Translating deep thinking into common sense

Joseph (Book Excerpt)

By Jason Lockwood

March 21, 2016

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

The trains do run on time, even if that means they just take a lot longer to reach their destination. I’ve begun to understand the old propaganda. It didn’t consist of telling complete lies. No, there was always an element of truth, only exaggerated and inaccurate. So, the fact of transport punctuality was transformed into propaganda to make the Communists appear efficient.

I muscle my way onto the overcrowded Friday afternoon train, squeezing myself into the corridor of an overcrowded car. Outside, the temperature is in the low 50s Fahrenheit, but inside the train it feels like 90, the air redolent of stale sweat and alcohol. Barely 4:00 pm and the rabble is already drunk. Everywhere around me, people stare. I still look foreign, much as I try to blend in with my drab clothes and oversized beige jacket, which I’ve removed and slung over my arm. It must be my brightly colored purple overnight bag that gives me away. Truth be told, I’d bought it for less than $15, but it must scream Western to my train companions.

The train lurches out of the station, sending a cavalcade of already swaying passengers against me. An old lady in peasant garb snarls at me, as if I’ve done something wrong. I shrug and smile weakly at her. She harrumphs audibly, digs in her overstuffed bag, and then extracts a bruised apple, which she shoves in my free hand. She murmurs something I don’t understand, and I thank her for the apple. I have no plans to take a single bite, but she stares at me, as if to say Are you gonna eat it or what? Honor is big here, so if I don’t take a bite, I’ll have insulted her.

I take a small bite and wince. It’s mealy and overripe. She smiles. “Dobre?” I smile back. “Áno. Dobre.” “Yes, it’s good, thank you.” At this, she grabs another apple out of her bag and places it, this time gently, into my other hand. The kindness of strangers.

Two hours and 40 kilometers later, the train pulls into Bardejov station. On time. Yay Communism.

I’ve traveled hours to see my friend Rodney, who I’d met at orientation in Piešťany. He’d given me instructions in his postcard to me earlier in the week to meet him at a restaurant on the square in Bardejov. The square had recently received a nod from UNESCO for its historical import, though I’m at a loss to understand why. It’s pretty and cobblestoned, with all the appropriate quaintness of such things, but I don’t see how it’s any different from other towns just like it throughout Slovakia.

I enter the restaurant and there’s Rodney at a table near the back, already drinking a beer with a young guy who could be his student.

I approach the table and announce myself. “Hey Rodney, long time no see! How the hell are you?” I give him a clap on the back.

“Just. The train took forever.”

“We call them cow trains,” Rodney’s young friend interjects.

“Ha, it figures,” I snort.

“Jason, this is Joseph. Joseph, Jason.”

“Nice to meet you, Joseph.”

“You, too. Rodney says you haven’t traveled much since you got to Prešov.”

“Jeez, Rodney, are you telling everyone my life story?” I laugh. “Hey, how do you know Rodney? Are you a teacher, too?”

Joseph giggles. “Oh no, I’m just a student.”

“Cool. Where are you from?”

“I’m from here.”

“No, really, where in the U.S. or Canada are you from?”

“Really, I’m Slovak.”

“So you’ve lived in North America?”

“Nope, never been there.”

“Hold on a second, how come you speak with a North American accent?”

“Dunno, luck I guess,” he shrugs.

It’s all so improbable. This Joseph person can’t be older than 18 or 19 and he’s never been to the U.S. or Canada and yet he sounds like a native?

“So how do you know Rodney?”

“I don’t.”

“Rodney, help me out here. I’m confused.”

“Joseph just approached me in here. He must have heard me struggling to order.”

“Uh huh. How hard is it to say ‘pivo’ to the waiter?”

“Well, I was trying to order food…”

“I just thought he needed help,” Joseph interrupts.

“So you’re really Jozef.” I pronounce his name in Slovak—Yo-zef.

“No, I’m Joseph,” he insists.

“All right, Joseph it is. Now I need to order a beer and get some food.”

I slump into the chair to the left of Rodney and drop my bag on the floor next to me. “What’s good on the menu?” I joke.

“Well, there’s the fried cheese with tartar sauce and the fried cheese without,” Rodney answers, grinning.

“Okay, then, I really must try their fried cheese.” Joseph blinks, not grasping the humor of the situation. He is a local, after all.

Rodney then delivers the bad news: I can’t stay at his place this weekend. It turns out he had to get permission from the school before receiving guests.

“Why don’t we just break the rules? Isn’t that what Americans do? Rebel?”

“I’m Canadian, remember?”

“Whatever.”

“I still have to live here for the year. If I do that now, they might refuse me permission next time I want to invite friends to stay.”

“You’re right I’m sure. What do you think I should do?”

“There’s a motel up by the spa you could stay at. I doubt they’re full up. It’s not exactly high season.”

“Yeah, that’s probably the best option. Shouldn’t we get up there, in case they lock all the doors before too long?”

“You can stay with me,” Joseph interrupts.

“No way, I couldn’t do that. I barely know you and I’d be imposing.”

“Really, it’s okay. You can sleep on our couch.”

“Are you sure? Don’t you need to ask your parents first?” I hadn’t met a single Slovak young person who lived away from home, so my assumption of his living arrangement isn’t off base.

He shrugs, cementing his nationality.

“Okay then, if I’m staying at your place, we shouldn’t be too late, right? I don’t want you getting into trouble on my account.”

“My parents don’t care what I do,” he answers, but I’m not convinced.

“So Rodney, what’s the plan for tomorrow?”

“Why don’t you guys meet me in the square around noon and we’ll go up to the spa. There’s a restaurant up there and we can just hang.”

“Is the fried cheese as good there as it is here?”

“Ha! It’s better!” Joseph still doesn’t get the joke.

“I can’t wait. All right, let’s go, Joseph.”

“Oh, and sorry for the mix-up. I should have known.”

“This is Slovakia!” I shrug. Rodney laughs and bids us a good night. It’s nearly 10:00 pm and I can’t help wondering how this will go down with his parents, having a strange American crashing on their couch.

***

Joseph lives in a family house, as they call them here. It’s large by Slovak standards. Though its furnishings are standard issue foam and cheap wood that you find in one of the corralled areas of the Prior, everything is clean and well kept. I wonder how a Slovak family—and one with an only child—can afford to live in a house. Maybe I don’t want to know where they get their money.

Once settled in the living room, Joseph asks if I want a brandy as a nightcap. He even knows the word for it in English.

“Seriously, Joseph, how did you learn English so well? It’s uncanny.”

“I guess I’m just good at it.”

“I’m good at languages, too, but without being immersed in Belgium or Québec, I wouldn’t have perfected my French. So c’mon, what’s your secret?”

“American movies and guest lecturers.”

I do the math in my head: if he’s 19 and if the fall of Communism occurred three years ago, that means he’s had a hell of a lot of contact with Americans, and in a remote town in North Eastern Slovakia. It doesn’t add up, but like so many secret things in this country, I won’t figure them out by asking directly. And tonight, I’m too tired to press him further, however surreptitious my questioning methods.

“You definitely took advantage of the situation. Well done, buddy.”

“Don’t you want the drink?”

“What drink? Oh right, the nightcap. I should get to sleep. It’s been a long week.”

“All right.” He’s crestfallen, as if he wants to squeeze in as much time as he can speaking English with me.

“What time do you want to get up in the morning?”

“Not before 9:00, if that’s all right.”

“Sure, no problem. I will have Mom make breakfast.”

“That’s not necessary. I can fend for myself.”

“It’s not a problem. She likes it.”

“If you say so.”

He then gets up abruptly from his chair and heads to the door of the living room. “Good night, Jason.”

“Good night. See you in the morning.”

I stare at the door, confused. When we arrived, all the lights were out, with no evidence of his parents. Joseph had even made a point to do everything silently, taking off his shoes, tiptoeing across the faded carpet, pushing the door handles down slowly to avoid even the hint of a creak, then closing the doors behind him as slowly. I don’t feel welcome here.

***

The muffled argument outside the living room wakes me up the next morning. The only word I can make out as his mother scolds him is “Yozef!” Joseph indeed. He puts on a good act, but he’s just as Slovak as my students. Breakfast is out of the question.

Several minutes later, Joseph enters the living room. I’ve already dressed, packed my bag, and folded the blanket he’d given me the night before.

“My mom is angry.”

“Did you even tell her you invited someone to stay?”

“No.” He stares at his feet.

“Jeez, man, not cool. I should go.”

“No, no, it’s okay. Mom will make you breakfast.”

“Out of the question. I’m imposing. I don’t want you getting in worse trouble over me. I’ll just head over to Rodney’s. I’ll explain it to him.”

“But you don’t know how to get to his place.”

“I’ve got the address. You can tell me how to get there. He said his apartment is in a building just behind the gymnázium where he teaches. I assume there’s only one gymnázium in Bardejov?”

He grabs a pen and paper and draws me a map, using the central square as a reference point.

“That’s great, thanks. You can come along if you like.”

“I have my chores to do,” he murmurs, staring at his shoes again.

“Come hang out with us tonight, then. Meet at Rodney’s at, say, 4:00 this afternoon?”

“Okay. Maybe. I’ll see.”

“All right, Joseph, I’ll leave it up to you. You’re certainly welcome to join us.”

His mother is standing in the hallway with her arms crossed as I exit the living room, a scowl on her face. I tilt my head in a conciliatory gesture, hoping for a smile or acknowledgement. No response. I leave without saying another word to Joseph.

***

It’s 10:00 am and I’m knocking on Rodney’s door. He lives in a dirty gray industrial single-story building opposite the gray industrial school where he teaches. His apartment is at the front, with a short set of pockmarked concrete stairs leading to a door with no visible doorbell.

I wait a few minutes, then start pounding on his door. Is he even home? This weekend is turning bizarre. All I wanted was a relaxing weekend away, not the stress of worrying where I’ll sleep. Another mental note: Don’t take sleeping quarters for granted.

I don’t blame Joseph or Jozef or whatever his name is for his indulgence. He just wants a normal life, I think, where he has friends and can decide for himself how he wants to live. But he has secrets, I can tell, and secrets that might be lurid enough to put me off. I decide never to ask him too many questions. He can reveal what he wants on his own time.

After a few more minutes of knocking and waiting, Rodney finally opens the door, his eyes still foggy with sleep.

“Hey, Jason, I thought we were meeting at noon?”

“So did I, but the plan’s changed.”

He looks down, seeing my bag.

“What happened at Joseph’s?”

“Guess.”

“Parents weren’t thrilled, eh?”

“Bingo.”

“That’s a bummer. Well, come in and tell me about it.”

His apartment is huge. I’m immediately jealous. It’s got a full kitchen right inside the entrance, a long, fully furnished living room, and a bedroom with two foam and wood specials. There really is one type of bed in this country. The apartment is lived in, but not student dormitory messy.

I flop on the couch and tell Rodney the sordid tale.

“Man, people here are just weird, eh? You think Joseph will show up today?”

“I have no idea. I told him to come by at around 4:00 if he wanted to join us. I have to ask you, though. How do you think he learned his English?”

“From movies and American teachers, that’s what he told me.”

“I dunno, something about his story is off, but honestly, I couldn’t care less.”

Rodney nods.

“Hey, did you have breakfast?”

“Nope. I didn’t stick around long enough for that.”

“I’ve got some eggs and stuff, so let’s eat and then we can decide what to do. Want a turecká?”

“God, I could use a coffee. Hey, I don’t expect you to break any rules and put me up tonight. I can stay at the motel near the spa or just head home a day early.”

“Screw that. Just stay here. I’ll tell the vrátnik it was an emergency.”

“The what?”

“You haven’t learned that one yet? I guess it means night watchman or guard or something. Everything goes through him. One of my colleagues told me those guys used to be secret Party informants.”

“It figures. They’re always observing everything. It creeps me out.”

“Just imagine how it used to be!”

***

People who believe in near death experiences often talk about the urge to approach the light. The story goes that as a person is close to death, he experiences the overwhelming feeling of being drawn to a distant light source. Upon returning to consciousness, sadness sets in for the failure to reach the warm illumination where all would be better and all sins absolved.

I’ve never been a believer, but I do think the description is apt. When people have lived in a semi-dead state, it’s not surprising they’d be attracted to the fully living, even at the expense of compromising everything else.

When Joseph invited me to stay at his house, he didn’t think his mother might be angry. He acted on impulse, as if going toward the light, the light of the West beckoning him beyond the gray, industrial squalor of his Slovak life. Rodney and I were that light, as were the string of American teachers who had come before us.

After breakfast, Rodney and I head into town, on a mission to find something interesting, intriguing, or unexpected. It doesn’t take long to find it.

We approach a makeshift market in an abandoned lot near the train station. There are stalls littered around the periphery of the lot, with cheap trinkets and unappetizing food side by side. There’s no sense of order to the place, much like the odd pairings of goods in the Prior stores. We’re amused that toilet paper is on the same shelf as typing paper. Both are paper products, right?

As we make our way around the market, I notice a man swaying in our direction. I think nothing of it as we check out one cheap display after another. Then, suddenly, he’s upon us. Close up, his ethnic makeup is clear. He’s a Gypsy. I try steering us away from him, but even in his stupor he stumbles toward us.

“What the hell is this, Rodney?”

“Just ignore him. He’s too drunk to know what he’s doing,” Rodney answers under his breath.

“I don’t get it. Aren’t Gypsies normally in groups?”

“I dunno. This one I’ve seen around town on his own. He’s always like this.”

The man draws closer and starts bellowing in Romany, the Gypsy language. He stinks of sweat and stale booze.

“Rodney, whatever this guy wants, I don’t want to stick around to find out. Let’s get out of here.”

He continues his rant, attracting attention from the onlookers, attracting attention to us. He staggers forward, pointing his finger straight at my chest. He hasn’t bathed in weeks or longer, and his sour breath hits me. His incoherent rant continues till I grab Rodney’s forearm and pull him away from the scary Gypsy. “Let’s go!” I exclaim.

We turn on our heels with the man following us, but at the gait of a zombie, there’s no way he’ll catch up to us. Once at a safe distance, Rodney bursts out laughing.

“Oh, you’ve got to be kidding me!”

“What?” Rodney’s got a wide, stupid grin on his face.

“You totally set me up.”

“Okay, I’m busted.” He’s still giggling, obviously happy with himself.

“How did you know he wasn’t dangerous?!”

“Is anyone that drunk ever dangerous to anyone else? Besides, didn’t he remind you of someone?”

“Not really.”

“C’mon, really? Think about Piešťany.”

“How is Paul the Drunk Canadian like a scary Gypsy guy?”

“Because he was just as out of control half the time. Come on, you have to admit it was funny.”

“Tragic is more like it.”

“I first saw that guy like a week after I arrived in Bardejov. He yelled at me, too. Scared the hell out of me the first time. Then I figured out that’s just what he does.”

“Your idea of fun is twisted, Rodney.”

“You have to admit it was unexpected.”

“No kidding. Can we do something more expected now, like have some bad food and beer?”

“Sure, let’s go back to the restaurant on the square.”

“More fried cheese and Zlatý Bažant. Excellent.”

***

We’re sitting in Rodney’s living room, listening to music. Rodney had brought a big collection of CDs from Canada. We share a taste for quirky alternative bands. He puts on a jangly CD by the Canadian band Tragically Hip. They sing about the typical youthful angst of the day, which seems so irrelevant now that we’re living in a country full of actual angst, not the variety that young Westerners whine about. Then he puts on the first CD by Beautiful South, a group that has soaring melodies and cynical lyrics. It’s oddly comforting, listening to downer music, as I sometimes call it. The music is so loud we almost miss the boom boom boom of someone pounding on the door.

Rodney hits pause on the CD player and gets up to answer the door. Joseph shuffles in, with a beaten-down expression on his face.

“Why the face?” I ask.

“Oh, my mother is a bitch.”

“You have to admit she’s got a point. Had you told her you were having a guest, she might have been more accepting.”

“No. She’s just a bitch. Whatever, I don’t care. What are we doing?”

“Going up to the cafe near the spa,” Rodney answers.

“And drinking beer and Becherovka,” I add.

Rodney and I throw on our jackets. “Let’s go,” Rodney says. By now it’s nearly 7:00 pm and we’ve been listening to music most of the afternoon and early evening.

We trudge up the sloped hill toward the Bardejov Spa. It’s already closed for the day, but the little cafe nearby is open and already teeming with young people. Most are drinking pints of Zlatý Bažant. It’s the cheapest beer in Slovakia. It’s not bad, considering it only costs 10 Crowns, or about 35 cents. Back home it would have cost me at least two or three dollars for the same thing. It’s one of few indulgences I can afford on my 4,000-Crown-per-month wage.

For a Slovak, Joseph doesn’t drink much. As Rodney and I indulge in our pints, Joseph barely touches his.

“Hey, Joseph, you gonna keep up with us or what?” Rodney asks.

“I don’t like to drink so much,” he answers under his breath. “My Dad drinks too much.”

“All right, buddy, suit yourself.”

There’s a cheap old color TV set in the corner of the cafe and a small crowd has gathered around it.

“What’s on that’s so special?” I ask Rodney.

“It’s movie night. Let’s check it out.”

As we approach, I burst out laughing. Rodney soon joins me.

“What’s so funny?” Joseph asks.

The movie playing is Total Recall with Arnold Schwarzenegger. That’s not the funny bit. The dubbing is. The English soundtrack has only been turned down and the same voice is doing all the parts in Polish, not even Slovak, practically yelling over the original English.

“This must be a Polish bootleg,” I say.

“You can tell they had a big budget, eh?”

“I think this calls for another drink, huh Rodney?”

“Let’s make it shots of Becherovka.”

“Better watch out, I might start calling you the Drunk Canadian.”

“I’ll drink to that!” Rodney exclaims, ordering us the drinks.

Joseph sits silently, looking out of place. I almost feel sorry for him. He might speak English fluently, but he’s lost when it comes to our cultural context. Less than an hour later, as Rodney and I are polishing off another round of shots, he gets up, telling us he has to be home early or his mother will be pissed off again.

“Are you sure you don’t want to stay for another drink?” Rodney asks.

“No, I’ve had enough.”

“All right, buddy. Jas and I are gonna stick around for a while longer. Drop by next week if you want to hang out.”

“Okay,” he murmurs, turning on his heels to leave, as if to escape a bad date.

“Weird guy, eh?”

“No weirder than most people I’ve met here. There always some secret they’re not telling me. At least that’s how it appears to me.”

“I know what you mean. Does anyone tell you you’re asking too many personal questions?”

“Occasionally, yeah. What do you ask that makes people say that to you?”

“Just normal stuff about their every day lives. You know, chitchat.”

An hour or so later, Rodney and I stagger out of the cafe. We’d drunk way too much of both the beer and the Becherovka and we’re feeling no pain. As we stumble down the hill back toward town, Rodney breaks into song. I shush him at first, noting how loud he’s getting. Then my inebriation really kicks in and I join him. I dread the next morning.

***

When I get on the train home the next afternoon, my head is still throbbing from the previous night’s overindulgence.

Neither of us sees Joseph again during the weekend. He’d disappeared just as he’d entered our lives: silent and surreptitious. I think about him as the train chugs along the tracks, back toward Prešov. I wonder who he really is, this kid born in a messy and irrational country, still picking through the rubble, desperate for contact with the world Rodney and I inhabit.

The next time I see Joseph, he’s waiting for a train in Prešov a week later. It’s odd, seeing him alone and forlorn like that, as if he can’t wait to escape something. He’s got a small canvas bag slung over his bony left shoulder. He’s staring into space, smoking a cigarette. I hadn’t noticed that he smoked before, so this is something new. I approach him, asking him if he’s on the next train to Bratislava. He nods.

After we both get off the train at Bratislava, I ask him where he’s headed, and he mumbles something I don’t understand. He then repeats that he’s going to stay with his aunt in Petržalka.

“Great, maybe I’ll see you around over the weekend. I’m staying there, too.”

“At my aunt’s?” he asks with a quizzical expression on his face.

“No, in Petržalka. My friends live there.”

“Okay, see you around maybe.”

He walks off toward the bus stop near the train station entrance.

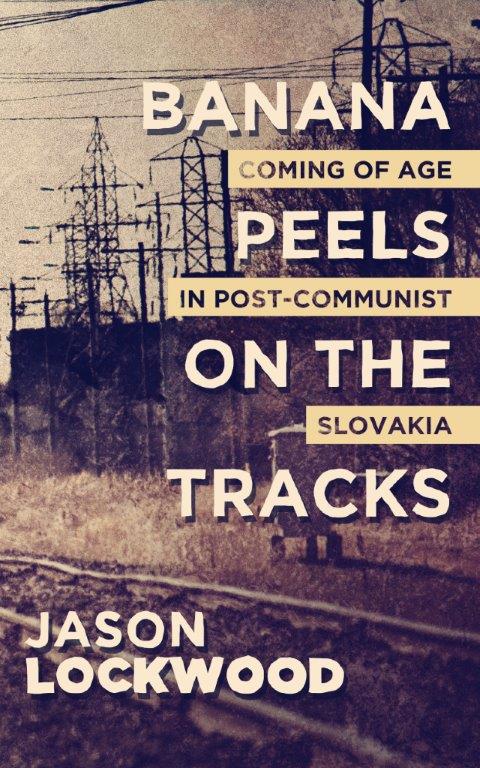

This excerpt is Chapter 5 in the book, Banana Peels on the Tracks, a memoir chronicling Jason Lockwood’s experiences in former Communist Slovakia in 1992-93.