Translating deep thinking into common sense

The Fountainhead of Irrationality in the West

By Vinay Kolhatkar

August 19, 2018

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

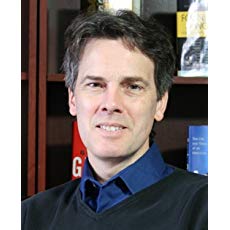

Stephen Hicks is Professor of Philosophy at Rockford University, Illinois, where he also directs the Center for Ethics and Entrepreneurship. He is the author of two books in intellectual history: Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault and Nietzsche and the Nazis. His other publications include essays and reviews on education, entrepreneurship, and ethics in publications such as Review of Metaphysics, Business Ethics Quarterly, and The Wall Street Journal. He blogs at StephenHicks.org.

Stephen Hicks is Professor of Philosophy at Rockford University, Illinois, where he also directs the Center for Ethics and Entrepreneurship. He is the author of two books in intellectual history: Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault and Nietzsche and the Nazis. His other publications include essays and reviews on education, entrepreneurship, and ethics in publications such as Review of Metaphysics, Business Ethics Quarterly, and The Wall Street Journal. He blogs at StephenHicks.org.

In his book on Postmodernism, Prof. Hicks presents this summary of the contrast between the philosophy that has shaped the Western world since the Enlightenment and the alternatives to it demanded by postmodernism:

“Postmodernism rejects the Enlightenment—in the most fundamental way possible—by attacking its essential philosophical themes. Postmodernism rejects the reason and the individualism that the entire Enlightenment world depends upon. And so it ends up attacking all of the consequences of the Enlightenment philosophy, from capitalism and liberal forms of government to science and technology.

“Postmodernism rejects the Enlightenment—in the most fundamental way possible—by attacking its essential philosophical themes. Postmodernism rejects the reason and the individualism that the entire Enlightenment world depends upon. And so it ends up attacking all of the consequences of the Enlightenment philosophy, from capitalism and liberal forms of government to science and technology.

“Postmodernism’s essentials are the opposite of modernism’s. Instead of natural reality—anti-realism. Instead of experience and reason—linguistic social subjectivism. Instead of individual identity and autonomy—various race, sex, and class groupisms. Instead of human interests as fundamentally harmonious and tending toward mutually-beneficial interaction—conflict and oppression. Instead of valuing individualism in values, markets, and politics—calls for communalism, solidarity, and egalitarian restraints. Instead of prizing the achievements of science and technology—suspicion tending toward outright hostility.

“That comprehensive philosophical opposition informs the more specific postmodern themes in the various academic and cultural debates.”

Professor Hicks (SH) kindly agreed to a wide-ranging interview with Savvy Street’s Vinay Kolhatkar (VK) on a core source of irrationality, the philosophical package broadly termed as Postmodernism, and its serious aftereffects on modern society.

VK: When were you first exposed to Postmodernism?

SH: The elements of Postmodernism have been part of philosophy since the ancient Sophists, so I encountered them all through my education. But I became aware of them as an integrated package and movement in the mid-1990s, in the years after finishing grad school and reading more widely.

VK: In your book Explaining Postmodernism: Skepticism and Socialism from Rousseau to Foucault, you say that all intellectual movements are followed by a backlash, a counter-movement. Why is that?

SH: That’s been the historical pattern. Part of it is that theories are complicated and it’s hard to get everything right. Any theory’s weaknesses are teased out by intellectuals. That’s part of their job. Those weaknesses then provide counter-attack opportunities to the theory’s enemies. Part of it also is that successful theories seem always to lead their adherents to rest on their laurels, and that also provides opportunities for underdog theories and their adherents.

VK: Where then is the populist backlash against Postmodernism? How long will we need to wait for it?

SH: That’s unpredictable. But as many of the pathologies of Postmodernism become obvious and spill out into popular culture, concerned and thoughtful individuals educate themselves about it and start fighting back. It’s early stages now, but I sensed a significant increase in popular awareness of postmodernism in 2015, when many nasty campus events made it into the mass media.

VK: “Notwithstanding that Marxism is a four-letter word in the U.S., multitudes, including many that are highly educated or clever, have unwittingly accepted several Marxist principles into their subconscious.” Would you agree? If yes, why? If no, why?

SH: Marxism has mutated successfully in intellectual life because it has attracted many clever individuals. Why were so many clever individuals attracted to it? In part because it offers a simple-to-grasp theory that initially seems to explain much. In part because it taps into anti-money, anti-business, anti-wealth, and anti-individualistic attitudes that are longstanding parts of our culture.

VK: Is it envy alone that fuels the great attraction to Marxist principles and its successors in Postmodern philosophy? Or is there a deeper cause?

SH: It’s not envy alone—there are other psychological factors such as guilt or laziness or self-doubt or ‘quick-fixism’ or power-lust that can predispose one to it. At the same time, Marxism is a theory that does have some arguably reasonable premises and some apparent explanatory power, so the attraction can be primarily intellectual. Yet ascribing any set of causes to any given individual requires getting to know that individual well. Any longstanding movement has individuals in it who got there by different intellectual and more broadly psychological routes.

VK: How would you link neo-Marxists (thinkers influenced by Karl Marx) with postmodernists?

Marxism’s weaknesses led its followers to tweak and modify the system endlessly for 100 years, until a subset of them in the mid-20th Century kept the normative core of Marxism but abandoned its metaphysics and epistemology and substituted Nietzsche’s and Freud’s.

SH: That took me 50-something pages to do in Explaining Postmodernism, and that was to focus only on the politics and economics. The short story is that Marxism’s weaknesses led its followers to tweak and modify the system endlessly for 100 years, until a subset of them in the mid-20th Century kept the normative core of Marxism but abandoned its metaphysics and epistemology and substituted Nietzsche’s and Freud’s.

VK: Is there a multi-disciplinary, international association of academics against Postmodernism? If not, would it be a good idea to form one with alliances with the sort of media that is uncorrupted enough to give them a voice?

SH: Yes to the first question. Heterodox Academy is active and doing good work, and it has a strong chance of success because it is well strategized intellectually and its membership spans most of the political spectrum. The National Association of Scholars has also been active for several decades now, fighting for the principles of genuine liberal education. And before them, the American Association of University Professors has long been an advocate for professors’ rights to academic freedom, informed by broadly healthy principles.

VK: What can the citizen not in a position of power do about this postmodernist assault on Western civilization?

SH: Three thoughts here. One is that Postmodernism is an assault on Western civilization in particular, but it’s more important to recognize that it’s an assault on civilization generally. The principles that make human flourishing most possible happened to have been best articulated in the West, but “Western” civilization is becoming a misnomer as the principles have gone global.

Postmodernism also came out of Western civilization. One can argue that it’s an internal cancer, but it’s not an import from an alien culture.

A second thought is that Postmodernism also came out of Western civilization. One can argue that it’s an internal cancer, but it’s not an import from an alien culture.

The third thought is that every citizen is in a position of power. Barring outright slavery and various degrees of government imposition, each of us individually is in control of our lives. So let’s not let postmodernist cynicism and adversarialism into our souls. Also, most of us live in amazingly rich places, by historical standards. So there’s a lot of power available to everyone to make a good life. If, in addition to that, one wants to become a social influencer, the power-potential is there as well. Media access is cheap, and other people are attracted to those who seem to have their lives together and have a good product or message.

VK: Postmodernism has invaded economics, philosophy, culture, art, psychology, medicine, climate science, journalism, politics, physics … the list is endless. Is there a “safe space,” that is or will not be under attack?

SH: No. Inside the university, every field is both an opportunity for research and progress—and a battleground. New ideas will always be contested, and all the old debates will likely carry on for generations. And that’s mostly what universities are for.

The same is true outside the universities, in the broader intellectual culture. Postmodernism is a major part of the mix now, and as a philosophy its principles have universal application to all issues. So doing creative work—and having to fight for the principles that make creative work possible—that’s part of everyone’s life.

VK: If a young person with flawless integrity considering a career in academe in philosophy or the humanities approached you for advice, what would you say?

Philosophy is in better shape than many of the other disciplines, and there are still plenty of healthy individual professors and departments.

SH: Philosophy is in better shape than many of the other disciplines, and there are still plenty of healthy individual professors and departments. So if you’re passionate about an academic career, first do your research to find the healthy people and places. Then go for it. Exercise prudence about whom you argue with and how, and choose your mentors and allies wisely. But don’t let the unhealthy stop you from choosing your first-choice profession.

VK: Many thanks for your time, Stephen. We wish you the very best in your endeavors to reach an ever-widening audience with your work.