Translating deep thinking into common sense

Talk About “Family Values”!

By Walter Donway

October 17, 2017

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

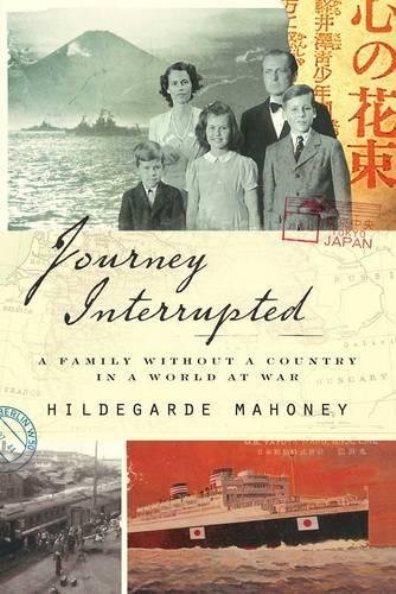

Journey Interrupted: A Family Without a Country in A World at War by Hildegarde Mahoney (Regan Arts: New York, 2016).

To evaluate a book fairly, the reviewer must assign it to a category (or categories) because each has somewhat different goals and standards. Dogs are assessed against “best of breed”-and so are books.

To evaluate a book fairly, the reviewer must assign it to a category (or categories) because each has somewhat different goals and standards. Dogs are assessed against “best of breed”-and so are books.

Less than halfway through Journey Interrupted, with Hillie Ercklentz and her family virtually interned in WWII Japan, starving in a mountain summer cottage in the frigid Japanese Alps, I knew unmistakably that this is inspiration. Her parents, Hildegard and Enno Ercklentz, so recently an affluent German couple in love with America, living in comfort on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, have dealt with what the author calls, with superb understatement, “interruption.” After a landslide of unpredictable setbacks, the parents, Hillie, and her older and younger brothers, are surmounting all obstacles, cooperating in the face of growing dangers, loyal to each other—but also still growing, learning, and, yes, even managing to be happy.

Journey Interrupted also must be reckoned both a classic account of what Leo Tolstoy called “a happy family” and a coming-of-age story focused on Hillie. Written consistently from her point of view, the book succeeds in all three categories—family, coming of age, and inspiration—because she rarely reports more than what she did, saw, heard, or felt. That stylistic discipline is amazing and effective. Caught in the rush of momentous events from Pearl Harbor to Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union to the atomic bombs to the Nuremberg tribunals—all directly impinging upon her family—the author’s concrete, evocative, and yet muscular style puts one family’s world before us so convincingly that we sense the whole world outside.

Journey Interrupted also must be reckoned both a classic account of what Leo Tolstoy called “a happy family” and a coming-of-age story focused on Hillie. Written consistently from her point of view, the book succeeds in all three categories—family, coming of age, and inspiration—because she rarely reports more than what she did, saw, heard, or felt. That stylistic discipline is amazing and effective. Caught in the rush of momentous events from Pearl Harbor to Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union to the atomic bombs to the Nuremberg tribunals—all directly impinging upon her family—the author’s concrete, evocative, and yet muscular style puts one family’s world before us so convincingly that we sense the whole world outside.

It begins in Manhattan on a May morning in 1941, Hillie’s last day of second grade at the Convent of the Sacred Heart on East 91st Street:

“At my age, I was mostly unaware of wider events. I was mainly concerned with the new braces on my teeth, which an orthodontist recently had put on, as well as keeping my hair under control after having had my first permanent…”

Thus, on one level, seven-year-old Hillie is just a little girl focused on a girl’s concerns, but from the first page her intuitions portend a world of drastic change, the unknown, the unimaginable. This is the day that her father will pick her up from school in a taxi that will take the family to Grand Central Station to board the legendary 20th Century Limited on the first leg of an epic journey. As an aside, those familiar with an earlier America will savor a chapter or two of nostalgia before catastrophe strikes because the family’s journey across America by train, their stay in the historic Mark Hopkins Hotel in San Francisco, and their departure on a luxury cruise ship for Japan are filled with snapshots of places, views, and the elegance available in an older America.

From our perspective, today, the trip planned by Hildegard and Enno for their family seems not challenging or “epic,” as it did to them, but a rash thrust into the whirlwind of war. Hillie’s father, head of the New York Office of the Commerz und Privatbank, headquartered in Berlin, has been called back to Germany because of the war. Germany is at war with Britain, but it is, so to speak, early times. The United States, the Soviet Union, and Japan have not entered the war. Her father’s aspiration from young manhood has been to work in New York City and that dream and motive will shape him for literally years as the family is marooned abroad.

Their plan is to avoid the treacherous Atlantic, where Germany and Britain are in a titanic struggle for supremacy, by traveling to San Francisco, Japan, China, and to board the famous trans-Siberian railroad to European Russia and thence to Germany. They have barely landed in Yokohama when rumors flare that the infamous Hitler-Stalin nonaggression pact has been thrown aside. Just days later, the Nazi armies launched an all-out predawn invasion of Russia.

With that single development, perhaps the least expected of the war until then, their journey becomes impossible: “interrupted.” It is here that we see, through Hillie’s eyes, how her parents will respond to successive body blows to their plans. At every wrenching turn, and almost despite other pressures and fears, there is a premium on experience, learning, growing. As weeks pass while Hillie’s father struggles to secure berths on a neutral ship returning to America, the family explores Japan from the grand (Mount Fugi) to the particular (a kimono and all accessories) that becomes Hillie’s brief obsession. These lighter moments, like the humorous interludes in Shakespeare’s grimmest tragedies, serve to increase uneasiness in the reader. Only we know what is coming.

As the summer passes and passage to America remains unavailable, the family settles in a house on a fashionable bluff over Yokohama and the children find schools. Of many foundations that permit this family some stability and continuity in a chaotic world, just one is their Roman Catholic faith. From New York to Yokohama to post-war Germany, the centuries-old worldwide commitment to Catholic schools becomes a firm support in one girl’s and family’s life.

The author recreates the daily reality of a family as it regroups, resettles, and pulls together for its values. The theme recurs again and again as the outside world darkens. The next blow is the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, igniting an instant, bitter state of war between Japan and America. Is there one ray of light in the darkness? The family is German and Germany promptly becomes a war ally of Japan. But at the same time, Germany and the United States declare war.

Hillie struggles to comprehend the consequences of each calamity for her family. Although they view themselves as American, and never stop doing so, they are German. To return to America is impossible. To reach Germany is impossible; indeed, had they left for their trip across the Soviet Union a week earlier, they would have been trapped in totalitarian communist Russia in its all-out war for survival with Germany. In Japan, at least, they are the nationals of an ally. How much will that protect them, for how long?

At no other juncture is Hillie’s father as thunderstruck, as confounded by fate’s timing of events:

“Come here and sit down with us. Something terrible occurred earlier today. It is unbelievable, but it happens to be true. This morning, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii…. incredible… a total surprise attack on Sunday morning, there. Apparently, they have destroyed most of the American fleet.”

The children ask their questions, trying to grasp what happened, what it means, and, above all, when they will return to America. “We’ll see” became her father’s constant mantra, says Hillie. No wonder!

Life for the family in Yokohama in the next few months reverts to the theme of resourcefulness. The author never exaggerates what befalls her family in comparison with the worldwide destruction and death that overtook millions of families. The German bank keeps paying her father a salary. What the family needs it can buy, assuming availability in wartime Japan; they are not unable to enjoy a new adventure. Indeed, her parents relentlessly insist upon it and the spirit moves the children.

And yet, the reader comes to understand that ability to find enjoyment is far from automatic. It is an achievement. Family life, little festivities, some excursions, and new friendships occur because Hillie’s parents insist that they occur in spite of everything. For example, Enno soon is summoned to the office of the local representative of the German Gestapo, who demands that he switch the children out of Catholic schools. (Not on the Nazi-friendly list.) And, also, why doesn’t Enno join the Nazi Party? Enno refuses both. Before long, it becomes clear that the Japanese internal security agencies, too, are spying on foreign nationals. Whole families disappear for seemingly slight provocations. A child as young as Hillie’s brother, Alexander, must be made to understand that any word, any gesture, could bring troubles cascading into disaster. It is in the face of this growing fear that the flexibility, maturity, and resourcefulness of her parents maintain a sense of the normal in Hillie’s world, a sense that childhood is to be enjoyed.

When American air attacks soon reach Japan’s shores, and warships inexplicably sink in Yokohama harbor, the Japanese insecurity and anger become palpable—and active. Foreign nationals are forced out of Yokohama. Struggle, settlement, and disruption continue as the war becomes more desperate until the family and some thousand other foreign nationals are exiled to a summer resort village high in the Japanese Alps. In a cottage in Karuizawa, at the foot of the mountains, their most severe trial begins, with rations diminishing, travel forbidden, only wood stoves for cooking and heat, and both Japanese and German spies on the job. Hillie and her family endure a long winter during which starvation haunts the town and every improvisation and diligence is required even to obtain fresh water:

“…a handful of rice per person per day, soybean paste—with which our parents had learned to make miso soup—a loaf of bread per week for a family of five…. My father had learned to cut a loaf of bread into thirty-five prosciutto-thin slices so we would each have one slice per day…”

For all that, the author’s evocation of the sights, tastes, and sounds of every experience gives the days of spring and summer their due in a rural Japan still scarcely modern. Her parents again manage to create a world of schools, pets, and holidays, and create a constant sense of expectation, performance, and duty that mature Hillie into a charming, graceful, and immensely able woman—and formidable homemaker.

Neuroscientists like Harvard Professor Stephen Pinker view the effects of birth order as a valid study of how pressure for survival has shaped behavior. In Hillie’s family, the eldest child was Enno, named after his father, three years older than Hillie and thus the classic “first lieutenant” striving to rise to his father’s standards. As the only girl, Hillie, in a family with strict standards, would strive to meet her mother’s expectations, including care for the “baby,” Alexander, four years younger than Hillie. As youngest in an intensely striving family, Alexander could be expected to be precocious and, perhaps, most politically liberal. It is all great fun, but there is at least some evidence in Journey Interrupted for these speculations. The larger point is that all three, exposed to instability, abruptly changing circumstances, and considerable anxiety, appear to have excelled in all the expected ways. And that, surely, is a tribute to family values.

Virtually cut off from the world, except for an illegal and potentially dangerous shortwave radio (the children stand sentry outside while Enno seeks a fragment of English-language news), the family hears only along with the assembled villagers the Emperor’s historic broadcast explaining that the atomic blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki (referred to only vaguely) have persuaded Japan to sue for peace.

I find myself uneasy skipping parts of the book, as I must, because suspense keeps mounting as each seeming triumph over difficulties is met with a door opening onto another struggle. The American military occupation of Japan, coming in the spring, is almost like a celebration and party—food, friends, and security—but not without its scary risks for nubile young women like Hillie. General Douglas MacArthur, who came to be revered by Japanese and Americans alike–decided that all nationals stranded in Japan during the war must be repatriated to their home countries. It means for Hillie’s family no trip “home” to America, but instead a troop ship to devastated, starving, bombed-out post-war Germany.

Make the best of it. That simple theme deepens as Journey Interrupted continues. Both Hillie’s parents have family in Germany—indeed, deep roots in the area of Stuttgart and elsewhere. A torment during the war had been a total absence of news from Germany at a time when Hildegard and Enno knew unimaginable chaotic dangers touched everyone. When news at last arrived, it was that Enno’s youngest sister and youngest brother both had been killed in the war. Other family had fled their homes in advance of the universally dreaded murderous brutality of the Red Army.

To travel to Germany was at once a prospect of reunion with cherished surviving family in the ashes of Germany and another postponement of return home. It also meant arriving in Ludwigsburg, near Stuttgart, to be interned in a barbed-wire enclosed prison camp for men and women alike and “de-Nazified.”

Journey Interrupted follows the family in Germany for some two years stretching from the defeat of Japan to the beginning of the German “miracle” of economic recovery, the Berlin airlift, and the conclusion of the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals. For Hillie, though, it is her teenaged years of becoming a young woman, by all accounts beautiful, discovering talents in singing and acting, and falling in love.

Journey Interrupted follows the family in Germany for some two years stretching from the defeat of Japan to the beginning of the German “miracle” of economic recovery, the Berlin airlift, and the conclusion of the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals. For Hillie, though, it is her teenaged years of becoming a young woman, by all accounts beautiful, discovering talents in singing and acting, and falling in love. Again, schools are at the core of her experience, but in addition a marvelous extended German family—all grateful to have survived the war, all struggling to eat in famished Germany, to invite back life.

“Family values” do rear their head as regularly as ever, when Hillie goes off deliriously excited for a long weekend at the home of a boy from school.

“My father…took me aside and told me in no uncertain terms that nothing was to happen that could lead to my becoming pregnant—and that if it did happen, I should forget about ever coming home again.”

(As an American college boy of the 1960’s, I would have viewed this as little short of a manifestation of fascism. Today, I am not at all as sure!)

At times, the life seems idyllic, but that is because Hillie’s family (and relatives, it seems) were endowed with “German” virtues such as self-reliance, hard work, cooperation, loyalty to family, and duty. Thus, living at the country hunting lodge of her grandparents in Wentorf, near Hamburg (commandeered as living space for three or four refugee families, as well), Hillie savors fresh venison, mushroom soup, fresh vegetables, and orchard fruits—because that was what could be foraged from the countryside and forage they did.

And then, when she was all-too-well settled in school, in love, impassioned about performing in operas, Hillie’s “homecoming” materialized, at last, with permission for the family to return to America. In bed that night, she wept for hours, barely consoled by her grandmother.

Such moments of succumbing to pain, though, are mere intervals for the family. One is always ready to comfort and support another. Day dawns, Hillie takes stock, and sets out on the next adventure.

Returning to New York brought the joy of old friends, the friendly neighborhood, but also the last of her father’s income and savings. After many years out of work and his profession—and as a German after the bitterest of wars—her father struggled for employment. By now thoroughly schooled in thinking in terms of family, Hillie set aside the question of college and went to work as an office girl at Time, Inc.

In New York, a woman of her beauty, maturity, and sheer spirit of excitement could not long escape notice. She was drawn into modeling and soon had won perhaps the world’s most competitive modeling-advertising contract as Miss Reinhold for 1956. At the same time, she met and married Arthur Merrill (of Merrill, Lynch), and had her first child.

A girl’s trajectory through life had been interrupted in the most total and unforgiving manner—as though the world conspired to stop her—and, now, she has resumed that journey with incomparable momentum and promise.

Here, the author concludes Journey Interrupted, and the logic is unassailable. A girl’s trajectory through life had been interrupted in the most total and unforgiving manner—as though the world conspired to stop her—and, now, she has resumed that journey with incomparable momentum and promise.

Indeed, the entire family, as she recounts in the postscript, were back on track with her brothers in prestigious universities, her father in a new career, and her mother as always anchoring life for the whole family.

The year is 1956 in a decade many Americans recall as America’s own returning to its interrupted journey after depression and war.

Hillie is home.