted the legally mandated and inevitable inquiry into the causes of the crash, including calling Sully and his first officer to testify. In the movie, this inquiry is portrayed as a heartless Inquisition, adversarial from that start, by classic bureaucratic villains.

Sully is an inspiring movie about what the reviewers are calling a “real-life hero,” and an “everyday hero.” And that seems to be the attitude of the real Sullenberger. But he is no such thing. He is a type of man, an especially well-known American type, in love from an early age with aviation. He was a brilliant, high-achieving student in a small Texas town who earned appointment to the Air Force Academy, and, there and later, had experience with almost every conceivable variety of aircraft under every condition around the world. Sully was a man with a passion for the highest achievement in the field he loved.

Another aside: I had occasion to interview flight school trainers in the course of a writing assignment, and a definite contingent of them were passionate about the importance of glider training. They felt that many terrible crashes of commercial airliners might have been saved by pilots steeped in handling engineless gliders. Even a brief account of Sully’s Air Force training and experience indicates a specialty in glider flight.

Did Sully’s impassioned pursuit of his best, decade after decade, including thousands of flights as a commercial pilot, make possible a heroic achievement that day in January in command of an aircraft that if the wrong choice had been made could have slammed into the heart of New York City and exploded in a fireball? Or blown up in the Hudson with all lives lost as was thought inevitable in such situations?

Eastwood, in an interview, took the direct approach to justifying the portrayal of the NTSB as inquisitors displaying not a shred of feeling for what Sully had experienced and achieved. He argued that it was true: The goal of the inquiry had been to assign blame to Sully. The movie’s bad guys are soulless bureaucrats, regulators, running their computer simulations with never a nod to the “human factor.”

The NTSB officially protested this view; the head of the inquiry denied any intention to “hose” the crew; and the truth is that a heart-stopping moment in the drama, when Sully demands that the damning computer simulations of the accident be rerun to include the “human factor” of time for decision making—simply never happened. The real Sully demanded that the film not use the actual names of the NTSB team. The left-leaning British daily, The Guardian, sneered that it was so predictable that the “libertarian” Eastwood chose to portray government regulators of the NTSB as villains. This was going to set back the work of preventing future crashes.

To give Sully the last word: He emailed, in response to a New York Times inquiry, “that the tension in the film accurately reflected his state of mind at the time. ‘For those who are the focus of the investigation, the intensity of it is immense,’ he said, adding that the process was ‘inherently adversarial, with professional reputations absolutely in the balance.’”

This is where the morality of attracting audiences by using the names of real individuals involved in real events, and then perhaps deceiving the audience about the character of those individuals, is on trial. The now-retired leader of the inquiry portrayed in “Sully,” Robert Benzon, told the same Times reporter: “Sully is worried about his reputation, but this movie isn’t helping mine.”

This is where the morality of attracting audiences by using the names of real individuals involved in real events, and then perhaps deceiving the audience about the character of those individuals, is on trial.

Benzon has a reputation to uphold. After flying combat missions over Vietnam, he joined the NTSB in 1984 and during a 30-year career has been leader of some 100 inquiries into aviation disasters famous—the American Airlines Flight 587 crash into a Queens neighborhood in in 2001 killing more than 250 people—and less well-known. Each such investigation involves hot pursuit of hundreds of pieces of evidence from crew interviews to flight recorders to engine damage to interviews with aircraft manufacturers—all under intense political pressure. “Bob is the calm in the midst of a storm. He’s steady, reliable and the rock,” said NTSB Chairman Deborah Hersman. “In accident investigations, that’s exactly what you need.”

Benzon is credited with having in effect “written the manual” on investigation of aviation disasters. Revelations repeatedly have emerged about the causes and prevention of crashes, leading to pointed recommendations to airlines, pilots, and the aircraft industry. Benzon’s reputation has made him the man to call for crash inquires not only at home but in Afghanistan, Scotland, Borneo, and China. He was the inevitable choice for the unprecedented forced landing of Flight 1549.

Unlike “The Imitation Game,” which, apparently (and wholly unnecessarily) to glamorize homosexuality, played fast and loose with the reputation of a World War II hero now dead, “Sully” puts in play the reputation of a man who will be going to the theater any day now to see himself “defeated” by the “good guys.”

« Private or Public Police—a Case Study in Prevention versus “Cure” How to Actually Fight Terrorism—In Six Simple Steps »