Translating deep thinking into common sense

How India Can Displace China as Asia’s Economic Juggernaut

By Vinay Kolhatkar

May 3, 2020

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Never in history has global sentiment against China been this rough. The other two Asian economic giants, Japan, and South Korea, are now openly canvassing a shift of their manufacturing out of China. Meanwhile, Business Insider reports that a thousand firms are mulling the prospect of specifically relocating manufacturing to India, 300 of those are actively pursuing production plans.

In that context, note the title. It’s not how India can follow in China’s footsteps. The steps to displacement by a different, but moral, route will be the ones illuminated.

This is a two-part essay.

Part I illustrates a grand heist.

Part II will lay the case for India to become an economic juggernaut.

Is China an Economic Juggernaut?

Professor Per Bylund doesn’t think so. He calls the Chinese economic miracle a sham:

The Chinese state’s grand projects are intended to boost GDP statistics. The country has an endless slate of infrastructure projects, including high-speed railways, bridges, and grand architecture.

It might look like a prosperous economy growing at warp speed, but these projects are not representative of genuine growth.

It is possible to game the gross domestic product (GDP) statistic. GDP measures activity, regardless of the economic value it produces. Imagine that America invests a trillion dollars into a high-speed rail project, a one-time Barack Obama fancy. And that private Japanese firms, in aggregate, also invest a trillion in robotics.

Suppose further that the American project ends up with ghost trains running under 10% of capacity. Leave aside servicing capital, the great cross-country railway is unable to generate revenues to meet even operational costs.

There’s nothing like a white elephant that becomes a monument to government extravagance.

There’s nothing like a white elephant that becomes a monument to government extravagance. Ironically, GDP is going up by a trillion during the very years a trillion dollars of capital is being wasted.

For contrast, let’s hypothesize that the Japanese private firms’ investment pays off so well that the net cash flow realized is three times the investment—eventually the positive contribution to GDP is three trillion.

The “white elephant”-GDP rise actually sets a country ten steps back for one false step forward. However, a “bad investment” reversal can take a decade or more to become apparent.

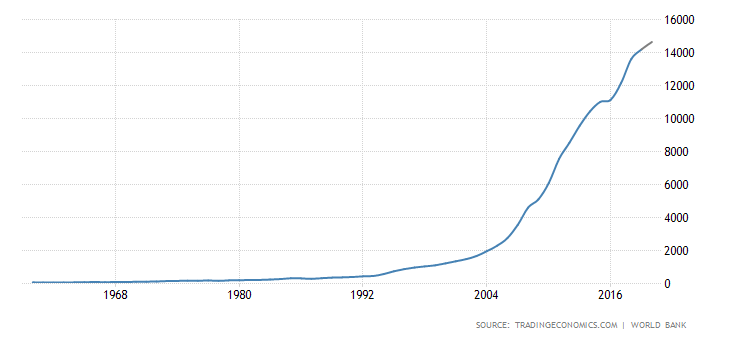

Nevertheless, the China story stands out—check out the World Bank charts (GDP in US$ billions) below—a sham will not last forty years.

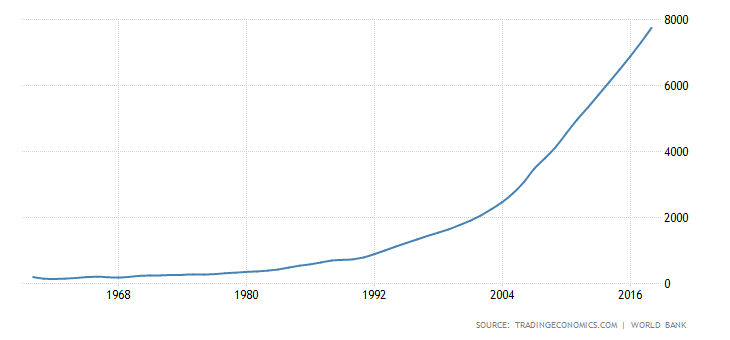

The impact of population on this exponential economic growth is significant. But the curve of “per-capita GDP” still slopes upward. Compellingly so:

That much cannot be “GDP gaming.” China outdid famine, became an exporter of capital and goods, and created a burgeoning middle class.

So now we need to answer a deeply philosophical challenge:

How Did Communist China Become an Economic Juggernaut?

It wasn’t supposed to happen. Free-market economists from Von Mises and Friedman to Rothbard and Hayek have theorized that it’s impossible.

No country has ever been free of government interference in the economy. Capitalism, in its pure form, has yet to be born. But all the evidence on display has announced that relativities matter; that higher degrees of freedom lead to more economic growth, that distribution of economic freedom on the globe is what’s truly unfair.

And there’s the Chinese Communist Party. Autocratic as hell.

And there’s the Chinese Communist Party. Autocratic as hell.

In Germany, the West drove the East to fracture the Berlin Wall. Soon after, the Soviet empire collapsed. Today, South Korea defeats its northern neighbor by many economic miles and then some, and Venezuela is no match for Chile. In every empirical observation, freedom wins. And it wins on each peg of the spectrum from fascist tyranny to a utopian fully-free economy.

Yet China stands resolutely defiant, like its centuries-old Great Wall—bucking these trends, demanding an explanation. Investopedia cites five reasons why China became the factory of the world—low labor, low taxes, lower compliance, end-to-end supply chains, and currency manipulation. But we still need to furnish an account—of how a dragon that slays individual rights can do that well.

The Key Driver of Economic Growth Is Innovation

We must revert now, briefly, to the confines of our minds. Another thought experiment! A philosopher’s delight.

Peter and Andrew Schiff take us through a parable in How an Economy Grows and Why It Crashes. I have altered it slightly for our purposes.

Let’s say two men, A and B, are shipwrecked on an island for several months without food. But potable water is available. In the shallow waters around the island, there are some fish that are not slippery enough; they can be caught by bare hands, but only after hours of trying. A and B barely get through a whole day of trying before they manage to catch just enough for one day’s sustenance. This two-man island economy is going nowhere.

Until B has an idea for a fish net. For a day he goes hungry (savings) to create a fish net (capital). The next day, he has caught plenty in an hour (productivity zooms up) for both of them. Now both men have time to think. Then A gets the idea of using wood from the barks of trees to construct a raft and oars. A and B can now fish in deeper waters.

Economic development always starts with ideas. The economic arrow is unidirectional.

Economic development always starts with ideas. The economic arrow is unidirectional—from ideas to unified concepts to experimentation to capital to manufacturing to distribution to consumption. “Aggregate supply creates its own demand” is the finest principle of economics.

Nature allows itself to be comprehended by science. But it takes considerable effort to do so. Even more mental effort is required to apply “scientific discoveries” to master nature with technology—tools, equipment, heavy machinery, and machines that run themselves (robotics).

Some ideas work, some don’t. It’s crucial to reward smart thinking (intellectual property). And risk-taking (entrepreneurship). And saving, so that it can generate investment of a sort that pays off with higher productivity. To sustain that growth, ideas need to be embedded physically, in machines and software and chemical compositions and designs (capital).

The first driver of economic growth is not capital, or savings, or investment, or entrepreneurship. It’s intellectual property (IP). You can find an exposition of this foundational concept in two books by Dale Halling: The Source of Economic Growth, and Intellectual Capitalism.

Think of what one would want saved to rebuild civilization if four-fifths of the human species was wiped out by a meteor. It would be “accumulated knowledge”—designs, algorithms, software, scientific breakthroughs, formulae, laws.

The kind of gigantic compilation that was hard to save when Alexandria’s famed library was burning—once by design, once by accident. The kind that’s now much easier to store.

Which also makes it much easier to hack into.

In the fictional film Agora (2009) set in the late 4th century, there’s a memorable scene where Alexandria is invaded. As the barbarians are about to breach the gates, philosopher-astronomer Hypatia counsels her students to rush to the legendary library, not to preserve the busts and the artefacts, but to run away with the knowledge stored in the scrolls. You can see the fascinating scene here, from minute 3.40 onwards.

Now imagine two large pharmaceutical companies, F and G. F invests half its profits in R&D. Much research goes awry, many developments are stalled by regulators. Some that succeed must pay for those that don’t.

G waits until the product hits the market and reverse engineers the composition. G has its plants in a low-labor-cost country. G is thus able to undercut F by saving on R&D as well as wages. As long as there are enough foolish Fs around who keep blazing the innovation road, G can ride on their efforts to become an international megacorporation. Many Fs may even tolerate a 20% loss of intellectual property to theft. G becomes an economic “miracle.”

Now let’s revisit the real world—see if we can locate the Fs and the Gs.

The China Story

Zhang Weiying, a professor of economics, has an Austrian-school take on China:

The fast economic development of China has resulted from the gradual introduction of markets and replacing … position-based rights with property-based rights.

Professor Weiying argues that talented people choose occupations that exhibit increasing returns to ability. And China’s reforms facilitated increasing levels of entrepreneurship.

But this cannot explain an economic “miracle.” How is it that people shying away from, or leaving, government jobs, were so transcendentally superb at business?

After all its reforms, China is still only ranked at number 103 in the Heritage Foundation’s 2020 Index of Economic Freedom (IEF). Why didn’t any of the first 100 countries secure near double-digit growth for several decades?

We have a clue—here’s what that same IEF report says of China under “Rule of Law”:

Theft of foreign-owned intellectual property is widespread. Government agencies and the Chinese Communist Party heavily influence the judicial system.

Almost one-third of CFOs on the CNBC Global CFO Council say Chinese firms have stolen from them at some point during the past decade. In this 2019 CNBC survey, 20% of them said that China had stolen their IP within the previous year—we found the Fs!

What happens to the IP that’s stolen? Let’s read the remarks of William Schneider Jr., former chair of the Defense Science Board:

It is first sent to one of China’s two dozen advanced science universities. They in turn apply for Chinese patents on the technology. After they are acquired, the government distributes the patents to various companies. One of the most notable recipients is telecommunications giant Huawei Industries. Huawei has acquired 56,000 5G and AI-related Chinese patents despite spending a pittance on R&D.

In Schneider’s words, “China has institutionalized a system that combines legal and illegal means of technology acquisition from abroad.”

The Chinese Communist Party chose to deceive the semi-free world. Why? Because it has a terrifying Marxist-Leninist agenda of domination, of reframing the world in its image. No, this is not a conspiracy theory—there are now numerous testaments of this grand plan.

See “Communist China Expects to Bury Us by 2049.” See also: The Hundred-Year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower by Michael Pillsbury, the White House China advisor, and Stealth War: How China Took over While America’s Elite Slept by Robert Spalding, a former Air Force general.

Even President Nixon changed his mind about China. In 1978, he said “We will one day be confronted with the most formidable enemy that has ever existed in the history of the world.”

State-sponsored hacking is the only means capable of a heist this grand.

But none of the peculiarly targeted “excellence” (including the amassing of stealth weaponry that specifically targets U.S. military strengths) would have been remotely easy.

State-sponsored hacking is the only means capable of a heist this grand.

And that is the China story—some GDP gaming, some lower-level economic freedom, but cronyism at the highest level—winning this big only by ubiquitous theft.

The Dark Depth of China’s Domination

Here’s one illustration of the “grand plan” in practice—the cornering of the manufacture of crucial ingredients.

In 2019, Rosemary Gibson, author, China Rx: Exposing the Risks of America’s Dependence on China for Medicine, testified before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission:

National health security and national security are threatened by U.S. dependence on China for thousands of ingredients and raw materials to make our medicines. China’s aim is to become the pharmacy to the world, and it is on track to achieve it. China’s dominance is global. European countries depend on China for medicines.

Among Gibson’s other sobering statements were:

- The U.S. has lost virtually all of its industrial base to make generic antibiotics.

- If China shut the door on exports of medicines and their key ingredients and raw materials, U.S. hospitals and military hospitals and clinics would cease to function within months, if not days.

- Our self-sufficiency in manufacturing products essential for life has collapsed.

Japan and Germany have also complained bitterly of IP theft by China. German tech giant Siemens introduced the high-speed train to China only to find that subsequent extensions of the system were done by local companies that had “learnt” the technology quickly.

It’s no surprise that displacing China as the factory of the world was already an increasing security issue before the world awoke to a secrecy that made a pandemic far worse. It took a no-nonsense American president to reverse decades of denial. A candid Trump said to ABC in 2015: “China is an economic enemy, because they have taken advantage of us like nobody in history.”

Newt Gingrich, a former professor of history, House Speaker, and a presidential candidate, dedicates a whole chapter to IP in his book Trump vs. China: Facing America’s Greatest Threat. He infers: “Engaging in IP theft is one of the key components of China’s strategy to control future industries.”

India

That the immoral have gotten away with a colossal heist does not change the only ethical model of economic growth—bandits are not productive giants.

Born of an independence from Britain that labored her with a deep distrust of foreigners, India was taken into a Soviet-style central-planning economic model that crushed its economy and mired it with corruption via a “Licensing Raj.”

It’s a democracy with a mostly-postmodernist press that favors the neo-Marxist narratives over truth. Rule of law is anything but expeditious. But it is a common law system influenced by England, with English as the language of business and university education, a population set to overtake China’s by 2030, and a growing realization that the dark cloud of the pandemic comes with a silver lining.

India would need to think in terms of decades. The way the world is mismanaging the pandemic, it could well bring forth a Great Depression for several years.

It won’t be easy for India to follow the correct path. That is in Part II.