Translating deep thinking into common sense

Magic’s Measure in the Age of Science

By Walter Donway

November 9, 2021

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

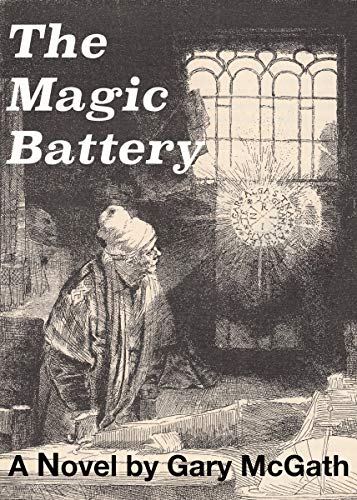

What breed of author does it take to write, today, a novel about “magic” and “mages” that warrants the characterization “one of a kind”? There are no rings, here, no dragons, no soaring boy wizards. Gary McGath has given his first novel the title, The Magic Battery. If you consider that today’s entire trend toward solar power, for example, and electric cars, depends upon the quality of battery technology, then this magic is eerily contemporary.

But The Magic Battery, written by an abundantly experienced writer in fields of technology and much else, is set in Sixteenth Century Saxony (later a part of Germany). The “magic” is not imaginary as in today’s fantasies, it is real. Or more literally, it is magic as understood, practiced, and debated in the later Middle Ages in Middle Europe.

McGath introduces the novel as “fantasy,” but he treats magic in the story itself as seriously as any science.

You see some of the complexity and playfulness of this novel, here. McGath introduces the novel as “fantasy,” but he treats magic in the story itself as seriously as any science. Many at that time thought it so. Another twist? The novel begins with an explanation that but for Thomas Lorenz and his efforts in the Sixteenth Century, the world today would not be living on Mars.

Got it? Thomas Lorenz is apprenticed to a professional mage, a member of the official guild of mages, along with another apprentice, Michael. His expectation is to serve his master, learn magic, master its limits, pass the examination by the Mage’s Guild, and go into practice for himself. This is broadly historically accurate. For centuries, magic had been practiced as a profession, or adjunct to a profession, such as healing. Surgeons, midwives, and other healers resorted to magic, often for strictly delimited purposes. In its treatment of magic, the Catholic Church, evolved over centuries.

But the Sixteenth Century was the height of the Protestant Reformation, especially in Germany, and its prophet was Martin Luther.

But the Sixteenth Century was the height of the Protestant Reformation, especially in Germany, and its prophet was Martin Luther. Many distinctions among “magicians” no longer were recognized because Luther viewed the power of magic as commerce with demons. The ultimate penalty for what became known as “witchcraft” was burning at the stake. And hundreds of women burned.

But distinctions were drawn. Christian males were trusted to employ magic without invoking demons and Satan or accidentally blowing up something. For the same magic, women and Jews could die.

In this tumultuous era of change, The Magic Battery begins. The apprentice, Thomas, assigned to copy an old manuscript, becomes excited about an idea that parallels the insights of the age. Could magic, even if from another world, be a force like all those in our world—seemingly causeless, impenetrable, but ultimately explainable by science? It gets more specific. Might the mystery of magic, as another energy, yield to the new power of mathematics? McGath has imagined that one of the deepest mysteries facing the emerging Age of Science might be attacked by the tools of Newton and Copernicus.

The relationship between master and apprentice is fully imagined and intriguing. Apparently teaching magic spells can be frustrating; you don’t describe casting a spell, you let the apprentice sense the spell and try to imitate it. This means the apprentice must have a natural aptitude for magic. Thomas sometimes gets involved in the master’s spell too soon, earning a groan of frustration, or a cuff, from the master.

In an age when the missteps of the mage might end at the stake, Thomas bores into the manuscript. It intrigues and eludes him. Then, the author of the manuscript, a man on the run much of his life, shows up. He is Johan Faust, the era’s object of fear, fascination, legend, and puppet show farces—the “doctor” imagined to have rejected theology to trade his soul with the devil in exchange for human knowledge and life’s worldly pleasures.

This becomes a master-apprentice interaction on a whole new level. Johan Faust, of course, has been demonized by the world merely for mastery of magic. He is a great soul, a man who lives and dies with a laugh at the beauty and folly of the world. Thomas against all odds studies the mathematics needed to pursue the “next big thing” in magic. Can the real-time power of a mage’s spell be stored in a device? If so, not only certified Christian male mages will benefit from magic. Its power will become available to all: its power to heal, to light, and to multiply energy for work. “It’s a science. The World Behind is part of nature.…” We watch Thomas pursuing his theory and the technology it implies. “Every mage used a crystal to focus magic, and its effectiveness depended on its material and its shape.…” “All that is necessary is the right mathematical insight, but it keeps eluding me.”

The Magic Battery is not a thriller, nor a mystery, but it has elements of both.

The Magic Battery is not a thriller, nor a mystery, but it has elements of both. It is historical fiction best described as deeply engrossing. In a sense, it is rarely highly inflected, rarely becomes violently dramatic. A rare exception is when a midwife, mother of the girl Thomas marries, and who has used her healing powers to ease hundreds of births, is arrested as a witch. She faces torture but precipitates her escape from torture and burning by terrifying her interrogators with a fully blown satire on “satanic magic.” In a panic, they kill her.

The force behind these horrors is the Lutheran lawyer and inquisitor, Heinrich Gottesmann, who from the outset is the Lutheran champion, relentlessly rooting out and destroying deviant mages, all women practitioners (including all the healers), and all Jews and other dupes of the devil. McGath, like great Romanticist novelists such as Victor Hugo, pits moral hero against moral hero, as Javert in Les Miserables is pitted against Jean Valjean.

Gottesmann is more dangerous because of his genuine passion for his work, which regretfully requires torture and burning. “Torture is a great blessing for one whose soul it redeemed.” He “had grown up determined to stop the spread of witchcraft.… There was so much nonsense on the subject. He had read a book called Malleus Maleficarum…[the leading authority in the Middle Ages on witches]. It Was superstitious absurdity from beginning to end.”

Gottesmann is more dangerous because of his genuine passion for his work, which regretfully requires torture and burning. “Torture is a great blessing for one whose soul it redeemed.” He “had grown up determined to stop the spread of witchcraft.… There was so much nonsense on the subject. He had read a book called Malleus Maleficarum…[the leading authority in the Middle Ages on witches]. It Was superstitious absurdity from beginning to end.”

The characters in The Magic Battery—as Thomas overcomes his shyness to meet and marry—are his wife, Frieda, who discovers her intellect and her passion for justice. And Johan Faust’s son, who arrives seeking knowledge of the father he never knew. And a Jewish investor, Yonah David, who supports Thomas’s prosperous business of creating instruments that work on stored magic power. His backer views Thomas’s work as the normalization of magic—one step further away from religious bigotry.

These have the feel of “ordinary people,” sometimes doubtful, sometimes hopeful, sometimes fearful, who are undaunted seekers of the new science abroad in the world. They see the religious dogma, persecution, and blindness to reality of the hounds of Luther for what they are. They resist: Thomas in his work on new devices, Frieda in writing and publishing a challenge of reason and science to dogmatic misogyny, and the son of Faust in getting the book published and carrying the message to the world.

In very general terms, the reader sees the climax coming. The novel moves forward by powerful logic and a stark conflict. But the outcome is not predictable. The ultimate sanction of the age against unapproved magic is burning at the stake. Thomas Lorenz will not forsake his advancement of magic, nor will Frieda. Even with the arrival of a baby, she says: “Being afraid of them won’t make us any safer. It’s time to take a different course.”

The fiercely determined Heinrich Gottesmann manages to bring Thomas to court on charges of the irresponsible use of magic that can threaten the world. In part, Gottesmann is driven by rage at the book that Frieda Lorenz anonymously has published and now is sweeping Germany.

In the climactic court scene, Thomas Lorenz stands accused and Gottesmann is the prosecutor. Soon, Frieda refuses to remain silent and stands beside him.

It comes at an inflection point in European history. The shattering scientific demonstration of Copernicus that the earth revolves around the sun is still heresy. But a secular tide later called the Age of Enlightenment, or the Age of Reason, is fermenting in its early stages. The anonymous book by Frieda is inspiring groups of women across Saxony, and beyond, to meet to challenge the age-old misogyny of religion.

This is one of a kind. I recommend it without reservation.

When the judge sums up the conflicting testimony of Lorenz and Gottesmann, the age is judging itself. The considerations may be legal and secular or impassioned appeals to Lutheran dogma and the specter of demons loosed on the world.

This extraordinary self-published novel by a lifelong writer is flawless in its mechanics. The story in all its subtlety, depth, and human drama is told in a lucid style without distractions in the text. The Magic Battery rises to the level of a new classic on the themes of reason versus dogma, science versus faith, and human courage and hope versus terror of the unknown. And as with genuine literature, the texture of incidents, actions, and characters only can be hinted in a review.

This is one of a kind. I recommend it without reservation and with certainty that it should reach a wide and very lucky readership.