Translating deep thinking into common sense

The Joyful Feminism of Wonder Woman

By Jason R Walker

June 28, 2017

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

The best adaptations require quality source material. Wonder Woman, like Superman and Batman, is a romantic hero in a world of darkness and cynicism, with an indefatigable sense of the good and the right as her most powerful weapon.

After so many years of box office hits, it would be natural to wonder if there are any major comic book icons left who haven’t gotten the big screen, big budget treatment. The Marvel universe already seems about tapped out; if their properties haven’t already been big budget films, complete with multiple sequels and reboots, they’ve been series on Netflix or traditional television. Their counterparts at DC have had more mixed luck. Though the era of modern comic book film franchises had their start with DC adaptations like Richard Donner’s Superman (1978) and Tim Burton’s Batman (1989), other attempts, like Green Lantern, have won less favor with fans. The more recent Man of Steel and Batman v. Superman were relative successes, but not without controversy. The “Arrowverse” television series demonstrated that some of the lesser known DC properties, like the eponymous Green Arrow, Flash, Supergirl, and Legends of Tomorrow, have live-action viability. It’s in that context that the only DC property of comparative stature with Batman and Superman, Wonder Woman, after decades of failed attempts at big budget films and television series, finally has her own film.

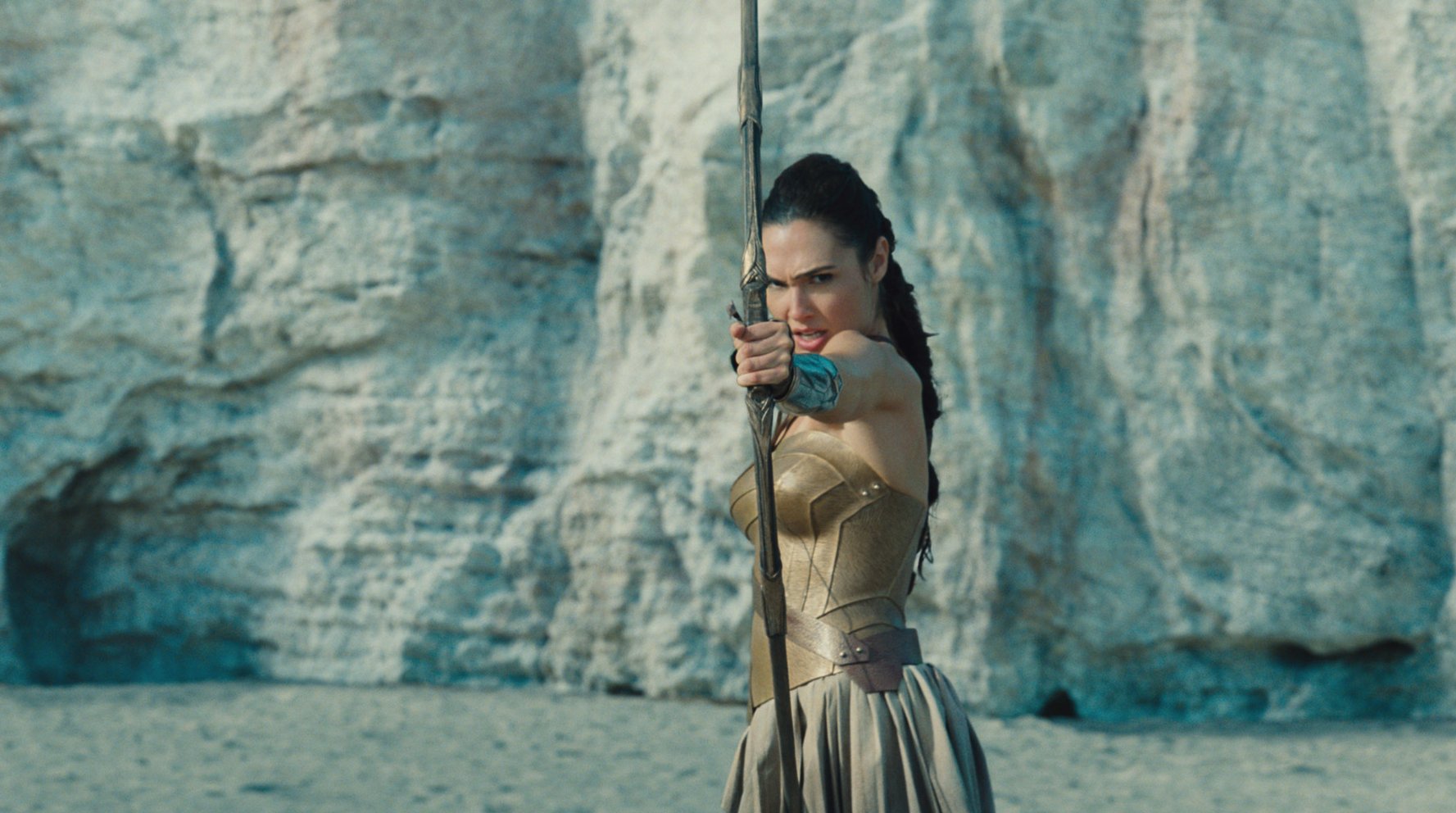

Wonder Woman is hardly a new creation; she was originally introduced to comic book readers not long after Superman and Batman, debuting in 1941. She was created by William Moulton Marston, a psychologist and writer perhaps equally well-known for his invention of the polygraph. (It can scarcely be a coincidence that among Wonder Woman’s gifts as a hero is a magic lasso, compelling those captured by it to divulge the truth.) Although consistently appearing in comics since 1941, and prominent in animated media, her history in live-action media is spottier. Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman was originally introduced to movie-goers in Batman v. Superman, and, interestingly, her character was the least controversial and most universally lauded aspect of that film. But prior to Gal Gadot, we have only the campy 1970’s Lynda Carter television series, better experienced through the rose-colored glasses of nostalgia than directly in reruns. Why the lack of attention in live action filmmaking, relative to Batman and Superman? Many would argue sexism against female heroes, but I favor a simpler explanation: Wonder Woman is just a harder character to do well. Were it simply sexism, Warner Brothers wouldn’t have poured so many millions in so many different Wonder Woman film and television projects, including as recently as 2011 with a failed television pilot, before finally getting it right with Patty Jenkins. And by “getting it right,” I mean on par with the cinematic classics of Donner’s Superman and Burton’s Batman. Warner could afford to bungle Green Lantern, but not so with a cultural giant like Wonder Woman.

Where Batman’s powers are technological and psychological, and Superman’s powers result from an alien physiology, Wonder Woman is literally a Greek demigod.

Of course, the best adaptations require quality source material. Wonder Woman, like Superman and Batman, is a romantic hero in a world of darkness and cynicism, with an indefatigable sense of the good and the right as her most powerful weapon. Where Batman’s powers are technological and psychological, and Superman’s powers result from an alien physiology, Wonder Woman is literally a Greek demigod, the daughter of Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons, and Zeus. Raised among the all-female Amazons, Diana knows only the Greek-influenced world of the island paradise of Themyscira, before rescuing the American spy Steve Trevor from a plane that crashed there. Trevor is the first man to set foot on the hidden island, and his arrival forces the Amazons to reconsider their isolation from “man’s world,” given the possible return of Ares, the god of war. Disobeying her mother, Diana volunteers to return Trevor to his world, and to defeat Ares, as she believes him to be the instigator and mastermind behind the Great War engulfing the world.

The film departs from the “prime” DC Comics universe in a few ways. In the comics, Diana’s rescue of Trevor and introduction to the world beyond Themyscira—is set in contemporary times. Trevor is an American special-forces operative, rather than, as in the film, an American working for British intelligence during World War I. Some versions of the story of her origin have the design of her battle uniform chosen explicitly as a mash-up of her Amazonian roots and to honor both Trevor’s national affiliation and her own chosen home of the United States, but there’s no other indication in the film of any American affiliation for Diana, who seems more cosmopolitan in orientation in it. The name, “Wonder Woman,” is never used in any line of dialogue; she is only known by her given name, Diana, Princess of Themyscira, or her hastily chosen civilian alias, Diana Prince, whereas in the comics, “Wonder Woman” , as with “Superman,” comes from the press and is adopted, albeit reluctantly. But as with the comics, the film’s version of Trevor serves as a kind of male counterpart of Lois Lane—both a romantic interest and a representative of humanity, helping Diana navigate an alien world. Those “fish out of water” elements, as Diana builds a rapport with Trevor, provide the primary source of the film’s moments of levity.

Contrary to the expectations of many, the political correctness of recent films is notably toned down in this iteration. There are nods toward the plagues of racism and sexism, but the World War I era setting contextualizes them considerably as maladies of the past rather than, for example, the reason for Hillary Clinton’s failure to get elected.

Contrary to the expectations of many, the political correctness of recent films is notably toned down in this iteration. There are nods toward the plagues of racism and sexism, but the World War I era setting contextualizes them considerably as maladies of the past rather than, for example, the reason for Hillary Clinton’s failure to get elected. Diana reacts to misogyny in a more bemused manner than with a sense of victimhood. One recalls Atlas Shrugged’s Dagny’s retort: “The question is not who will allow me; the question is, who will stop me?”—a sentiment very much in line with Wonder Woman’s own sense of life.

Thematically, the film seemingly functions as an anti-war film. After all, Ares is the chief villain, and Diana’s primary motivation to leave Themyscira is to stop the war’s senseless bloodshed, given the premise that this is a “war to end all wars.” At first glance, it might seem like the film embraces a “peace at any cost” ethos, but the narrative then subverts that idea by having those very words spoken by a villain, who sees an impossible-to-keep Armistice as a good outcome by his lights, since that makes a future war more likely. Complicating further that simplistic take is also the paradox that Diana, as an Amazonian warrior, wages a kind of private war herself, if only as a means to make the “war to end all wars” the real outcome. Indeed, the conceit that World War I could ever have had that outcome, however earnestly believed by any character, is a red flag to audiences in 2017 that the character is more likely than not to be in for a rude awakening. A possible inconsistency here is that Ares seems at cross purposes, seeking both a doomed Armistice and an enhanced German chemical weapon, designed to extend the war and give the Germans of 1918 a fighting chance at victory. But we gradually learn that Ares is only indirectly responsible for the war, and whether he achieves a prolonged conflict or an unjust armistice, his ends are served either way.

Diana begins her odyssey into the “world of man” with a certain naivety; Steve Trevor frequently has to correct her under informed conceptions of the war and the cultural forces fueling it. In contrast to the Christian notion of original sin, she sees humanity as essentially good, but for the corruption introduced by Ares, a literally fallen god sharing as many similarities with the Christian legend of Satan as with the original Greek war deity. However, she gradually comes to understand that humanity’s moral agency implies that they sometimes make bad choices. Ares, under Diana’s lasso of truth, denies responsibility for the war, blaming humanity itself.

In a perverse way, Ares claims to seek peace: the peace of the tomb, of mankind’s ultimate destruction. Showing Diana a vision of Earth turned into a lush garden, contrasting with the destruction brought by the war, he offers her a kind of last temptation of Christ: join him to help end humanity to make this paradisiacal Earth a reality. Rather than directly face Ares’s question of whether humanity in some sense deserves to survive or is worthy of her protection, Diana challenges the premise that it is a question of collective merit or justice at all, instead reframing the question in terms of humanity’s moral aspiration. This is fine as far as it goes, though I found myself wishing that Diana responded with some variation of Nietzsche’s argument that questioning the value of living suggests a neurosis, since it is life itself that gives meaning to value. Indeed, the very hubris of both questions should have been directly challenged. Either is ultimately a collective moral judgment of a kind, and surely it matters far more what each individual does or aspires to, than the group she is a part of. And individuals, in the absence of knowledge (a state which Diana frequently possesses), ought to be entitled to a presumption of innocence. This doesn’t mean she still has a duty to sacrifice for the collective, but it does mean that she is right to use her powers to protect them if she finds meaning in doing so. And this she clearly does. She is in her self-actualizing element when she battles evil, and the film shows us that even as a child, she enjoys the training Amazons undertake to be skilled warriors. In battle, her face typically displays a look of grim resolve, but it’s not hard to pick up on the subtle grins and even joy she experiences when battle comes her way.

This is not to suggest that Diana lives only to fight; she finds more than enough to fight for, in her appreciation of humanity in general and her love of Steve Trevor in particular, to name a few. And it’s often in those tiny moments, when she at first mocks a style of dancing as mere swaying, only to find, after trying it herself, to be swept up in its charm, that this appreciation comes out. In Milton’s Paradise Lost, we see one of the first moments of cultural modernity, when Adam and Eve, expelled from the Garden of Eden, are told by the Angel Michael that they may find a more profound happiness outside Paradise. Departing Paradise, rather than a tragic event to bemoan, becomes something to celebrate, as humanity gains its moral agency and self-awareness, however fallible that makes us. Diana’s own narrative arc parallels this nicely. The Amazons may have technically superior dances in Themyscira, but Diana comes to prefer the joyful, romantic dancing of a liberated people in a Belgian village.

But that it works as well with a heroine, and offers a vision of a heroine finding no contradiction between, and embodies in equal measure strength, justice, tenderness, and femininity, implies a feminist statement of the best kind. No ideological didacticism is necessary: Wonder Woman, as a character, is her own feminist statement.

Though I don’t take the film to intentionally be a feminist statement, in its own way, it offers one. A version of this basic narrative, starring a male demigod encountering and defending the modern world, could have been possible. (Arguably, this is what we have in Thor.) But that it works as well with a heroine, and offers a vision of a heroine finding no contradiction between, and embodies in equal measure strength, justice, tenderness, and femininity, implies a feminist statement of the best kind. No ideological didacticism is necessary: Wonder Woman, as a character, is her own feminist statement.

The film, ultimately, serves its task as an introduction to this pop culture icon. But of course, even the best introduction can only do so much. The ongoing Wonder Woman comic book series provides a much deeper and compelling narrative of a hero who has perhaps the best sense of life in the romantic sense. The Wonder Woman of the comics, like that of the film, captures a playful joy in living and being one’s best self, combined with a profound, unflinching sense of justice. Though the ancient Greek culture that inspired Wonder Woman as a character wasn’t known for its sexual equality or personal freedoms, it did give us an inspirational vision of heroism, which we now find embodied in characters like Wonder Woman.