Translating deep thinking into common sense

Will Sovereign Defaults Trigger the Next Financial Crisis?

By Vinay Kolhatkar

July 23, 2018

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

“Countries don’t go bankrupt.” Walter Wriston, former head of Citibank

“There is a myth that floated around the banking community not many years ago that governments do not go bankrupt. I cannot imagine who dreamed that one up.” Gordon Tullock, Economist[i]

Wriston’s quote is astonishing, given that, according to MIT Press, “The first recorded default goes back at least to the fourth century B.C., when ten out of thirteen Greek municipalities … defaulted on loans from the Delos Temple.” MIT Press also details sovereign debt restructures from 1820 onwards, and there hasn’t been a continent on earth or a long-enough period without one.

In recent times, such defaults have been witnessed for Russia, Argentina, Ecuador, Greece, Iraq, Uruguay, and many others, with investors taking ‘haircuts’—a cutback in the principal amount repaid—some ranging from 50% (Russia) to nearly 90% (Iraq).

But only fixed-interest investors need worry about banana republics not paying them back, right? Think again. We are entering uncharted investment waters—a world in which great republics may repudiate their sovereign debt, setting off a chain of catastrophic corrections.

Expensive haircuts those, but for what is purportedly a low-risk asset class, investors flock back again with renewed vigor: “This time, it will be different.” So said Argentina. Argentina, the uncrowned king of defaults, had, by some estimates, defaulted eight times on its sovereign debt, the last in 2014. In 2016, it borrowed yet again. Then, in 2017, jaws dropped as it managed to sell $2.75 billion of bonds at 7.9% (in US$) on a 100-year maturity, and then, with inflation running at 40% per annum, and the peso falling, sought IMF assistance in May 2018.

Perhaps some money managers are so hungry for yield today, that the risk of haircuts tomorrow is underplayed.

But only fixed-interest investors need worry about banana republics not paying them back, right? Think again. We are entering uncharted investment waters—a world in which great republics may repudiate their sovereign debt, setting off a chain of catastrophic corrections. And the greatest republic is the United States.

Will the USS Titanic Hit the Iceberg in 2028? Or Earlier?

When the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its ten-year budget and economic outlook in April 2018, it reported that: “The budget deficit will near one trillion dollars next year, after which permanent trillion-dollar deficits will emerge and continue indefinitely.” The national debt, CBO said, “… is rising unsustainably.”

However, several economists have long argued that even the CBO vastly understates the problem.

Boston University Economics Professor Laurence Kotlikoff, contends that CBO’s debt estimates do not take into account the full financial obligations the government is committed to honor, especially for future payments of Social Security, Medicare, and interest on the debt. That “fiscal gap,” according to Kotlikoff, a net present value (NPV) of future obligations (written into current law) less expected revenues is well over $200 trillion. In 2017, U.S. GDP was $19.4 trillion.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) also has a more pessimistic opinion than the CBO. The IMF’s view is that by 2023, the US debt-to-GDP ratio could be on par with Italy’s, both well over 100%.

Audits of Sovereigns

We justly require an independent financial audit of our corporations. Sovereigns should be subject to a similar discipline, with auditors chosen by a lower house majority and affirmed by the upper house (in democracies).

The vast majority of sovereigns are incessantly running budget deficits. Many may have liabilities in excess of assets. The power to tax is an asset. However, it’s constrained by ‘Laffer-Curve’ realities: Taxation revenue falls when tax rates become too high—due to evasion, reduced incentive to work, and economic deterioration.

If auditors applied the same tests to sovereigns as they do to corporations, many sovereigns may not pass the test of solvency.

If auditors applied the same tests to sovereigns as they do to corporations, many sovereigns may not pass the test of solvency.

Indeed, the Bureau of the Fiscal Service (BFS), a U.S. government agency, provides accounting services to government. BFS says that, at 30 September 2017, the U.S. Government’s liabilities exceeded its assets by $20 trillion.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), an independent, nonpartisan agency that works for Congress, warns:

“… policymakers will need to consider policy changes to the entire range of federal activities, both revenue and spending (entitlement programs, other mandatory spending, and discretionary spending).”

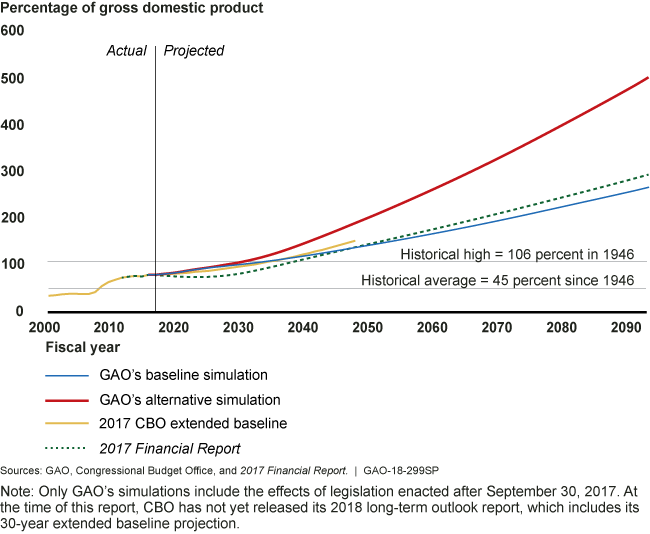

The chart below compares the GAO, CBO, and BFS projections for a debt (held by the public)-to-GDP ratio.

Source: GAO

The U.S. is Not Alone … The Rumblings in Europe and Asia

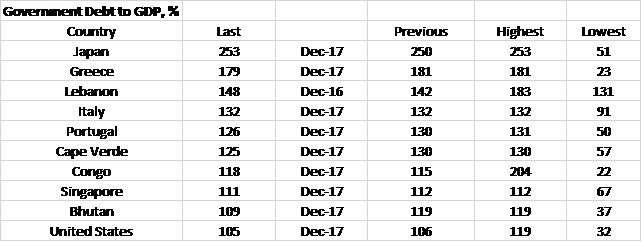

Trading Economics produces a Debt/ GDP ratio table by country. Here are the 10 worst ones:

Unsurprisingly, the worst offenders are trading at or close to their highest-ever ratios.

Meanwhile, here is Forbes magazine on the top offender, Japan, December 2017: “By 2041, assuming tax revenue remains constant and there won’t be any economic shocks, Japan’s interest repayments will exceed tax income. Note that we also assume [the] interest rate to stay at 1.1%, because if this figure increases then the government will default more quickly.”

And here’s the IMF (January 2018) on China:

“International experience suggests that China’s current credit trajectory is dangerous with increasing risks of a disruptive adjustment and/or a marked growth slowdown … A disorderly correction from such an expansion could have far-reaching implications on financial stability and growth.”

Worse, at least some of the public spending in China that bolsters GDP artificially has been financing the construction of ghost cities.

In Italy, the current focus of consternation in the Eurozone, all the main political parties are promising sweeping tax cuts, higher public pensions and a boost in welfare provisions. With a straight face, the politicians also say they will cut the national debt at the same time, in a Don Corleone “we will make them an offer they can’t refuse” style. Voters agree, but not Roberto Perotti, an economics professor at Milan’s Bocconi University, who cried out: “They are just trying to trick us, they are throwing out random numbers that make no sense.”

Kicking the Can down the Road

The Italian experience sums up the political response in fiat money economies perfectly.

To suggest raising taxes or cutting welfare is the surest recipe for removal from office.

Borrowing from the next generation, as long as capital markets allow, is one way to kick the can down the road. The nation’s banks must hold sovereign bonds as liquid, ‘low-risk’ assets by regulation. The central bank reduces interest rates because the Keynesians think that’s stimulatory.

Borrowing from the next generation, as long as capital markets allow, is one way to kick the can down the road. The nation’s banks must hold sovereign bonds as liquid, ‘low-risk’ assets by regulation. The central bank reduces interest rates because the Keynesians think that’s stimulatory. Yet they have been near-zero in many advanced economies, after non-stop diminution for 30 years.

Saving rates plummet, but the yearly interest bill is low, courtesy low rates, and principal repayments and ongoing deficits are managed by ever more borrowing. When the markets do not buy enough, the central bank itself starts buying—sovereign bonds at first, then mortgage assets, corporate bonds, equities … whatever is required to keep the markets afloat.

Austerity, Theft, or Repudiation?

A debt feast of that nature does not end until markets force it to, or when even interest payments cannot be met. By this point, the austerity (cuts in welfare) required is so high that it’s politically unmanageable.

Theft is an option for central banks who have been stealing from savers for decades. The currency can be debased totally. Large-scale money printing to repay creditors in nominal terms is termed as the Zimbabwe option, where, in 2008, inflation peaked at a daily rate of 98%. Hyperinflation destroys many innocent citizens financially, and crucifies the economy.

Repudiation is the better course of action, which does not destroy the currency or the economy, but hurts those who bought the bonds in the first place. However, besieged countries may choose a bit of everything: a little austerity, high inflation, and an offer of an expensive haircut.

Repudiation is the better course of action, which does not destroy the currency or the economy, but hurts those who bought the bonds in the first place. However, besieged countries may choose a bit of everything: a little austerity, high inflation, and an offer of an expensive haircut.

In the 2012 presidential primaries, then Congressman and candidate Ron Paul advocated that the U.S. should repudiate its debt. In the 2016 primaries, Donald Trump publicly speculated a scenario giving bond investors a 50% haircut after becoming the presumptive nominee, but then retraced when warned of the near-term ramifications.

When the Rescuers Need Rescuing

Relentless Quantitative Easing has created some $13 trillion of assets across the U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BoJ), plus several trillion more from other major central banks. As equity underwriters to an IPO who are stuck with a lot of stock know, a large overhang that stands at ‘ready to offload’ creates a price ceiling. The Fed’s assets are now 23% of GDP, a level nowhere near seen since just post WWII, while BoJ’s assets are over 50% of GDP.

In Europe, we may see no one on the pier, hauling the drowning out. A more likely scenario is a circle of sovereigns (and their central banks) holding hands, each assuring the one on their left, “No worries, I’ve got you, mate,” as market currents push them all out to sea.

Between them, the Fed, the Bank of England (BoE), ECB, BoJ, and other central banks have bought not only their own sovereign bonds and financed their government’s deficit, but also other sovereign bonds, mortgage securities, asset-backed securities, corporate bonds, and even outright listed corporate equity.

European banks hold other European sovereign risk to a significant degree. They intertwine and entangle their fortunes. In Europe, we may see no one on the pier, hauling the drowning out. A more likely scenario is a circle of sovereigns (and their central banks) holding hands, each assuring the one on their left, “No worries, I’ve got you, mate,” as market currents push them all out to sea.

Can One Insure against Black Swan Events?

When things turn that sour, prices drop everywhere—stock markets, real estate, bonds. Downside correlations among asset classes can be much higher than upside correlations. Global fixed-interest manager PIMCO opines that activist central banks make for stronger correlations across asset classes. In Black Swan events, such asset classes could be as together as Jack and Jill tumbling down the hill. We know that from the 2008 financial crisis.

Even worse, governments everywhere will be forced to reduce pensions in real terms just when retirement nest-eggs take a big hit.

Wholesale investors could seek insurance via customized strategies such as inverse trades, which profit when markets go down. Some investors may prefer physical gold, gold ETFs, or long volatility trades (positions which profit from higher market swings). Such insurance involves ongoing opportunity costs and risks. A comparison of the risks, costs, and strategies of such investment insurance policies is beyond the scope of this paper.

The year 2029 will mark the centennial anniversary of the Great Depression. It’s not just a bad omen, the fundamentals point to a severe correction, which is hard to insure against.

This article has been written purely for educational purposes, and is not intended to be financial advice. A shorter version of this essay appeared in the Australian financial newsletter, Cuffelinks, on July 18, 2018 with the title: Will sovereign defaults spark the next GFC?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[i] Source: The Independent Review, v. 18, n. 4, Spring 2014, ISSN 1086–1653.

The United States Government can no more run out of dollars than a bowling alley can run out of strikes.

Printing money to repay creditors is not a solution. It’s worse than cutting spending or not repaying them.

Not necessarily. In today’s economy, it makes more sense to issue “unbacked” fiat money to fund the deficit than to go further into debt. The inflationary impact of new unbacked dollars would be no worse than the inflationary impact of the same amount of new debt-backed dollars.

Debt-free money would allow us to slowly pay down the national debt without a lengthy, unpopular and economically damaging austerity program. Debt-free money would not saddle future generations with unchosen obligations; the inflationary consequences would be immediate, and would act as an incentive to cut spending now rather than a few generations from now. Debt-free money would help shift monetary control from the Federal Reserve back to Congress.

Issuing unbacked dollars would halt the increase in the national debt and its crushing $430 billion in annual interest. Paying off part of the maturing debt each year and rolling over the rest would eventually bring the national debt (and its taxpayer-financed interest payments) down to zero.

Debt-free fiat money is far from perfect, but it is vastly superior to the debt-based monetary system we have now.

But inflation hurts randomly. It is just and proper to hurt only those who were stupid enough to buy the bonds so the market learns the lesson once and for all, and the very idea of sovereign debt disappears from the planet for good.

That would be a good topic for a future discussion. In the

meantime, given that fiat money is with us for the foreseeable future, should

the government continue funding its deficits by issuing bonds or not?

With debt-free money, the answer to this question is “not”, and many serious

moral issues do not arise. Debt-free money does not burden future generations

with unchosen obligations. It does not force taxpayers to make higher and

higher interest payments on a growing national debt. It does not give the

government an excuse to keep taxes high. These are just a few examples of why,

in moral terms, debt-free fiat money causes less harm to free markets and

individual liberty than debt-based fiat money.