Translating deep thinking into common sense

Donald Trump and the Age of the Loudmouth

By Kurt Keefner

September 28, 2016

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

A lot has changed in American media in the last few decades. Talk radio, the Internet, social media, and reality TV have altered the way in which Americans think. This new style of thinking has created a niche in which a person like Donald Trump can flourish.

We are living in an Age of the Loudmouth. This formulation may sound like a meme or one of those clever things that bloggers say. But there is a lot more to it if we are willing to dig deep.

There are a lot of negative opinions out there about Donald Trump. He is the perfect storm of American politics. He is a train wreck. A Trump presidency would be an extinction-level event.

He is a bad person.

Many explanations for Trump’s popularity have been put forward. The commonest involves the anxieties felt by middle- and working-class white people. Many such people feel that their standard of living is stagnating, that their jobs are leaving America or are being “taken” by immigrants, and that nothing is being done about the creeping menace of Radical Islam. Trump speaks to these anxieties.

Another, related explanation is that fear triggers a latent authoritarian tendency in many Americans that draws them to a demagogue like Trump.

A third is that Trump is perceived as the battering ram that will break through the self-serving establishment in Washington. This explanation explains the fact that many anti-establishment conservatives support Trump even though he has a history of espousing views that are not traditionally right wing.

A fourth account of the Trump phenomenon is more technical. It claims that the weakening of the structural processes of both parties has made it possible for an unvetted outsider like Trump to sneak into the castle and seize the princess. On this view, political reforms intended to make the parties more democratic have backfired.

These explanations of Trump’s popularity are valid, as far as they go. But there is more to explain. We are still left with a seemingly unanswerable question: Why would sane people, even desperate ones, stubbornly get behind a man who is so transparently a clown? What is going on in their minds? I hesitate to add yet another conjecture to the list of explanations of Trump’s popularity, but I would argue that the answer is that there has been a radical shift in American consciousness over the last few decades. I am not referring to the contents of consciousness, but to its operation.

Behold the Loudmouth

The shift in consciousness can be summarized in a pithy formulation: We are living in an Age of the Loudmouth. This formulation may sound like a meme or one of those clever things that bloggers say. But there is a lot more to it if we are willing to dig deep.

To begin with we need a working definition of a loudmouth. From Merriam-Webster: a loudmouth is “a loud person: a person who talks too much and who says unpleasant or stupid things.” As I use the term it encompasses being a bloviator, a ranter, a windbag, a know-it-all, a bullshitter, or a vocally opinionated person. One does not have to be literally loud to be a loudmouth in the sense I mean it, but it helps. The paradigm of loudmouths in contemporary America is Rush Limbaugh. Of course, loudmouths have always been with us. But after a partial lull in the mass media of most of the American twentieth century, they are back in force, amplified and validated by new media.

Orality deals more in concretes while literacy favors abstractions. Orality strings ideas together by simply piling one thing upon another, using words such as “and” and “now.” Literacy builds a structure using words such as “because” and “therefore.”

How has American consciousness changed in the last few generations? Let us concentrate on some fundamentals: Scholars such as Eric Havelock, Marshall McLuhan, and Walter Ong have chronicled different operational styles of consciousness. Boiling it down a bit, the basic styles are “orality” and “literacy.”

“Orality” refers to the mindset of people for whom the spoken word is dominant, as opposed to the written. This is in contrast to the “literate” mindset in which the written word dominates. Many people who are technically literate are oral in their thinking style and even their writing. Tweets would be a good example of such writing. At the same time many people who are dominantly literate not only write but even speak in a “literary” manner, the extreme here being college professors and writers such as George Will.

Following Walter Ong here, orality and literacy organize the mind in quite different ways: Orality deals more in concretes while literacy favors abstractions. Orality strings ideas together by simply piling one thing upon another, using words such as “and” and “now.” Literacy builds a structure using words such as “because” and “therefore.” Orality deals more in personalities and conflict where literacy allows a distance from the subject at hand and at least the potential for objectivity. Orality utilizes stock phrases and repetition where literacy tends to employ fewer clichés and develops in a more linear progression.

Right off the bat, it seems obvious that Donald Trump uses an oral style more than any other current or former candidates for president, especially Ted Cruz and Hillary Clinton. These two rivals have been public speakers, but with a difference. Cruz was a champion debater in college. Formal debate is highly literate in its approach. Clinton first attracted notice as a speaker at her Wellesley College graduation, which I think we can assume was not the same style as a Trump oration.

Trump’s rhetoric is based on simple, repetitive ideas, even more than most politicians’ ideas are. His speaking is peppered with oralistic side-comments such as “I guarantee you …” and “It’s going to be huge,” which would be interruptions of what would be a linear flow in literate oratory. And of course, he deals to an extraordinary degree in personalities, characterizing his opponents as “Lyin’ Ted” and “Crooked Hillary.”

If you summed up this aspect of the Trump phenomenon in a meme, and of course someone has, it would be: “Donald Trump is what would happen if the comments section became human and ran for president.”

One might object that of course Trump seems oralistic, because Trump is notorious precisely for his speaking, which one would expect to be oral in its style. But speaking, especially public speaking, does not have to be so oral. Think of Abraham Lincoln. Even on their more modest, sub-Lincoln scales, presidents such as Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama, who also have done a lot of public speaking, are not nearly as oral as Donald Trump.

In large measure this is due to the fact that most politicians work from a script (literate influence here) whereas Trump is more extemporaneous. That is what a lot of Trump’s supporters like about him: He says what’s on his mind instead of what a bunch of speechwriters, guided by their focus groups, tell him to say. Many frustrated people probably feel that the scripted message is the manipulative message, just further empty promises. Trump is oralistic on principle, as well as because of his temperament, and his followers love it.

Even When We Write, It’s Still Like Speaking

We have become more oral than the last few generations were, reverting to an almost nineteenth-century level. (For an overview of how oral nineteenth-century “literature” and “journalism” were, see Neil Gabler’s Life: the Movie.) The reversion to orality takes two forms. The first of these is what Walter Ong called “secondary orality.” This is the orality made possible by recording and broadcasting, as opposed to speaking in person. It stands in contrast to “primary orality,” which is the orality of pre-literate people.

Secondary orality depends on literate people designing and operating the electronic equipment that makes it possible to get words and songs out to millions of listeners thousands of miles away from their point of origin, but the message is still spoken or sung, not written.

Examples of pure secondary orality include talk shows, political round tables, stand-up comedy broadcasts, reality TV to the extent it is improvised, presidential debates (which have become reality TV), and any radio or TV program (such as a televised Trump rally) that is not heavily scripted. Borderline cases would include songs, speeches, comedies, and dramas that are based on written scripts, but that have a casual and naturalistic, and thus oralistic, style.

Radio and TV do not have to be heavily oralistic—shows like The Twilight Zone were quite literate—but they have a natural tendency in the direction of oralism. Even thoughtful pieces such as NPR interviews are still oral (because they are interviews) and oralistic (because of the need to be brief and easily digestible).

Trump of course had his own reality TV show and has been involved in media spectacles such as professional wrestling and beauty pageants, so one might say that he has long been a creature of secondary orality.

Loudmouths Howard Stern and Rush Limbaugh are the patron saints of secondary orality and each stands in relation to Donald Trump as John the Baptist stood in relation to Jesus of Nazareth: Trump is the realization of their Word. Take Stern’s infantile smuttiness and Limbaugh’s bloviating, add several billion dollars and an uber-New York attitude, and you get Trump the loudmouth. Note that Trump has appeared several times on Stern’s show (which in itself disqualifies him from consideration as a serious human being) and has received Limbaugh’s approval if not outright endorsement. (Limbaugh does not give formal endorsements.)

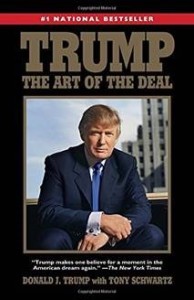

One might counter that Trump has a literate side in that he has also written a number of books, the latest of which was his extended campaign pamphlet, Crippled America. However, this pamphlet reads as if it were dictated, not written, with its stock phrases and circling back to cover points a second or even third time. According to The NY Daily News, Crippled America was ghostwritten. If that’s true the ghostwriter deliberately gave the book Trump’s oralistic style. Some of his other books have co-authors who no doubt put Trump’s style into somewhat more literate terms.

This goes back to Trump’s first book. Tony Schwartz, the ghostwriter of Trump’s breakthrough book The Art of the Deal, has said that it was difficult to work with Trump and that he believes Trump would be a bad president. “One of the chief things I’m concerned about is the limits of his attention span, which are as severe as any person I think I’ve ever met.” A shortened attention span seems to be one of the characteristics of secondary orality.

This goes back to Trump’s first book. Tony Schwartz, the ghostwriter of Trump’s breakthrough book The Art of the Deal, has said that it was difficult to work with Trump and that he believes Trump would be a bad president. “One of the chief things I’m concerned about is the limits of his attention span, which are as severe as any person I think I’ve ever met.” A shortened attention span seems to be one of the characteristics of secondary orality.

Despite his forays into the written word, Trump’s utilization of—one might almost say, identity with—secondary orality is nonpareil among recent public figures. He is a loudmouth par excellence. But what I am suggesting is that this utilization works because Americans have become more oral in their thinking. I will return to this claim later.

The second form that the reversion of an oral mindset takes could be labeled “oral literacy.” This paradoxical phrase is intended to capture the way in which so much of written language today has an oralistic style. Examples abound: social media, texting, many blogs, and, of course, the comments section. To be sure, many people use these media in a more-or-less literate style, but the bulk of them contain simple syntax, a lot of emotionalism, a focus on personalities, and the other earmarks of orality. Emojis, for example, replace the gestures and tone of voice of oral communication.

This is encouraged by the format of such writing—a tweet on Twitter must be 140 characters or less, for example—and by the necessity to hold the reader’s attention when surfing away is so easy. Nicholas Carr has documented this flitting cognitive style in his book The Shallows. When an old-fashioned reader picks up a newspaper, magazine, or a book, she is generally making a tacit commitment to seeing it through, a commitment that requires patience and the belief that the author might actually have something worthwhile to say. But today, such commitment is relatively rare. As Neil Gabler points out in Life: the Movie, what modern Americans want is to be entertained.

The Crisis of the American Mind

I would liken the American desire to be entertained to the crisis of the American diet. We’ve always had a taste for carbohydrates, grease, sugar, and salt, but when they became so easily available and other things became downplayed, they became an addiction. They light up the brain, which was programmed by evolution to want these things when they were available, which was occasionally, not every day.

The same holds for entertainment. People have always craved entertainment, but compared to several centuries ago, it is now widely available and cheap, and far more people have far more leisure time to spend on it. And so a natural desire becomes an addiction. This is the danger of things being too easily available: A frightening number of people do not have the ability to delay gratification long enough to eat right or save money, let alone read a book—or even a long sentence.

This might all sound like another tired attack on television and its corrupting effects, but it is not. I am not claiming that secondary orality and oral literacy are a new phenomenon. What I am claiming is that the rise of modern media has validated them as cognitive styles and provided role models for groups of Americans who used to aspire to better. Once upon a time the lower middle class read The Reader’s Digest and bought books on proper spelling of confusing words. Now they watch Bridezilla and read People magazine. I am exaggerating of course, but not by much.

Cable television and talk radio make secondary orality widely and easily available and the Internet does the same for oral literacy. Inundated in this new-old style, the mind becomes too impatient for critical thought to be entertained, too high on sensationalism and sensationalistic opinions, too much in love with the sound of its own voice. Thus, we get the rise of the loudmouth.

Fans of Rush Limbaugh often apply that unflattering label [ditto-head] to themselves. It refers to their lockstep agreement with Limbaugh. Remember that Limbaugh is a man who refers to feminists as “feminazis,” an unmistakable instance of loudmouth oralism. And Limbaugh has a weekly audience of over 13 million listeners.

The state of TV news and opinion tends to confirm my hypothesis about the changing American mindset. Compare the rise of the recent round table discussions at Fox News and MSNBC to the thoughtful discussions of older shows such as This Week and The News Hour. Furthermore, it is indicative of our time that many people go to comedians such as Stephen Colbert and Bill Maher for their political information and opinions. Saturday Night Live has long had its Weekend Update feature, but it had no pretentions to being serious. Now some people watch The Daily Show with near-reverence. The humorous medium truly has become the message. The superficialization of America is nearly complete, and you can hear Donald Trump laughing in the background.

There has been another noteworthy change, largely due to the development of the Internet, and that is the decline of the gatekeepers. Once upon a time the things we read and saw were filtered through publishers and editors, most of whom had some standards. Cheap attacks were removed from most twentieth-century newspapers. Penny dreadfuls were replaced by better general fiction. TV had to be appropriate for the children in the house. Of course, I am painting a rosy picture of the past, but as a general picture, allowing for many exceptions, it seems to be true.

Cable television, talk radio, and the Internet changed all of this. The genie was let out of the bottle. In some ways this was a good thing. For many years, the liberal side of the political spectrum controlled the news departments of the TV networks and the elite newspapers and magazines. Opening up the forum was in some ways healthy for democracy. But a lot of bad things got out of the bottle too, including loudmouths from both ends of the political spectrum.

Being a Loudmouth is OK

Many people now believe that carrying on like a loudmouth is an acceptable form of discourse and that it is fun. More fundamentally, many people not only act like loudmouths, but think like loudmouths. I don’t have any studies to back this up, because as far as I know, no one has studied this. But observable trends seem to support my generalization.

For example, look at the rise of the “ditto-head.” Fans of Rush Limbaugh often apply that unflattering label to themselves. It refers to their lockstep agreement with Limbaugh. Remember that Limbaugh is a man who refers to feminists as “feminazis,” an unmistakable instance of loudmouth oralism. And Limbaugh has a weekly audience of over 13 million listeners.

For other examples, just look at Twitter. Donald Trump’s notorious jabs at “Low Energy Jeb,” “Little Marco,” “Lyin’ Ted,” and “Crooked Hillary,” are nothing new at all. Twitter regularly descends to shouting matches and even death threats, including threats of rape and murder over Star Wars. (!) Or look at the round table political discussions on most networks: five people shooting their mouths off, sharing mere “opinions.” These opinions are often little more than rants with a veneer of civility.

In addition, consider the wild theories that have possessed our fellow Americans: the vaccinations-cause-autism theory and the birther theory come to mind. Crazy theories tend to be associated with the political right in the U.S., but liberals are not above conspiracy-thinking. A poll taken by Politico showed that over half of all Democrats thought it was somewhat likely that the government (i.e. the Bush Administration) knew about 9/11 in advance and did nothing because they wanted an excuse to make war in the Middle East.

We’re not quite back to the age of the blood libel against the Jews, but we have been heading in that direction. Examples could be multiplied indefinitely. But it’s clear that loudmouth speech and thought, i.e. the worst kinds of oralistic thinking, have been on the rise. Trump’s and his supporters’ ranting, oralistic style of thinking precludes long-term, critical thinking. This is also, in its foundation, nothing new. It was only a matter of time until the rotten timbers gave way.

The President We Deserve

So where is all this heading? Well, first of all, I have been trying to make clear that the problem isn’t Trump per se—it’s us and our way of thinking. Trump might not win this election, although it chills me to have to say “might.” But even if Mrs. Clinton—or as a long shot, Gary Johnson—is elected, there will surely be another Trump in a few years. Our style of thinking shows no signs of getting better.

I am not going to pretend that I have solutions for the problems I have tried to identify. Trump’s supporters are probably too far gone to listen to reason. One thing is for certain: We are not going to give up TV and the Internet. The genie is not going back into the bottle.

What is necessary and possibly helpful would be to start a conversation among concerned people throughout the ideological spectrum about how to stop the slide down the slippery slope to loudmouth oralism and maybe even crawl back up to a safe level. Perhaps we could arrange a summit of reason, with such people as Jonathan Haidt, Nicholas Carr, Jaron Lanier, George Will, Neil Gabler, Gerald Graff, Camille Paglia, and Michael Strong. (I offer these names purely as an illustration of one possible set.) Computer and web innovators such as Tim Cook and Mark Zuckerberg should also be invited, so they might help design an architecture that will encourage a literate mindset.

What I am suggesting is that massive reform may be necessary. Reform of TV programming, the Internet, and American education seems impossible. But I don’t think it is. Look at the way in which America has changed itself with regard to race and gender equality over the last fifty years. If that was possible, than almost anything is possible. Furthermore, we have a powerful incentive for reform: We need to stop future Trumps, because even if this one loses, others will rise to take his place. If we don’t take action against the loudmouth-type in American society, eventually we will get a president who matches the way we think.