Translating deep thinking into common sense

Objectivism and Individualistic Perfectionism: A Comparison

By Edward W. Younkins

October 19, 2023

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Editor’s Note: Some of the claims made about Objectivism in this essay are not accepted by any of the editors of Savvy Street and are disputed.

The purpose of this pedagogical essay is to compare the ideas of Ayn Rand with those of Douglas B. Rasmussen and Douglas J. Den Uyl (frequently referred to as the two Dougs). Both Rand’s philosophy of Objectivism (O) and the Dougs’ philosophy of Individualistic Perfectionism (IP) can be considered to be neo-Aristotelian philosophies (1). While Aristotle should not be described as a classical liberal, his ideas have influenced Rand as well as the Dougs.

While Aristotle should not be described as a classical liberal, his ideas have influenced Rand as well as the Dougs.

Aristotle has sometimes been interpreted to support statism, natural slavery, and sexism, and, therefore, could be considered to be illiberal. He sometimes cited the need to have the state to force men to be virtuous via laws and punishments. Despite this, his ideas on reality; knowledge; the teleological nature of human beings, the human good, and morality; rights; and happiness as attained through virtuous actions have influenced both Rand and the Dougs who have argued that such Aristotelian ideas could support a classical liberal position. After explaining, discussing, comparing, and contrasting the ideas of Rand and the Dougs, toward the end of this essay, Exhibit I will provide a summary comparison of their ideas based on a variety of factors and dimensions on which they differ.

According to Rand, reality is objective and absolute and human beings are competent to achieve objectively valid knowledge of that which exists. Knowledge is based on observation of reality. Through both introspection and extrospection, a man produces knowledge using the methods of induction, deduction, differentiation, and integration. In O’s metaphysics and epistemology A is A, reality is knowable, and individuals can develop objective concepts that correspond with reality. Although concepts and definitions are in one’s mind, they are not arbitrary because they reflect reality which is objective. Rand asserts that essences and concepts are epistemological, contextual, and relational, rather than metaphysical. (2)

Likewise, Rasmussen and Den Uyl assert that there are things and beings that exist, and are what they are independent of human cognition.

Likewise, Rasmussen and Den Uyl assert that there are things and beings that exist, and are what they are independent of human cognition, but these things and beings can be known. Further, the nature of these beings is the standard for both descriptive and evaluative cognition and does not depend upon being cognized to either exist or be what it is. The products of cognition—that is, concepts, propositions, and arguments—should not be conflated with reality. Cognition is of reality but it is not reality. There is a difference between something as it exists independent of cognition, for example, (3) what is valuable, and as it exists in cognition. IP’s metaphysical realism holds that there are things that exist and what they are is distinct from our cognition of them.

For Rand, the existence of the good (as in, valuable) requires that it is thought about and found to be desirable.

Rand states that life is conditional, the basic alternative is existence versus non-existence, the requirements of a man’s survival are determined by reality, and that the good is an aspect of reality that has a positive relationship to a man’s life. There is an association between ultimate ends and values and facts of reality. She understands that value judgments could be objective based on a correct relationship between a person’s mind and the facts. What is good or bad refers to the relationship between some feature of reality and the life of a living thing. For Objectivism, the good is an evaluation of the facts of reality by a man’s consciousness according to a rational standard of value. For Rand, the existence of the good (as in, valuable) requires that it is thought about and found to be desirable—it requires a cognitive act in order for its “value” to exist. Rand seems to call for the conceptual recognition of what is valuable or good in order for it to exist in reality as something potentially valuable to, or good for, a given person.

Under O, one’s theory of knowledge necessarily includes a theory of concepts and one’s theory of concepts determines one’s concept of value (and ethics). The key to understanding ethics is in the concept of value and thus is ultimately located in epistemology and metaphysics. For Rand, the concept of value depends upon, and is derived from, the antecedent concept of life, which she explains, is the ultimate value. Derivative values exist in a value chain, network, or hierarchy in which every value (except the ultimate value) leads to other values and thus serves as both an end and a means.

The Dougs, however, emphasize that the good exists in reality apart from, and independent of, human cognition.

The Dougs, however, emphasize that the good exists in reality apart from, and independent of, human cognition. To repeat, there is a difference between one’s knowledge of what is good and the reality that supplies the basis for that knowledge. Rather than being a concept, the good for a human being is an individualized reality that conveys the potential to be actualized. The concept of the human good should not be confused with its reality. The individual human good or telos exists as a potentiality that does not depend upon it being cognized to exist or to be what it is. The good is a feature of reality in relation to an individual human person. Potential values are related facts of existence. The relationship between a potential value and an agent’s life is metaphysically given. “Good for” is a relational term and refers to what is desirable, worth-wanting, or worth-doing for the sake of an individual person. The individual human good is discovered or realized, rather than constructed. For IP, involvement in the act of ascertaining the human good is itself also good for a human person.

Rand defined logic as the act of non-contradictory identification. It is the human method of reaching conclusions objectively by deriving them, without contradiction, from the facts of reality. She explains that concepts are valid when they are integrated, without contradiction, into the sum of a person’s knowledge. All truths are the products of the logical identification of the facts of existence. Similarly, the Dougs define logic as the method by which a volitional consciousness conforms to reality. The method of logic reflects the nature and needs of man’s consciousness, his free will, and the facts of reality.

According to Rasmussen and Den Uyl (paraphrased):

Rand did not always keep clear the distinction between logic and reality. This failure led her to make an error regarding the basis for moral values. Things of existence have a nature or identity, these can be known, and the method of logic is defined by the laws of reality. Rand said little about the nature of logic or its tools that allow it to function as the guide for human cognition.

The Dougs state that the objects that logic studies are not the same as the things that exist and have a nature apart from human cognition. Concepts, propositions, and arguments are of, or about, reality, yet there is a difference between them and reality. As noted above, Rand holds that the good is an evaluation of the facts of reality by man’s consciousness according to a rational standard of values. It follows that the good does not exist if no one makes an evaluation. By IP standards, she should have said “The concept of the good…”

Thus, the Dougs maintain that (paraphrased):

Rand did not fully appreciate that the human good, as it actually exists in reality is itself something that is individualized. Nor is there a discussion of the relation of potentiality or the recognition of grades of actuality with the first grade of actuality being a cognitive-independent reality. Another example of her failure to keep the distinction between logic and reality clear is when she refers to her “objective theory of value.” She should have said “theory of objective value.”

For Objectivism, the acts of thinking, acting, and flourishing are embedded in the more basic act of choosing. Rand contends that a person needs to choose to live in order for ethical obligations to exist. If a person chooses to live, then a rational ethics will inform him what actions are needed to put his choices into action. She seems to be implying that people who do not make the fundamental choice to live do not have the obligation to be moral (i.e., rational).

In Individualistic Perfectionism, there is a realistic basis for one’s responsibility to choose to live as the potential flourishing rational being that one is. Each person is responsible for making a life for oneself. According to the Dougs, one’s life as a flourishing being is desired because it is, in itself, desirable and choiceworthy. They explain that, under O, there are no oughts, normative standards, or ontological realities that underpin the choice to live. IP agrees with O that life is the ultimate end, value, or standard for a human person. However, IP has a problem with Objectivism’s lack of a normative reason for making the choice to live. If there is no moral obligation to live, then the choice is ultimately discretionary or optional. Thus, under O, if an individual does not choose to live, then he is outside the sphere of morality.

Rand states that a right is a moral principle defining and sanctioning a man’s freedom of action in a social context. She says that individual rights can be derived from man’s nature and needs and she approaches the derivation of natural rights by way of ethical egoism. For her, rights are a moral concept. Although Rand’s rights are of a negative nature, she speaks of them in a positive way (i.e., of a person’s freedom to act on his own judgment by his own uncoerced voluntary choice). Each person has the ability to think his own thoughts and direct his own energies in his efforts to act according to those thoughts.

According to IP, natural rights are metanormative principles that regulate the conditions under which human action takes place in society. The individual right to liberty secures the possibility of self-directedness, and thus the possibility of moral conduct and human flourishing in a social context. The Dougs distinguish between the function of ethical theory at the normative level and the function of ethical theory at the metanormative (i.e., political) level. Equinormativity is false—not all ethical norms have the same function. While they do not want to include a normative account of human beings into a theory of political organization, their politics does presuppose a theory of human nature and the human good. They explain the need for a different type (or level) of ethical norms when social life is viewed as dealing with relationships between any possible human beings, and when the individualized makeup of human flourishing is understood. The goal of the right to liberty is to secure individuals’ self-direction which, in turn, allows for the possibility of human flourishing.

IP sees a problem in what O calls a moral principle (i.e., individual rights) as the subject of political action and control. The Dougs’ goal is to abandon the idea that politics is institutionalized ethics. They say that statecraft is not soulcraft, and that politics is not an appropriate method to make men moral. They proclaim the need to divest substantive morality from politics. The purpose of liberalism, as a political doctrine, is to secure a peaceful and orderly free society. They explain that “rights” is an ethical concept that is not directly concerned with human flourishing, but rather is concerned with context-setting—establishing a political/legal order that will not require one form of human flourishing to be preferred over any other form. IP’s explanation of rights and human flourishing necessitates that cognitive realism is true—a realist turn (one in which rights are based on the natural order of things) is required to produce a proper and comprehensive defense of freedom.

The IP approach contends that moral norms are not all of the same type. Some provide a context within which moral actions can occur whereas there are other norms that provide guidance toward attaining an individual’s good. A two-level ethical structure consists of ethical metanorms (also referred to as political/legal norms) and personal/social ethical norms. Rights, as metanormative principles, supply guidance in the formulation of a constitution whereby the legal system establishes the political and social conditions required for persons to select and implement the principles of normative morality in their individual lives. Both metanorms and norms depend upon an understanding of human nature.

Rand explicitly argues for only one sense of interpersonal justice—normative justice (the metanormative can only be gleaned from her comments on law). She explains that justice is rationality in the evaluation of human beings. It is necessary to judge each person’s character and actions and to grant each person what he or she deserves in a given context. Judgments should be made on the basis of all the factual evidence and the evaluation of it by means of objective moral criteria. Justice requires rewarding people whose actions objectively advance or preserve men’s lives rather than those whose actions diminish their lives. It is essential to use reason to reach moral estimations and to pronounce moral judgments. For O it is also important to judge oneself according to the same rational standards that one uses to judge other people. It is necessary to judge other people because individuals have the potential to be values or disvalues to others. According to Rand, the ultimate purpose of pronouncing moral judgment is the enhancement of the agent’s own life.

Conversely, the Dougs explicitly argue for two senses of interpersonal justice. One is normative justice toward others as a constituent virtue of one’s own personal flourishing and the other is metanormative justice which is concerned with the orderly and peaceful coordination of any person’s actions with those of any other. This latter type of justice deals with nonexclusive, universal, and open-ended relationships, thus providing the foundation of a political order as well as the context for exclusive relationships to develop and for the possibility of personal flourishing and happiness. This type of justice is not concerned with the exercise of virtue but rather creates a place for it. Justice as a normative principle and constituent virtue involves a person’s contextual recognition and evaluation of others based on objective criteria. Normative justice is concerned with selective (i.e., exclusive) relationships and requires practical reason and discernment of both persons and situations.

Rand’s explanation of government requires that individuals delegate the protection of their rights to an institution that holds a monopoly on the use of retaliatory force. Individual moral consent must be given to the principle of renouncing the use of force and delegating the right of physical self-defense to the government which has specific and clearly defined powers. She does not subscribe to social contract theory per se in which individuals purportedly consent to government authority. For Objectivism, the delegation of rights is a moral requirement rather than a claim about assent to a specific institution. Because O does not contend that government arises from an act of express or tacit consent, it rejects the statist suggestions of consent theory.

The Dougs distinguish between substantive and procedural contractarianism. They reject the former and employ the latter as a heuristic device to explain how people might develop a constitutional contract (as James Buchanan describes it in his work, The Limits of Liberty). The use of procedural social contract theory is for the purpose of showing that attaining a rights-based limited government is a realistic goal and not mere idealism. They make a point of saying that Buchanan’s theory requires a normative basis from rights and that consent is not the ethical foundation. IP’s argument for rights makes no appeal to a so-called state of nature that is supposed to be an asocial context in which human beings live or that serves as a basis for an account of ethics as ultimately a matter of argument or convention.

According to Rand, there is no common good (or public interest) that exists over and above the state’s moral obligation to protect each person’s rights. There is no such thing as the common good other than the sum of individual interests of individual citizens. Similarly, the Dougs assert that the state can properly be said to be ensuring the common good when it protects man’s natural right to seek his own happiness—only protected self-directedness can be said to be good for, and able to be possessed by, all persons simultaneously.

According to Rand, law must be objective, justifiable, impartial, consistent, intelligible, and must be derived from the principle of individual rights. For O, that which cannot be formulated into objective law cannot be made into the subject of litigation. Similarly, the Dougs explain the rights are the basis upon which a legal system must be developed, and that, if the laws of a legal system are to be equally and universally implemented, then these rights must be a type of moral principle applied to each and every human being in a social context regardless of that person’s particular needs, goals, or circumstances. For IP, law must pertain to everyone and so the duty legally demanded of others by a right must result from those characteristics of human life that everyone shares.

For Rand, the acceptance of full responsibility for one’s choices, actions, and their consequences is a demanding moral discipline that should not be escaped from by turning to what can be seen as the easy, automatic, and unthinking morality of duty. Each independent person has the responsibility of judgment. Those who reject the responsibility of thought and reason can only exist by freeloading on the thinking of others.

Rasmussen and Den Uyl propose two templates for analyzing ethical theory—the template of respect and the template of responsibility. These templates are not two theories of ethics, but rather are frameworks within which moral theory occurs. IP advocates the template of responsibility for one’s self-perfection. The Dougs anchor moral values in the details of exercising agency instead of in abstract conceptions owing their objectivity to universality. The template of responsibility is agent-centered and begins by recognizing the existential conditions that each responsible and choosing person must make a life for himself. It follows that moral action must be individualistic rather than generic or communal.

Rand and the Dougs have distinct perspectives on natural law. Rand rejects the traditional notion of natural law. O centers on rational self-interest and rejects the notion of innate moral laws. For Rand, morality is derived from reality, reason, rational self-interest, and individual rights, not from an external source like natural law. IP emphasizes the importance of natural law as a foundation for objective legal and moral principles. The Dougs also assert that the nature of human beings and the world provides a basis for identifying universal moral truths. They argue that the nature of the individual human being provides the standard or measure for determining the morally worthwhile life and the basis for individual rights.

Rand’s rational objective moral theory is based on reality, reason, and egoism. The goals of morality for O are that the agent should always be the beneficiary of his actions and that a person should act for his rational self-interest. Objectivism considers the relationship between an individual and his self as the main consideration of normative ethics. For IP the central question of normative ethics is not a matter of whether a not a person is acting for one’s own benefit or for the benefit of others but instead what type of self that one is making—the Dougs do not make the relationship to the beneficiary paramount.

Moral theory for both O and IP is based on the Aristotelian idea that the objective and natural end for a human being is his flourishing. The teleological nature of individual living beings involves their potential to develop to maturity. All human persons have the inherent potential to develop to their mature state (i.e., to flourish). To live one’s life as a flourishing rational animal is one’s telos, ultimate goal, or final value. This final value establishes the standard by which all subordinate goals are means.

The Dougs state that there are both generic and individual potentialities and that the basic or generic goods and virtues are a bundle of capabilities the realization of which is needed for personal flourishing, but the form of which is individualized by each man’s character, interests, and circumstances. The constituent virtues must be applied, although differentially, by each person in the task of his self-actualization. Virtues and goods are the means to values and the virtues, goods, and values together enable human beings to pursue their flourishing and happiness. Self-perfection becomes real and determinate when the generic virtues and goods are expressed through an individual’s unique talents, potentialities, and circumstances. Under IP human flourishing is objective, inclusive, individualized, agent-relative, self-directed, and social. According to IP, life has a nature that always and necessarily involves a specific form of living. One’s potential for human flourishing is a reality independent of one’s cognition that is always expressed in individualized form.

Objectivism’s account of ethics includes the virtues of rationality, independence, integrity, honesty, justice, productiveness, and pride. Rand explains that rationality is the master virtue and that all of the derivative virtues are integrated and interdependent—all are aspects of rationality applied and viewed within more limited contexts. For O, these virtues are causally contributive to a person’s survival and flourishing.

Individualistic Perfectionism adds virtues such as practical wisdom (prudence), benevolence, temperance, courage and so on to the Objectivist list of virtues.

Individualistic Perfectionism adds virtues such as practical wisdom (prudence), benevolence, temperance, courage and so on to the Objectivist list of virtues. The Dougs explain that practical reason is a self-directing activity and that practical wisdom is the excellent use of practical reason. They maintain that practical wisdom is the central integrating virtue of a flourishing life. Practical wisdom is the intellectual faculty for judging the best course of action for particular individuals in specific circumstances. In addition, they make a case that the virtues both causally contribute to and constitute the flourishing of a human being. Rand does not mention practical wisdom and views the virtues as only instrumental.

Rand maintained that one should only help strangers in emergencies but not at the risk of your own life. She also said that it can be proper to help someone who is ill or poor, if you can afford it. In addition, routine kindnesses are called for according to the ways that others are to be valued with respect to social relationships. Rand has been criticized for inadequately recognizing the social nature of human beings and having little to say about human relationships, family, childrearing, and voluntary associations. However, Objectivism does view benevolence, the value of personal relationships, as based on shared values. Holding that there is a fundamental harmony among rational people, O explains that each individual can create values that can enrich the lives of everyone else. Goodwill toward others is an accompanying ingredient of rational egoism. Valuing other people and their potential to develop is viewed as an extension of one’s self-esteem. It is possible to incorporate another individual’s interest into one’s own hierarchy of values.

Under IP’s thicker theory of the human person, social interactions and associations offer great benefits to individuals including friendships, more information, specialization and division of labor, greater productivity, a larger variety of goods and services, etc. In addition, the Dougs explain that a person’s moral maturation requires a life with others. Charitable conduct can therefore be viewed as an expression of one’s self-perfection. From this viewpoint, the obligation for charity is that the benefactor owes it to himself, not to the recipients. Charitable actions may be viewed as perfective of a person’s capacity for cooperation and as a particular manifestation of that capacity. Kindness and benevolence, as a basic way of functioning, is not an impulse or an obligation to others, but rather is a rational goal. This nonaltruistic, noncommunitarian view of charity (and other virtues) is grounded on a self-perfective framework under which persons can vary the type, amount, and object of their charity based on their values and contingent circumstances.

Rand held that there are no conflicts of interests among people who form and pursue their values rationally and objectively. For O differences among individuals cannot lead to legitimate conflicts between persons with respect to their particular, personal good and the actions they should take.

According to the Dougs, because one individual’s concrete form of flourishing is not the same as another person’s, there is a possibility of what they call “righteous conflict.”

According to the Dougs, because one individual’s concrete form of flourishing is not the same as another person’s, there is a possibility of what they call “righteous conflict.” They explain that to classify a virtue as rational is not to assume that it exists in the same manner and to the same degree for different individuals. IP contends that, as a matter of principle, the potential for legitimate disputes between individuals, with respect to their specific individual good, cannot be dismissed.

The Dougs state that Rand offers little or no discussion of how one is to differentiate one’s individual moral goodness from that of another. She says little about how the contingencies particularities, and subtleties of situations impinge upon individual moral decision making.

Rand explains that progress through science and technology is the result of the human ability to think conceptually and to analyze logically. Progress is based on the power of human reason and conscious thought. Man has the ability to adapt nature to meet his requirements. In The Fountainhead, she shows that the basic needs of a creator are independence, individuality, and vision, the courage of one’s convictions, living a value-driven life, and a drive toward action. These are the essential attributes of an entrepreneur.

IP sees progress as closely tied to individualism, freedom, human potential, and a market-based society. Progress occurs when individuals are free to pursue their own goals, make choices, and engage in voluntary transactions. The Dougs’ ideas about progress are about the growth of opportunities to obtain the goods and values for individual human flourishing.

The Dougs discuss the creativity of the human person both in producing wealth and in making moral character, two activities that are ingredients of a flourishing life. Both of these activities require openness and alertness and apply to virtually any kind of human activity. Both entail an insightful and evaluational approach to living one’s life. The goal of both is integrity of action. Earning profit can be a legitimate form of ethical expression. Discovery and evaluation are key ideas in both entrepreneurship and ethics. Economic wealth and ethical wealth are both functions of the degree to which individuals produce good lives.

Aristotle is Ayn Rand’s only acknowledged philosophical influence. However, it can be said that she respected, and was likely affected by the thinking of others such as Thomas Aquinas, Brand Blanshard, Hugo Grotius, John Locke, Montesquieu, Friederich Nietzsche, and Baruch Spinoza,, among others.

Aristotle has also been a great influence on Rasmussen and Den Uyl. Other important influences on them include Thomas Aquinas, Ayn Rand, Henry B. Veatch, David L. Norton, Phillipa Foot, and certain Austrian economists such as Ludwig von Mises and Murray Rothbard.

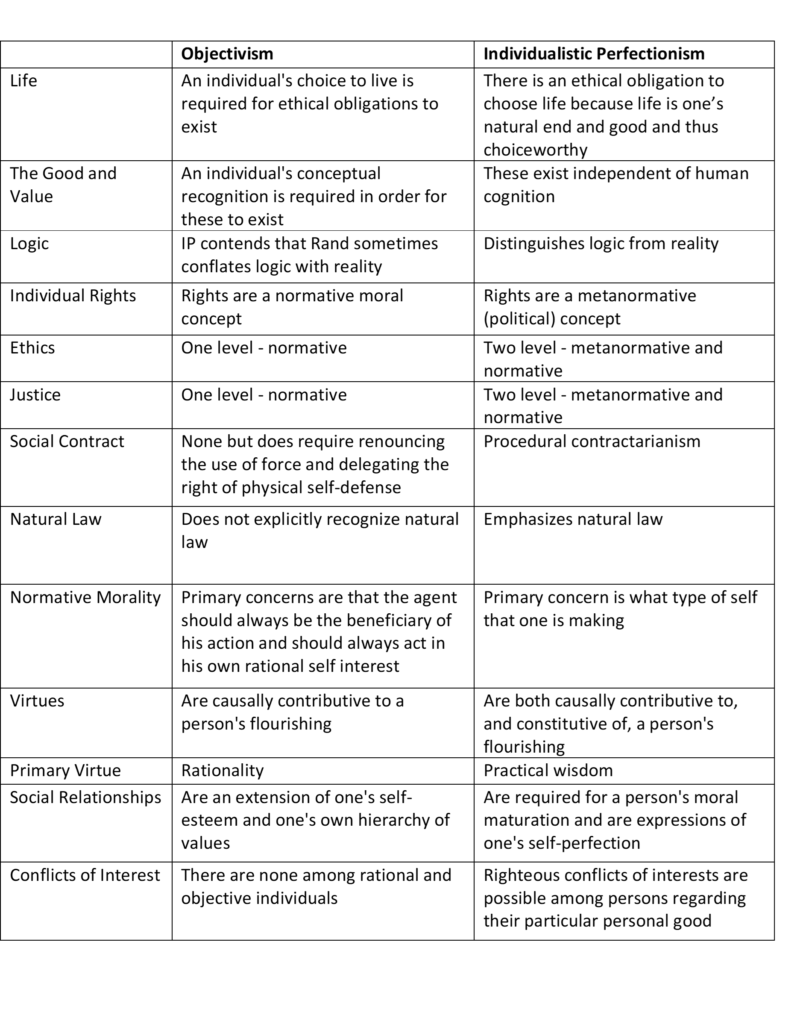

The purpose of this essay has been mainly descriptive and explanatory. Exhibit I provides a side-by-side summary of the differences between Objectivism and Individualistic Perfectionism on a number of issues. Not included are topics on which they are in substantive agreement such as reality, free will, common good, law, responsibility, and progress.

Although Rand and the Dougs differ on how a number of issues are expressed, they agree on the desirability of a free society and are among the best-known proponents of capitalism from a neo-Aristotelian perspective. Their works are highly recommended for any student of liberty.

Notes

- A philosophy can be thought to be neo-Aristotelian (i.e., in the tradition of Aristotle) if it: (1) incorporates some essential doctrines of Aristotle; (2) uses Aristotelian ideas as a starting point for further philosophizing; (3) uses Aristotelian ideas within a new intellectual context; (4) uses Aristotelian ideas or perspectives in the service of arguments that stand on their own merits; (5) views Aristotelian ideas as a source of inspiration and insight; or (6) applies Aristotelian ideas to contexts not foreseen by him (Miller (1995), Skoble (2023), and Massimino (2023).

- Ayn Rand’s philosophical approach has often been likened to the broad-brush strokes of an artist, but lacking the minute strokes needed to thoroughly complete a painting. Her writings lack the attention to details, contexts, examples, and counterexamples that are the trademarks of scholarly philosophers. She did not provide proof or validation of all of her Objectivist concepts and principles themselves. A nuanced examination of these details is beyond the scope of this short essay. Her views in areas such as the nature of reality and its relation to thought, the objectivity of concepts and propositions, essences as epistemological, etc., need to be studied in more depth than has been done to date.

- The words “the concept of,” which originally appeared at this location, were inadvertently included and are in contradiction to what I actually had to say on the matter. My apologies to early readers and to Roger Bissell who consented to delete the paragraph in his essay that challenged what I had originally written.

Exhibit I

Summary Comparison of Differences

Bissell, Roger E. 2020. Eudaimon in the Rough: Perfecting Rand’s Ethics. The Journal of Ayn

Rand Studies 20 (2): 452-78.

Den Uyl, Douglas J. 1991. The Virtue of Prudence. New York: Peter Lang.

_____. 1992. Teleology and agent-centeredness. In The Monist 75 no.1 (January), 14-33.

_____. 1993. The right to welfare and the virtue of charity. Social Philosophy and Policy 10, no. 1 (Winter): 192–224.

Den Uyl, Douglas J. and Douglas B. Rasmussen, eds. 1984. The Philosophic Thought of Ayn Rand. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Den Uyl, Douglas J. and Douglas B. Rasmussen. 1995. Rights as metanormative principles. In Liberty for the Twenty-First Century, edited by Tibor R. Machan and Douglas B. Rasmussen. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

_____. 2016. The Perfectionist Turn: From Metanorms to Metaethics. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Massimino, Corey. 2023. Ayn Rand’s Novel Contribution: Aristotelian Liberalism. The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies 23 (1-2): 314-327.

Miller, Fred D. 1995. Nature Justice, and Rights in Aristotle’s Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Peikoff, Leonard. 1991. Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand. New York: Dutton.

Rand, Ayn. 1957. Atlas Shrugged.New York: Random House.

_____. 1964. The Virtue of Selfishness: A New Concept of Egoism. New York: New American

Library.

_____. 1966. Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal. New York: New American Library.

_____. 1979. Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology. New York; The Objectivist.

Rasmussen, Douglas B. 1999. Human flourishing and the appeal to human nature. Social Philosophy and Philosophy (1–43).

_____. 2002. Rand on obligation and value. The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies 4, no. 1 (Fall): 69–86.

_____. 2006. Regarding choice and the foundation of morality. The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies 7, no. 2 (Spring): 309–28).

_____. 2007. The Aristotelian significance of the section titles of Atlas Shrugged. In Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged: A Philosophical and Literary Companion. Edited by Edward W. Younkins. Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 33–45.

_____. 2014. Grounding necessary truth in the nature of things: a redux. In Shifting the Paradigm: Alternative Perspectives on Induction. Edited by Paolo C. Biondi and Louis F. Groarke, De Gruyter: 343-380.

Rasmussen, Douglas B. and Douglas J. Den Uyl. 1991. Liberty and Nature: An Aristotelian Defense of Liberal Order. LaSalle, IL: Open Court.

_____. 1997. Liberalism Defended. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

_____. Norms of Liberty: A Perfectionist Basis for Non-Perfectionist Politics. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

_____. 2020 The Realist Turn: Repositioning Liberalism. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave

Macmillan.

_____. 2023. Three Forms of Neo-Aristotelianism Ethical Naturalism: A Comparison. Reason

Papers. 43 (2)

Skoble, Aeon J. 2008. Reading Rasmussen and Den Uyl. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

_____. 2023. Aristotelianism and Neo-Aristotelianism. Reason Papers 43 (1).

Younkins, Edward W. 2021. Freedom and Flourishing: The Works of Rasmussen and Den Uyl.

Liberty (April 27).

_____. 2021. Rasmussen and Den Uyl’s Trilogy of Freedom and Flourishing. The Savvy Street

(Nov. 23).