Translating deep thinking into common sense

Fiction’s Most Unusual Romantic Triangle

By Marco den Ouden

December 8, 2023

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

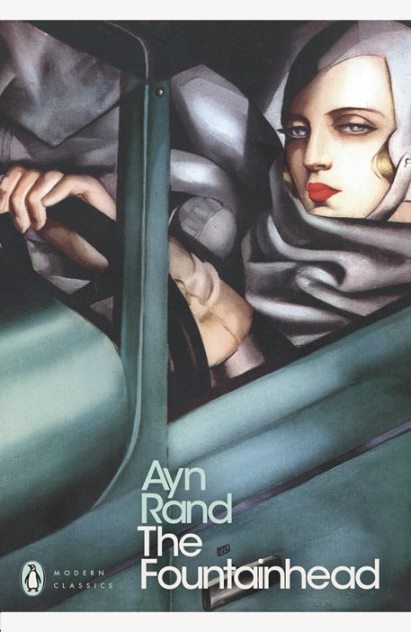

Ayn Rand was fond of love triangles. In her fiction, love triangles play a role in all three of her major novels. We the Living features Kira, Leo and Andrei in such a relationship. The Fountainhead features Dominique, Roark and Wynand in such a relationship. And Atlas Shrugged features Dagny involved with Francisco, Rearden, and Galt, more a quadrangle than a triangle.

Love triangles play a role in all three of her major novels.

What is a romantic triangle? According to Wikipedia “A love triangle or eternal triangle is a scenario or circumstance, usually depicted as a rivalry, in which two people are pursuing or involved in a romantic relationship with one person, or in which one person in a romantic relationship with someone is simultaneously pursuing or involved in a romantic relationship with someone else. A love triangle typically is not conceived of as a situation in which one person loves a second person, who loves a third person, who loves the first person, or variations thereof.” In other words, a love triangle is not the same as a ménage à trois.

Wikipedia continues: “The term ‘love triangle’ generally connotes an arrangement unsuitable to one or more of the people involved. One person typically ends up feeling betrayed at some point … A similar arrangement that is agreed upon by all parties is sometimes called a triad, which is a type of polyamory even though polyamory usually implies sexual relations.”

In any event, the relationship between Dominique, Wynand and Roark is a most unusual one.

In any event, the relationship between Dominique, Wynand and Roark is a most unusual one. Usually a love triangle involves a person of one sex loved by two persons of the opposite sex. In The Fountainhead, this notion is turned on its head. It is Roark who is in love with both Dominique and Wynand. But neither Roark nor Wynand are bisexual, so theirs is a profound, platonic love. But it is a genuine love all the same.

And the relationships between the protagonists, while love relationships, also involve deep conflicts. Roark is the only “whole” person in the relationships though both Dominique and Wynand have the potential for such “wholeness.”

To get at the complexity of this triangle we need to start with the famous “rape” scene. Rand was quite clear that this supposed “rape” was not one. In a 1965 reply to a fan who expressed concern about the scene, she wrote, “It was not an actual rape, but a symbolic action which Dominique all but invited. This was the action she wanted and Roark knew it.” (Andrew Bernstein in Essays on Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, ed. Robert Mayhew, 201)

Shoshana Milgram writes that, in her notes, Rand included scenes left out of the final cut that more explicitly explained their relationship. Rand’s favorite stylistic method was to show ideas through actions rather than description. In the first draft, she wrote of Roark’s reaction on first seeing Dominique at the quarry. He saw a challenge, “a woman with an invisible stamp, his own stamp, upon a white face that presented to him the final, the complete reality of what he had sought, of what he had found but a hint of in others.” (in Essays, 18)

And part of this view is sometimes manifested in “invited” physical domination. Milgram quotes more of Roark’s mindset that enhances this idea.

He and Dominique share a similar view of sexuality, the same view as Rand herself, of femininity being manifested in looking up to a man, in “hero worship.” And part of this view is sometimes manifested in “invited” physical domination. Milgram quotes more of Roark’s mindset that enhances this idea. “That face was freedom—a freedom proud enough to warrant enchainment[?]; it was strength—sure enough of itself to be fought; it was will—great enough for the honor of being broken … He knew that he wanted to break this woman.”

In the novel, this is dropped entirely. Rand, in fact, shifts the point of view of the relationship from Roark to Dominique. In the draft, Dominique’s thoughts were expressed when Roark seemingly violates her as: “She fought because she could not bear the pleasure. She fought because she hated herself for that pleasure. She fought because she wanted him too much.”

In the book, however, those inner thoughts are dropped and replaced. Dominique’s thoughts as Roark kisses her are “She did not know whether the jolt of terror shook her first and she thrust her elbows at his throat, twisting her body to escape, or whether she lay still in his arms, in the first instant, in the shock of feeling his skin against hers, the thing she had thought about, had expected, had never known to be like this, could not have known, because this was not part of living, but a thing one could not bear for longer than a second.” (The Fountainhead, 219) This idea of not remembering the event as an expression of extreme desire comes up again later as we shall see.

Bernstein elaborates that Dominique was the aggressor in the encounter from beginning to end, quoting from the finished novel to make his point. On her first seeing Roark at the quarry, “She thinks that his ‘is the most beautiful face she would ever see, because it was the abstraction of strength made visible.’” She gives him the eye, admiring his body. Contemplating “his hands that break granite, (she) feels ‘weak with pleasure’ at the thought of being broken.” (in Essays, 202)

She deliberately smashes the marble in front of her fireplace to have an excuse to summon Roark to her home. “Dominique waits for the marble with the ‘feverish intensity of a sudden mania.’” She reacts with shock when an old portly Italian man comes to set the stone. A few days later, she overcomes her resistance and goes to the quarry again. She is on horseback and spots Roark on the road walking home. She is carrying a branch she ripped off a tree. She demands to know why he didn’t come to set the stone himself. When he replies, “I didn’t think it would make any difference to you who came. Or did it, Miss Francon?” she slashes his face with the branch.

“The evidence is conclusive,” Bernstein writes. “Dominique feels an overwhelming attraction to Roark. She is the aggressor throughout the scene—flaunting her name and her beauty, scratching the marble, pursuing Roark after work, striking him with the branch. The sexual tension Dominique feels explodes in her act of violence. Through this action, she makes explicit to Roark what had been implicit—that she wants him in the strongest way, and that the frustration of not having him is unendurable.”

Her resistance is based on her tragic flaw, described by Rand herself thus: “She was devoted to values, was an individualist, had a clear view of what she considered ideal, only she didn’t think the ideal was possible. Her error is the malevolent universe premise: the belief that the good has no chance on earth, that it is doomed to lose and that evil is metaphysically powerful.” (Ayn Rand Answers:The Best of her Q&A, editor Robert Mayhew, 191, quoted by Bernstein in Essays, 203)

This malevolent universe premise has her struggle to destroy Roark’s career as a pre-emptive strike against a world that does not deserve him, and in a misguided attempt to save Roark from what she sees as his ultimate defeat. Perversely, this puts her into a sort of partnership with Toohey to destroy Roark.

Jeff Britting elaborates in an essay on adapting The Fountainhead to film. He quotes from notes by Rand. “The more she desires him, the more certain she is that he will be destroyed. She is so hurt herself that she is driven to hurt him but her cruelty to him is only an extreme expression of her love.” (in Essays, 104)

Roark realizes her despair, but he also knows he wants her “voluntary acceptance” of the benevolent universe premise he holds. “He will not force his ideas on anyone,” especially not Dominique.

Dominique’s and Rand’s views on sexuality, while not my cup of tea, are, in fact, very common.

Some feminists have criticized the rape scene believing it to be an actual rape. But as argued above, this is not the case. Dominique’s and Rand’s views on sexuality, while not my cup of tea, are, in fact, very common. There is a whole dominant/submissive sexual sub-culture. A January 2023 article in Psychology Today reports on a 2015 survey by researchers at Indiana University that “showed that elements of BDSM were fairly popular, such as spanking (30 percent), Dominant/submissive (D/s) role-playing (22 percent), restraint (20 percent), and flogging (13 percent).” (Michael Castleman, “BDSM Is Increasingly Mainstream, and It Boosts Intimacy”, Psychology Today, January 16, 2023)

The 2011 potboiler Fifty Shades of Grey series sold over 150 million copies over six years. The books, which glorified bondage and discipline, were especially popular with women. So maybe the portrayal of Dominique as a woman who goes riding through the woods not knowing what to expect, “only its quality—the sensation of a defiling pleasure,” (The Fountainhead, 206) is not far-fetched but decades ahead of its time. When she looks at Roark for the first time, she is spellbound. When he looked at her, “she knew that she could not move until he permitted her to.” (207) She feels “a convulsion of anger, of protest, of resistance—and of pleasure.” His glance is “an act of ownership,” and “she was wondering what he would look like naked.” Their communication is silent but it communicates the language of dominance and submission.

Dominique marries Keating to hurt Roark, but she does not love Keating and feels contempt for him. She does not respond to him sexually, just lying there unresponsive when he takes her. She doesn’t resist. But she doesn’t respond. It’s like she’s not really there.

When he speaks to her, Keating thinks “It makes no difference to her at all whether I speak or not; as if I didn’t exist and never had existed … the thing more inconceivable than one’s death—never to have been born … He felt a sudden, desperate desire which he could identify—a desire to be real to her.” (The Fountainhead, 438)

But her reaction to Wynand is quite different. On their yacht trip they recognize their fundamental compatibility and talk about love and life. They talk about their love of skyscrapers. “I would give the greatest sunset in the world for one sight of New York’s skyline,” Wynand tells her. (463)

“Gail,” she responds, “I don’t know whether I’m listening to you or to myself.” (464) The visibility missing from her marriage to Keating is starting to develop in her relationship to Wynand.

The trip was ostensibly to secure a commission for Peter Keating. It was expected she would sleep with Wynand but he has resisted inviting her to his bed. “When are we going below?” she asks. “We’re not going below,” he replies.

He pauses, then asks her to marry him. He understands fully her motives. “You’ve chosen me as the symbol of your contempt for me. You don’t love me. You wish to grant me nothing. I’m only your tool of your self-destruction. I know all that, I accept it and I want you to marry me … Incidentally—since it is of no concern to you—I love you.” (465)

She agrees to marry him because she sees the idea of being Mrs. Wynand-Papers as the ultimate degradation, but she can’t help but respond to Wynand because he actually shares much of her view of life. He says he won’t consummate their relationship until after the wedding, but he does kiss her. “It was the completion of his words, the finished statement, a statement of such intensity that she tried to stiffen her body, not to respond, and felt her body responding, forced to forget everything but the physical fact of the man who held her.” (466)

On their wedding night she tries to show a “rigid indifference” (502) but “she felt the answer in her body, an answer of hunger, of acceptance, of pleasure. She thought that it was not a matter of desire, not even a matter of the sexual act, but only that man was the life force and woman could respond to nothing else; that this man had the will of life, the prime power, and this act was only its simplest statement, and she was responding not to the act nor to the man, but to that force within him.”

Now read this description of the first meeting between Wynand and Roark and think about what it reminds you of: “Wynand was not certain that he missed a moment, that he did not rise at once as courtesy demanded, but remained seated, looking at the man who entered; perhaps he had risen immediately and it only seemed to him that a long time preceded his movement. Roark was not certain that he stopped when he entered the office, that he did not walk forward, but stood looking at the man behind the desk; perhaps there had been no break in his steps and it only seemed to him that he had stopped. But there had been a moment when both forgot the terms of immediate reality, when Wynand forgot his purpose in summoning this man, when Roark forgot that this man was Dominique’s husband, when no door, desk or stretch of carpet existed, only the total awareness, for each, of the man before him, only two thoughts meeting in the middle of the room—’This is Gail Wynand’—’This is Howard Roark.’” (540)

This is a perfect description of love at first sight. And it echoes Dominique’s thoughts when Roark first kisses her. A moment when there is a loss of awareness “of immediate reality.”

Roark had been summoned by Wynand because he wanted to give him the commission to build a private home for him and Dominique at a country estate in Connecticut. Their ensuing conversation cements their relationship. Like Anne of Green Gables and Diana Barry, they are kindred spirits.

But there is also conflict. Wynand says of Dominique, not knowing of the relationship between her and Roark, “I can’t stand to see her walking down the streets of the city. I can’t share her, not even with shops, theaters, taxicabs or sidewalks. I must take her away. I must put her out of reach—where nothing can touch her, not in any sense. This home is to be my fortress. My architect is to be my guard.” (543)

He goes on to tell Roark to think of the commission “as you would think of a temple. A temple to Dominique Wynand.” (544)

After the house is built and Dominique and Wynand move in, Dominique “felt at one with the house.” (611) A telling paragraph hints at more than a triangle, but a polyamorous triad, even with Roark not there.

“She accepted the nights when she lay in Wynand’s arms and opened her eyes to see the shape of the bedroom Roark had designed, and she set her teeth against a racking pleasure that was part answer, part mockery of the unsatisfied hunger in her body, and surrendered to it, not knowing what man gave her this, which one of them, or both.”

Through Roark, both Wynand and Dominique learn to overcome their tragic flaws, Wynand’s desire to rule and Dominique’s malevolent universe premise. Wynand, sadly, later surrenders to the mob to save the Banner. But there is a hint of his ultimate redemption as he closes the Banner rather than acquiesce to Toohey.

An unusual but devastatingly powerful romantic triangle.