Translating deep thinking into common sense

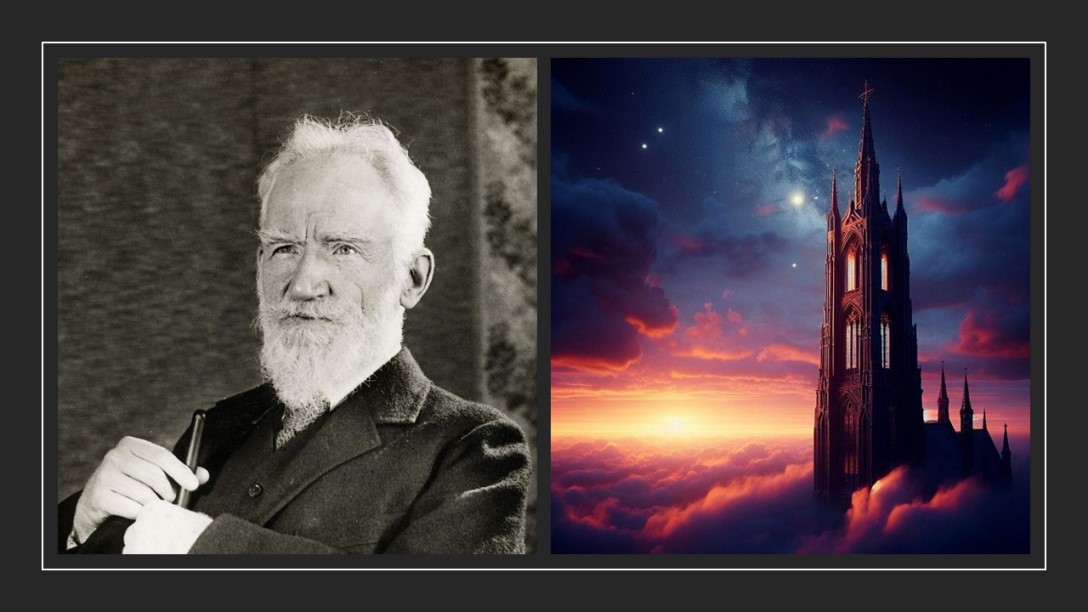

How Shaw’s “Fabian Gradualist” Socialism Became Admiration for Stalin and Hitler

By Walter Donway

August 19, 2024

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

It is no pleasure to recount the long intellectual journey of George Bernard Shaw (he lived to 94) from enthusiastic leadership of the London Fabian Society beginning in the 1880s, advocating “guaranteed” constitutional “gradualism” to achieve Marxian socialism—to mind-boggling praise and then exoneration of Benito Mussolini, Joseph Stalin, and Adolf Hitler, comments rarely retracted or modified.

Shaw became the first to win both a Nobel Prize and an Oscar.

It is not a pleasure, because Bernard Shaw (as he shortened his full name) seemed never to have had a lazy day in his life. He worked at whatever seemed necessary as a very young man, self-educating himself with fierce energy, and battering away at the gates of literary success with failed novel after novel, then failed play after play, supporting himself whatever way he could, until success slowly, then rapidly, and then like an avalanche, arrived.

He made a good living relatively early, but only worked harder, as the great plays came forth, and in 1925 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He accepted the prize but rejected the prize money: he said a playwright should be paid by his audience. Endearing. And then, for the film version of Pygmalion, with which he refused to be involved, he won an Academy Award (virulently anti-American, he described it as “an insult coming from such a source”) and became the first to win both a Nobel Prize and an Oscar.

The hoary myth that advocates of socialism are lazy, attracted out of envy for economic success, did not apply to Shaw.

No, the hoary myth that advocates of socialism are lazy, attracted out of envy for economic success, did not apply to Shaw. Instead, his failings are exclusively what Thomas Sowell characterizes as the occupational hazards of the “intellectual.” Intellectuals and Society (New York: Basic Books, 2012).

“The list of top-ranked intellectuals who made utterly irresponsible statements, and who advocated hopelessly unrealistic and recklessly dangerous things, could be extended almost indefinitely …. The fatal misstep of such intellectuals is assuming that superior ability within a particular realm can be generalized as superior wisdom or morality overall.”

Shaw may be close to the ultimate paradigm of the shortcomings of the first sentence: “advocated hopelessly unrealistic and recklessly dangerous things …” But perhaps not the second sentence. Yes, as a world-famous playwright, like today’s superstars, he used his celebrity status to “cover” for Mussolini, Stalin, and Hitler—and to chide Americans about their silly bias against “dictators”—the only ones who really accomplished something.

From Fabian Gradualism to “Dictatorship Works …”

Shaw was born in Dublin in 1856 into a family of the English Protestant Ascendancy that he characterized as living in shabby genteel poverty, but with books and music aplenty and the ability to send him to four schools, all of which he “hated” as prisons.

In 1876, he joined his mother and other family members in London, giving up Ireland for good, and began an endless series of jobs, always being rapidly promoted—and writing novel after novel, rejected by publishers. And then, the same with his plays, which certainly had no moment of “breakthrough,” but instead won success, followed by failures, and then more success.

Shaw wrote more than 60 plays, including that roster of plays, now classics, that cause critics to refer to him as “second only to Shakespeare”: Man and Superman (1902), Pygmalion (1913), Saint Joan (1926).

His involvement with political ideology long predated his success.

The struggle and the effort did not cease for more than 50 years, into Shaw’s 90s. But his involvement with political ideology long predated his success, his celebrity. He read such works as Henry George’s Progress and Poverty and was vegetarian, anti-vaccination (“witchcraft”), and pro-eugenics. In 1884, he joined the Fabian Society and became lifelong friends with Sidney Webb. He wrote the Society’s first pamphlet, its manifesto (“Fabian Tract No. 2”). He went on to provide funds for the Society’s first periodical. He attended meetings of the British Economic Association, studied Das Capital, and for a time rejected the revolutionary approach to communism advocated by Marx, instead advancing Fabian socialist “gradualism.”

As the years passed and Shaw became wealthy and celebrated, the electoral politics of socialist gradualism made no progress. On the other hand, Shaw witnessed the imposition of socialism by Leninist cadres and, later, by Hitler’s election followed by assertion of power by dictate. During the 1920s, Shaw became fascinated with dictatorial methods. It seemed to him the only thing that accomplished anything.

In 1922, he remarked that Mussolini, who had come to power in Italy amid “indiscipline and muddle and Parliamentary deadlock,” was “the right kind of tyrant.” His famous Fabian Society colleague, Beatrice Webb, characterized Shaw as “obsessed” with Mussolini. Here, at last, was the path to socialism—that obvious ideal so long delayed.

Today, all leftwing theories postulate that socialism/communism and fascism (national socialism) are opposite and utterly antagonistic political systems. Shaw, witnessing emergence of both in real time, easily recognized both as variants on socialism. The chief difference: one was putatively “internationalist” (communism) and one virulently nationalist (fascism). One advocated public ownership of property (communism) and one government control of property (fascism). In practice, of course, government alone controlled property, including “publicly owned” property, under both systems.

Stalin and Hitler Make Socialism “Work”

In the early 1920s, Shaw conceived an enthusiasm for the Soviet Union, hailing Vladimir Lenin as “the only really interesting stateman in Europe.” Still, Shaw resisted several chances to visit the Russian “workers’ paradise” until, in 1931, he traveled there with a group led by Nancy Astor. It was a typically carefully managed tour of what the Soviets wanted them to see. Shaw’s characteristically fiercely critical mindset apparently was taking a vacation. He participated, at the end, in a long meeting with Joseph Stalin and reported to the British public that Stalin was “a Georgian gentleman” with no malice in him.

Back in England, at a dinner in his honor, Shaw said: “I have seen all the ‘terrors’ and I was terribly pleased by them.” In March 1933, Shaw added his signature to a letter to the Manchester Guardian disputing “misrepresentation” of Soviet achievements: “No lie is too fantastic, no slander is too stale… for employment by the more reckless elements of the British press.”

The letter said: “We the undersigned are recent visitors to the USSR… We desire to record that we saw nowhere evidence of economic slavery, privation, unemployment and cynical despair of betterment…. Everywhere we saw [a] hopeful and enthusiastic working-class… setting an example of industry and conduct which would greatly enrich us if our systems supplied our workers with any incentive to follow it.” Letter to The Manchester Guardian, 2 March 1933, signed by Shaw and 20 others.

It is painful, now, to read. Shaw had become convinced that, for the introduction of socialism, dictatorship was the only workable political arrangement. Socialism had become the absolute end; all means were “on the table.”

When the Nazis were elected in Germany in January 1933, Shaw described Hitler as “a very remarkable man, a very able man,” and professed his pride in being the sole writer in England able to be “scrupulously polite and just to Hitler.”

During the decade that the world was hurtling into disaster, Shaw and his wife, Charlotte Payne Townshend, an Irish activist and member of the Fabian Society, left their country home in Ayot St. Lawrence, Hertfordshire, to travel widely, Shaw still writing during the long spells at sea.

In March 1933, they arrived at San Francisco, Shaw’s first visit to America. He had long refused to visit “that awful country, that uncivilized place,” which he saw as “unfit to govern itself… illiberal, superstitious, crude, violent, anarchic and arbitrary.” But Shaw had advice for Americans: “You Americans are so fearful of dictators. Dictatorship is the only way in which government can accomplish anything. See what a mess democracy had led to. Why are you afraid of dictatorship?”

To my knowledge, no one has taken on the question: “Was he f—king kidding?” presumably because all evidence attests that he was not kidding. Among his legion of quotable quotes: “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.”

Shaw is referring, of course, to men viewed by their contemporaries as “unreasonable,” and the point is valid and important. Unfortunately, lauding “the unreasonable man” can also be an excuse to go on making pronouncements that are “unreasonable” and not “progress.”

With relief, Shaw sailed from New York Harbor and found New Zealand “the best country” he had ever seen. Continuing his travels in South Africa in 1935, he declared: “It is nice to go for a holiday and know that Hitler has settled everything so well in Europe.”

Still, he reserved his adoration for Stalin and championed the Soviet regime throughout the decade. In 1939, Shaw viewed the Hitler-Stalin pact (reached by Molotov and Ribbentrop) as a triumph for Stalin. Shaw said, “Herr Hitler is under the powerful thumb of Stalin, whose interest in peace is overwhelming. And everyone but myself is frightened out of his or her wits.”

Some of Shaw’s much-admired quotations could be made only by an intellectual, as characterized by Sowell.

But then, some of Shaw’s much-admired quotations could be made only by an intellectual, as characterized by Sowell. Is this Shaw, striving for clarity? “When the world goes mad, one must accept madness as sanity; since sanity is, in the last analysis, nothing but the madness on which the whole world happens to agree.” There is no objective reality; there is no objective “sanity” or “madness”; “sanity” is whatever the consensus declares and is the same as madness. To a near approximation, that also is the fundamental philosophical position of today’s “postmodernists” omnipresent in universities and the intellectual professions.

The Britannica summarizes: “Postmodernism, in Western philosophy, a late 20th-century movement characterized by broad skepticism, subjectivism, or relativism; a general suspicion of reason; and an acute sensitivity to the role of ideology in asserting and maintaining political and economic power.”

Stalin’s “Overwhelming” Interest in Peace

Just one week after Shaw’s glowingly optimistic remark, the world went “mad.” Hitler’s Panzer divisions swept into Poland from the west, and Stalin’s Red Army invaded from the east, and World War II began.

Stalin’s “interest in peace is overwhelming”? No need to observe reality to confirm that. Shaw the intellectual knew Marx’s proof that socialism is inherently peaceful. The working class in any nation, when in power—freed from their capitalist overlords—will have no incentive to war against the working class in another nation.

When the war broke out, and Poland was rapidly conquered by Hitler and Stalin, Shaw declared the war over and demanded a peace conference. Later, he conceded and urged the United States to enter the war on the side of England. During the London Blitz, the Shaws retreated to the countryside.

Shaw’s final political statement, in 1944, was a treatise, Everybody’s Political What’s What. It sold well, some 85,000 copies that year. When Hitler committed suicide in May 1945, Shaw approved the formal condolences from the Irish. He disapproved the postwar trials of the defeated Nazi leaders as mere self-righteousness on the part of the Allies. “We are all potential criminals,” he wrote.

Accountability, Reputation, and Rewards

To return again, sadder and wiser, to Thomas Sowell: “Intellectuals…are ultimately unaccountable to the external world…. Not only have intellectuals been insulated from material consequences, they have often enjoyed immunity from even a loss of reputation after having been demonstrably wrong.” In 1946, on Shaw’s 90th birthday—the tragic, bloody struggle over at last, the peril to its national existence averted—the British wished to honor him with the Order of Merit. He declined; merit should be decided by posterity.

Sowell continues: “In short, constraints which apply to people in most other fields [e.g., engineers, generals, and physicians who are judged by their results in the real world] do not apply even approximately equally to intellectuals. It would be surprising if this did not lead to different behavior.”

This, of course, is what Sowell meant when he wrote, as quoted above, “Intellectuals are ultimately unaccountable to the external world.” They give their lectures, write their articles, publish their books—interpreting the world, planning mankind’s future, telling us what we must do—and their work is done. They are paid. No crop must bloom, no patient heal, no repaired car run. All “consequences” occur at first only in the minds of followers, students, readers. Yes, that may be the story of a given intellectual’s life—but it is not the end of the story of their ideas and their consequences.

Shaw spent his last years peacefully tending his garden at his country place, Shaw’s Corner. Then, in November 1950, while he was pruning a tree (a little excursion into the “external world”), reality intervened. He fell from the ladder and later died from the internal injuries sustained. He was 94 years old, his reputation at its peak.

His idol, Stalin, died three years later at age 74. Historians estimate and re-estimate the killings that Stalin initiated or caused as leader of Soviet socialism—killings that he committed in countless, sometimes untraceable ways (planned famine, outright murder, the gulag camps)—to number at least 20 million, arguably as many as 60 million. Hitler as leader of German national socialism caused between 11 million and 17 million deaths, including of six million Jews and others in the Holocaust.