Translating deep thinking into common sense

The Surest Way to Overthrow Capitalism

By Keith Weiner

January 10, 2019

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

If business managers can’t tell the difference between a wealth-creating or wealth-destroying activity, then our whole society will be miserably poor.

One of the most important problems in economics is: How do we know if an enterprise is creating or destroying wealth? The line between the two is objective, black and white. It should be clear that if business managers can’t tell the difference between a wealth-creating or wealth-destroying activity, then our whole society will be miserably poor.

Any manager will tell you that it’s easy. Just look at the profit and loss statement. Profit is so powerful an incentive for managers, that one could never persuade them to operate based on any other indicator. And it would work—if economists had done their jobs properly.

But have they?

As we have argued many times, economists have given their apologia for the regime of irredeemable currency. Millions of trees have sacrificed their lives, so that economists could print their books and papers arguing in favor of debasement to promote employment, debasement to promote exports, debasement to boost GDP, and debasement in a crisis.

It reminds us of the old Steve Martin comedy routine, where he said he only smoked marijuana in the late evening. As he went on and on, he added more and more times when he would smoke it. In the end, he conceded, well, at least he didn’t smoke pot at dusk.

As you can imagine all this debasement causes a problem for anyone who tries to use the dollar as a unit of measure. So economists have proposed a solution. They adjust the dollar.

Like physicists who assume that pulleys are frictionless and massless, only with less realism, they assume that consumer prices would be constant but for the relentless debauchery of the central bank. So they use consumer prices to adjust the dollar.

Prices are measured in dollars, which are adjusted using prices. If this seems circular, well, it is.

There are many problems with developing a consumer price index. First is what to include. A 20-year old may not care much about the cost of health care, but if he drives a muscle car, he may care a lot about the price of gas. A professional who lives in the central business district may not drive, but the majority of his income goes to pay rent.

But assume that, somehow, economists agree on the right items to include in the basket, and this basket can somehow determine monetary debasement. For example, they add apples, oranges, gasoline, and fuel. Never mind what Mrs. Lowell said in fourth-grade-math class. You absolutely can add apples and oranges! The license to commit this crime against mathematics is granted with one’s PhD in Economics.

Anyway, next come the so-called hedonic adjustments. Sure, the argument goes, a car in 2019 is more expensive than a car was in prior years. But the car today has a gazillion air bags, a satellite navigation system, and Bluetooth. So the price is somehow adjusted for these extra features.

We would call the consumer price index a farce, but we would not want to be unkind to Monty Python. If you are getting a picture of pseudoscience, that’s it. The adjusted dollar gives all the appearances of providing a reliable measure of value, the way Hollywood gives all the appearances of a battle in space. We have news for you, Star Trek physics isn’t real.

So the net result is that the mostly-falling but sometimes-rising dollar (i.e. debasement with volatility) is pronounced “fit for purpose.” All businesses may be managed by profit and loss statements, based on the dollar as numeraire. Never mind that Keynes and Lenin saw it clearly in 1922: debauching the money impoverishes everyone generally, but enriches a few (who are hated by the others, as their enrichment is arbitrary and unjust). Today’s otherwise-free-market advocates (other than in money and credit) don’t understand what debasement with volatility does as well as did those (evil) geniuses.

Keynes and Lenin said, “There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency.”

Otherwise-free-marketers provide cover. They say that the dollar must be adjusted, but of course the dollar used on every profit and loss statement is not adjusted. If a business spends $900 and earns $1,000, then it has a profit of $100. There is no incentive to adjust the $1,000 revenue downward or the $900 expense upward. There is no way for the business manager to even know if this unadjusted profit is illusory.

If it is illusory, then that means the enterprise is destroying wealth. But if there is a profit, then that means managers will be rewarded for a job well done, with bonuses. And the enterprise will obtain more resources, and hire more people to scale up. To accelerate its destruction of wealth.

Unlike the problem of rising consumer prices per se, this problem can wipe out a civilization if it is allowed to grow big enough.

There is another way that our failing monetary system causes enterprises to destroy wealth, which is separate from the unstable unit of account we describe above.

Think of how a manager makes a decision whether or not to grow a business line, or develop a new one. He adds up all the costs. And then compares the total to the estimated revenues. It’s pretty simple. To grow the line, estimated revenues must exceed estimated expenses.

The interest on borrowed capital is a significant expense. This expense decreases every time the interest rate falls. In our mad regime of irredeemable currency, the trend has been to fall since 1981 (corrections, like the one most-likely just finished, notwithstanding).

Could King Canute make the tide go out? Can Congress pass a law to set the speed of light at 3 X 10^7 meters per second? Can the central bank really turn a wealth-destroying activity into a wealth-creating activity?

No, of course not. They can only force you to behave as if reality is other than what it is. They can distort your perception, as we wrote two weeks ago.

When the interest rate drops, that does not turn a wealth-destroying activity into a wealth-creating one. Obviously. However, it can make such activity appear to be wealth-creating.

When the interest rate drops, that does not turn a wealth-destroying activity into a wealth-creating one. Obviously. However, it can make such activity appear to be wealth-creating.

Think about that. Take as long as you need. If you understand this, you understand more than 99% of economists.

An activity, which you can see destroys wealth in black and white, suddenly becomes wealth-creating. Simply by a drop in interest rates. For example, at 8% interest the expense of borrowing $1,000,000 is $80,000 a year. If the activity only generates $75,000 in gross profit, then you lose $5,000 a year. But if the interest rate is cut in half, now you pay only $40,000 a year in interest. But the gross profit remains the same $75,000. Now it looks attractive because instead of losing $5,000 you make $35,000 a year. So you borrow the $1,000,000 and expand the business.

As an aside, each time the rate is lowered, it’s not just you who borrows to expand production. It’s everyone else, too. So you take on $1,000,000 in debt and annual interest expense of $40,000 to chase $75,000 profit. But you find it’s more like $50,000 because more suppliers enter the market.

Our key point is that the rate of interest moves the line between what is profitable and what is not. If the rate is too high, then some wealth-creating activities will not be financed. Society is poorer than it should be.

If interest is too low, then some wealth-destroying activities are financed. Destruction is profitable, and so it scales up. Society itself is doomed.

What is the right rate of interest? We can define it in general terms. The right rate is the rate where the marginal borrower is creating wealth.

And how is the right rate determined and set? Forget everything that the otherwise-free-marketers say about this. There is no way for a central planner to know the right rate. And no good way to set it, even if he did know it, without wreaking other havoc.

The rate has to be set in a free market. That means the unadulterated gold standard, which is free not only from the central planning of central banks but from all other government distortions, such as forcing banks to load up on government bonds.

In a future article, we will expand on why these two statements are true principles: (1) there is no way a central planner could set the right rate, even if he knew what it would be, and (2) only a free market can know the right rate.

Supply and Demand Fundamentals

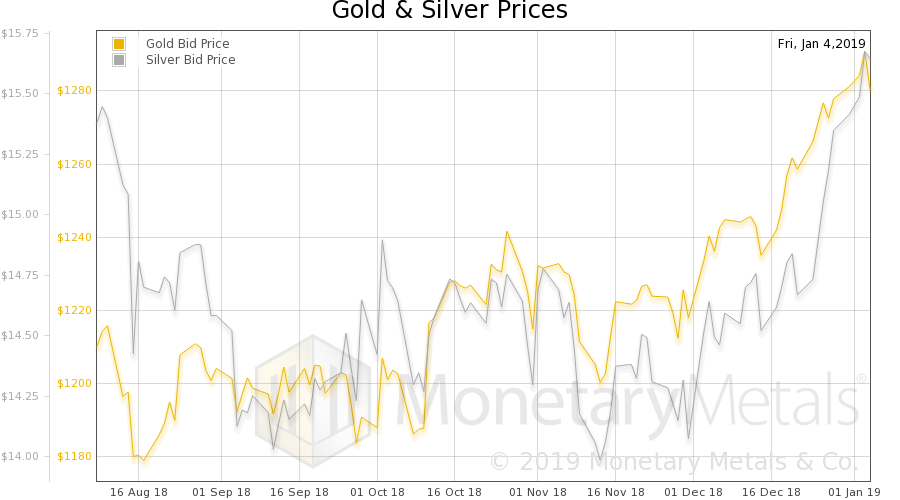

The price of gold went up four bucks, and the price of silver rose 32 cents. Silver has been going up in gold terms since the middle of last week, when the gold-silver ratio peaked at just under 87. It closed this week at just under 82 (a lower ratio means silver is more valuable). 87 is quite an extreme level. So it’s natural for there to be a move back down. But is this move durable, and likely to continue?

We will look at that when we discuss silver’s supply and demand charts.

Let’s look at that picture. But, first, here is the chart of the prices of gold and silver.

Next, this is a graph of the gold price measured in silver, otherwise known as the gold to silver ratio (see here for an explanation of bid and offer prices for the ratio). It fell sharply again this week.

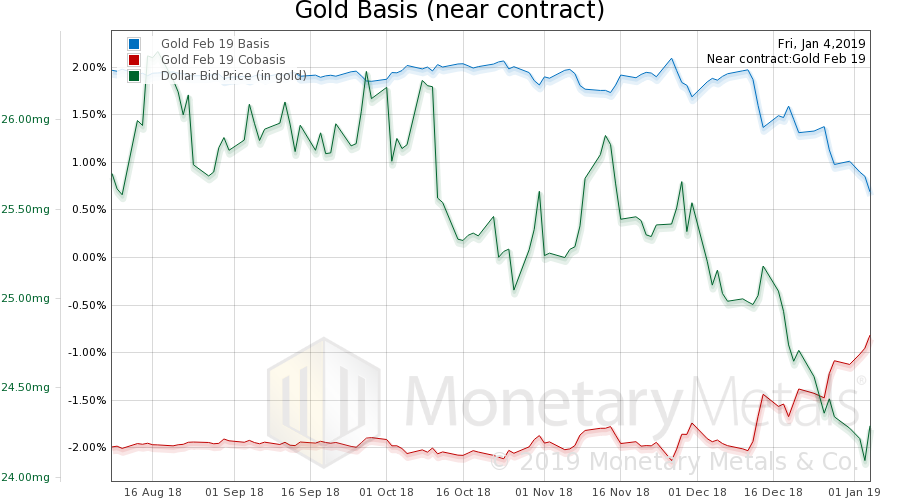

Here is the gold graph showing gold basis, cobasis and the price of the dollar in terms of gold price.

Keep in mind that this is the February contract, which is under selling-pressure as it approaches expiry. The gold continuous basis is basically flat. So this week, no real price move and no real supply and demand move.

The Monetary Metals Gold Fundamental Price fell back $4 to $1,321, so no real fundamental move either.

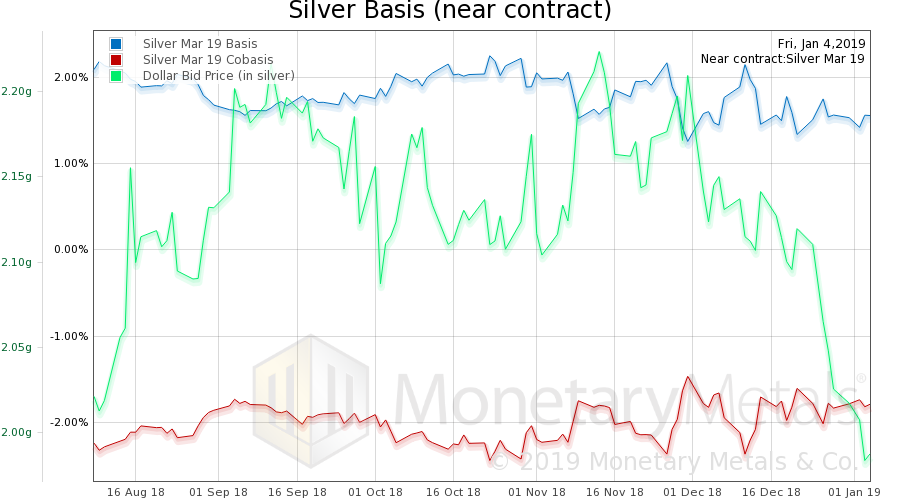

Now let’s look at silver.

As the price of silver rose over 2% this week, the cobasis basically held steady. There is some buying of metal here, and some speculation too. This is not exactly the picture of a feeding frenzy, with an outlook of silver-to-da-moon. But nor is it a sign of a speculative blip, with a prognosis of a crash.

The Monetary Metals Silver Fundamental Price rose 12 cents, to $15.91.

This week, of course, the stock market went up. Does the incredible bull market roar back to life? We are not stock market prognosticators, but we don’t think so if the Fed stays the course. The discount on future earnings is higher now and therefore the present value is lower. Also, the interest expense is up and this will crush the marginal debtors.

The biggest up-day in the stock market occurred when Fed Chairman Jay Powell said the Fed is “listening to markets.” So stock market speculators believe that the Fed will change its policy, or at least mitigate its policy to serve a real or imagined third mandate—a rising stock market?

We think that the market is past the point where mere jawboning will work. So if the Fed changes nothing, then eventually higher rates will convert into a higher discount rate and hence lower stock prices. And not just lower stock prices, but defaults from marginal debtors big and small. Stresses on balance sheets big and small. Underfunded pensions coming back to the fore. Etc.

In short, that would not be an environment of rising trust in the banks. More likely, an environment of a rising cobasis, and maybe backwardation. We haven’t seen this in quite some time.

Alternatively, the Fed can reverse course and lower interest rates. The way a 5-year-old child, first learning to play chess, will move a bishop too far and then waste a move pulling it back. Not a way to develop credibility (though we must point out that the dollar does not depend on credibility per se).

In an environment of the Fed saying it will drop rates to accommodate the stock market, we might get a return to the halcyon days of 2009-2011.

So we cautiously take the position that the prices of the metals are likely to rise from here.

One thing is for sure, it’s not curtains for the dollar or America. That day will come, but to fall back to our favorite quote from our favorite movie character, Aragorn, “today is not that day.”