Translating deep thinking into common sense

Does the Fed Print Money? Or Just Create Credit?

By Keith Weiner

January 17, 2016

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

There is a populist idea of money printing. The idea is that banks can just print what they want, enriching themselves in a massive fraud. But, does it really work this way?

Let’s start with a simple case, which is clearly not money printing. We will build a series of examples by adding one element at a time, working our way up to banks, and eventually the central bank. Then we can examine this idea of printing.

Creditors today accept central bank liabilities only because they are forced to. Central banks have no incentive for prudence.

Henry Homeowner finds the perfect house, goes to a bank and gets a mortgage. He is clearly not printing (the bank isn’t printing what it lends to him either, so please bear with me until the end). This example illustrates the concept of the balance sheet. Henry did not get one penny richer merely by borrowing to buy the house. It is true that he now has a house, an asset he did not own previously. However, the house is balanced by a mortgage, a liability he didn’t have before, either.

Next is Barry Bondholder, who gets a loan to buy a bond. Now he has an asset (the bond) and a liability (the loan). Would anyone say that Barry printed money? Barry is only different from Henry, in that he bought a bond instead of a house.

Next, consider the case of Frank Flipper. He takes out a balloon mortgage to buy a house. He paints over the olive drab walls, and adds some new carpet without cat pee. He sells the house for a profit, and repays the mortgage. Then he does it again. Is Frank printing money while he flips houses? Frank differs from Henry, in that he has to sell the asset to repay his short-term funding.

Frank’s brother, Magnus, scales up Frank’s business. He sets up a process with the bank to automate borrowing and repaying. Funding the mortgage to buy a house is as simple as pressing a button. When he sells, another button repays the mortgage. He develops such high turnover, that he is always buying a new one just as he is selling an old one. The loan repayment of one replenishes his credit, just in time to get the next one. Is Magnus printing money? Magnus is different from Frank, because his good credit persuades the bank to give him discretion to initiate his own loans.

Next let’s look at Bob Banker, Barry Bondholder’s cousin. Bob sets up a credit line to grow his bond business. When he finds a good bond, he can hit a button to borrow the funds to buy it. Would you say that he’s printing money? Like Magnus, Bob can borrow what he wants.

Bob’s son, Morgan, expands the family bond business by borrowing from retail savers and corporations. Does Morgan finally cross the threshold into money printing? Morgan is different from the others. Morgan’s business is a bank, using depositor money.

Finally, let’s look at Bill Trader. His firm buys and sells Morgan Banker’s debt. He is a market maker, and his trading provides liquidity to Banker debt paper. He is so successful, that wholesalers begin to accept it in payment of their invoices, because it suits them better than the alternatives. Does Bill turn Morgan into a money printer?

These examples could all take place in a free market, but unfortunately, we don’t have one. We have central banks. A central bank is similar to Henry, in that it issues liabilities to fund the purchase of assets. Like Barry, the central bank does not deal in houses, but bonds. Like Magnus and Bob, the central bank has discretion to issue liabilities whenever it wants to buy an asset.

A central bank is quite different, but not because it can print money. Unlike the wholesalers who accepted Banker paper, creditors today accept central bank liabilities only because they are forced to. Central banks have no incentive for prudence, as Bill and Morgan did. The law gives them cover to dispense with any need for care, or even honest dealing. Demand for central bank debt paper is seemingly unlimited, at least so far.

“Money is gold, and nothing else,” said John Pierpont Morgan, in his testimony before Congress in 1912.

The central bank is not printing, but borrowing. It does not get anything for free, but merely expands its balance sheet. It has a new liability to balance its new asset. In our banking system, there is no such thing as printing. Also, despite popular misconception, the debt paper of the central bank is not money, but credit. We’ll let an expert banker give the proper definition.

“Money is gold, and nothing else,” said John Pierpont Morgan, in his testimony before Congress in 1912.

But just because the central bank is not printing, it does not mean that it’s not doing something copiously dangerous. Like other central banks, the U.S. central bank, the Federal Reserve, was ostensibly created to inject more stability in the economy.

Mainstream economists tell us that the Federal Reserve protects us from economic waves, indeed from the business cycle itself. In their view, people naturally tend to go overboard and cause wild swings in both directions. Thus, we need an economic central planner to alternatively stimulate us and then take away the punch bowl.

Prior to the global financial crisis of 2008, a popular term described the supposed benefits created by the Fed. The Great Moderation referred to the reduced volatility of the business cycle. For example, I have written before about economist Marvin Goodfriend, who asserted that the Fed does better than the gold standard.

This belief is inherent in the Fed’s very mandate from Congress. The Fed states its three statutory objectives as, “maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” These terms are Orwellian. Maximum employment means five percent of able-bodied adults can’t find work. Stable prices are actually rising relentlessly, at two percent per year. The meaning of moderate long-term interest rates must be changing, because rates have been falling precipitously for a third of a century.

The business cycle is vastly more complicated than the crop cycle. It plays out over decades. It involves every participant in the economy. It affects every price, including, and especially, the price of money.

That aside, the basic idea is that the Fed has both the power and the knowledge to somehow deliver an economic miracle. However, we know that central planning never works, even for simple things such as wheat production. Communist states have invariably failed to produce the food to keep their people alive. Stalin, Mao, and other communist dictators have deliberately starved off segments of their populations that they couldn’t feed.

The business cycle is vastly more complicated than the crop cycle. It plays out over decades. It involves every participant in the economy. It affects every price, including, and especially, the price of money. It causes changes in how people coordinate in the present and how they plan for the future. And, there are feedback loops. Changes in one variable cause changes in others, which come back to affect the first variable. The very idea of centrally planning money and credit boggles the mind.

This should not be controversial. Yet, even those who know why government food planners fail, somehow retain their faith in central planning of the economy as a whole. Marvin Goodfriend—who spoke in favor of free markets, by the way—called his faith in central banking, “optimism.”

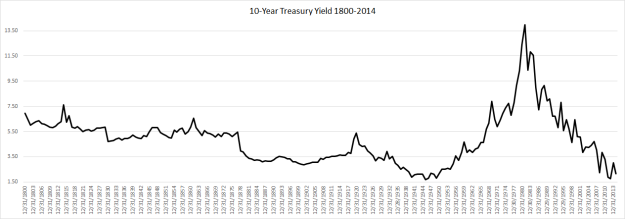

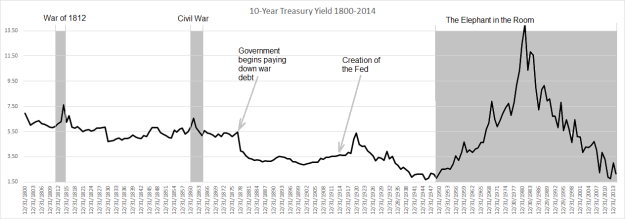

Is it true that the Fed is actually somehow providing stability, or even improving on a free market? Let’s look to the interest rate on the 10-year Treasury bond. The rate of interest is a key economic indicator.

With that giant peak on the right side of the graph, we can immediately reject all claims to Fed-imposed stability.

Now let’s label a few key dates.

(Sources: National Bureau of Economic Research 1800-2001, US Treasury 2002-2014)

The pre-Fed period is pretty stable. Two spikes occur due to wars that we know disrupted the economy—and they’re pretty small, considering the post-Fed period volatility. Interest declines to a lower level when the government was paying down its war debt. Things remain stable until the creation of the Fed.

After that, we get a rise, a protracted fall, an incredible and truly massive rise, and an endless freefall. Both rising and falling interest make it more difficult to run a business that depends on credit, such as manufacturing, banking, or insurance. The post-Fed period is a lot less stable than the pre-Fed one.

A feature of the free market and its gold standard is interest rate stability. The rate can vary between the marginal time preference and marginal productivity. This tends to be a stable and narrow range.

Fed apologists argue that the economy would be even more unstable, if we had no monetary central planner. However, the fact is that it became a lot less stable after the Fed was created.

And that’s what we should expect if we insert into the economy, an entity that can borrow with reckless abandon, unconstrained by economic law. Never mind the fact that it can’t print money.

The bulk of this essay appeared across two articles from Keith Weiner’s weekly column, called The Gold Standard, at the Swiss National Bank and Swiss Franc Blog SNBCHF.com.