Translating deep thinking into common sense

The Most Overrated Novel Everybody Has Read

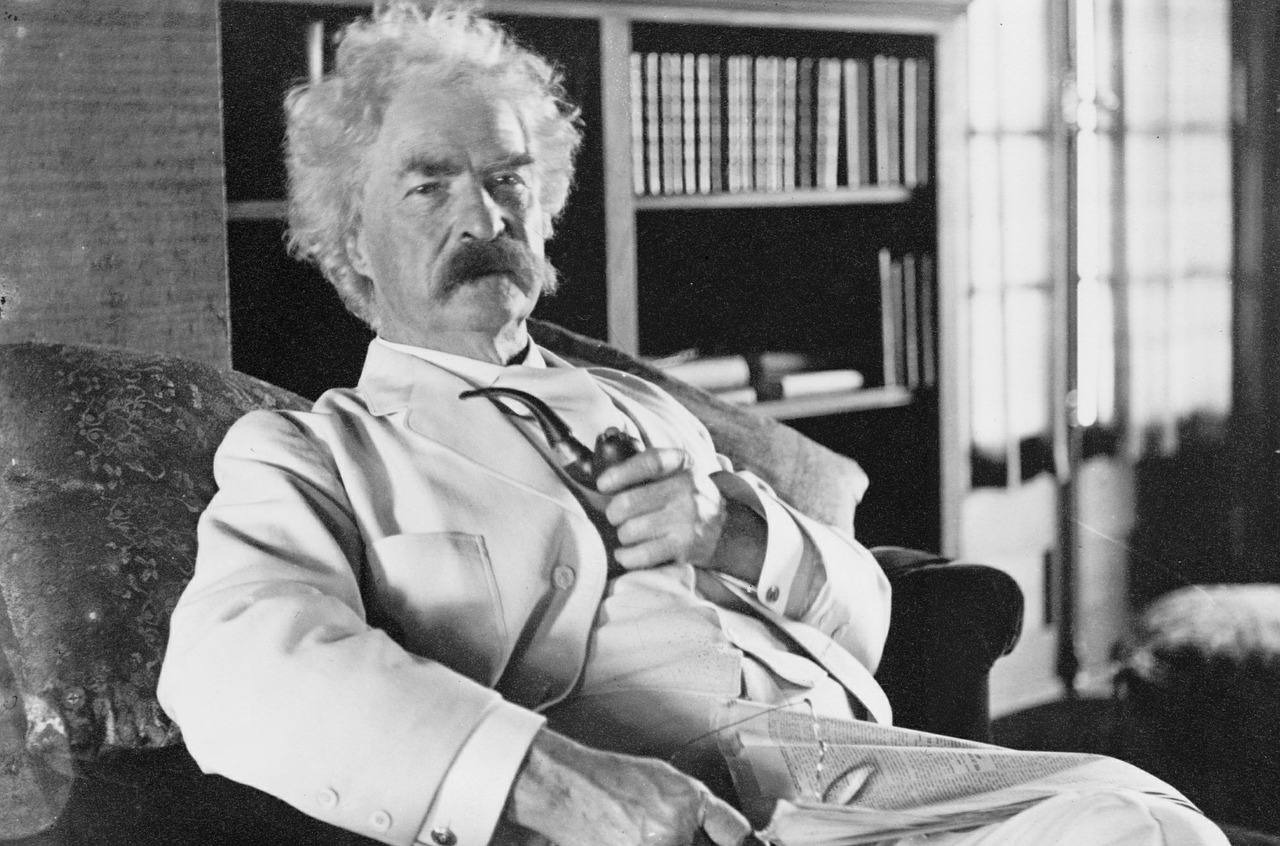

By Robert Gore

October 2, 2014

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is not a bad novel, it is just not a great one. It is not even the best novel Mark Twain wrote about boys growing up on the Mississippi River; that honor goes to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Yet, Huckleberry Finn has been widely hailed as The Great American Novel, praised by, among others, T.S. Eliot, F. Scott Fitzgerald, H. L. Mencken, and Ernest Hemingway, who famously said, “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called ‘Huckleberry Finn.’” It was standard assigned reading for generations of students, until the politically correct crowd banned it on racial grounds. Twain’s tale lacks the polemic power of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. However, Huck’s loyalty to his friend, Jim, and his attempt to help him escape slavery surely represent some progress for the notion of racial equality at a time―1885―when that idea was not generally accepted.

The first sentence of Huckleberry Finn: “You don’t know about me, without you have read a book by the name of ‘The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,’ but that ain’t no matter….” should give the modern reader pause. Hard experience instructs that subsequent iterations of dramatic works, like the progeny of those who accomplish great deeds, seldom live up to their progenitors. Huckleberry Finn is a sequel to Tom Sawyer, and as is usually the case, the author put most of his best work in the first book.

Two other aspects of that first sentence also instill misgivings. Unlike Tom Sawyer, Huckleberry Finn is written in the first person, and that first person is Huckleberry Finn. By choosing the most limited point of view, Twain is writing with one hand tied behind his back. Part of the joy of Tom Sawyer came from the author’s interjections, ranging from the occasional pithy zinger: “The less there is to justify a traditional custom, the harder it is to get rid of it,” to more extended displays of world-wise wit:

The writer of that passage was at times a great and wise philosopher, but in Huckleberry Finn, he must take all that greatness and wisdom and put them in a barely literate youth who has only mastered the multiplication tables up to six times seven equals thirty-five. The notion that Huck could write a book strains credulity past the breaking point. If Twain had gone first person in Tom Sawyer he would have at least had a more imaginative, intelligent narrator than he does in Huckleberry Finn, although he still would have been hamstrung by the inherent limitation of that point of view.

Many of the encomiums heaped on Huckleberry Finn reflect stylistic predilections or ideological bent. Perhaps no sin is more damning in modern literary criticism than for the reader, reading a book by an author, to detect that author’s views on anything, unless wrapped in obscurity so dense the reader is not even sure he or she has detected a view. Hiding the author behind a character’s point of view is mandatory. A direct statement is strictly verboten, an express ticket to critical hell, without a shot at a redemptive stay in literary purgatory. Avoiding perdition, Twain stays tucked safely behind Huck.

Huckleberry Finn embodies another of today’s cherished artistic totems: the enshrinement of the common man, or in this case, the common youth. Here ideology comes in; this idolatry can be traced back to Marx. The labor theory of value and “Workers of the world, unite!” have been transmuted to the art world, where an elite that wouldn’t be caught dead in a factory, slum, or workingman’s bar has erected a pedestal for art that wells up from “the common folk,” both as artists and subjects.

By that aesthetic, art from the defunct USSR should be a treasure trove, but it is mostly poorly-done posters, statues, poems, and stories—tributes to toilers for the common good. It is oxymoronic, expecting the uncommon from the common. Michelangelo was not a farmer; Shakespeare was not a stablehand. That is not to say that we do not get some memorable passages from Huck.

This is vintage Twain homespun humor, but it is infrequent, compared to Tom Sawyer, and much of it comes at the expense of Huck or Jim.

The author gives “Notice” at the beginning of the book that: “Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted, attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.” Here Twain can be taken at his word; not that these absences are considered defects in modern literary criticism.

Like the setting, the Mississippi River, the story flows and meanders; there is no discernible structure. Any mood-setting, nature-worshipping modern writer worth his or her salt can write paragraphs of prose bordering on poetry evoking the mystery, beauty, and wonder of the “Father of Waters,” but as anybody who has ever stood on a bank for any length of time can attest, its wide, flat, muddy expanse is pretty boring unless you’ve cast hook and line, and if the fish aren’t biting, that’s dull, too. The Mississippi is a carnival midway that Twain must fill with amusements and attractions.

When a movie or television show is advertised as “zany,” “madcap,” or “antic,” that’s usually a tip-off that it will not be very funny, its humor will be of the slapstick variety. Unfortunately, a publicist working on Huckleberry Finn would be stuck with those adjectives for significant chunks of the novel. Long before they make their final exit—tarred, feathered, and ridden out of town on a rail—the charlatans “king” and “duke” and their schemes grow tiresome. Annoyingly, until that exit, like the indestructible killer in a low-grade horror flick, every time you think they are gone, they reappear. However, their scheme to impersonate two brothers who are heirs to a substantial fortune offers Huck an opportunity to exercise his conscience. At the risk of being “banished,” here is the “moral” of the novel, such as it is: “Right is right, and wrong is wrong, and a body ain’t got no business doing wrong when he ain’t ignorant and knows better.”

There is another Mark Twain of whom most readers are unaware. “The War Prayer,” a harsh, scathing anti-war story, reveals a Twain far different from the repackager of Biblical platitudes. Twain could not get it published in 1904 or 1905, when it is believed written; it was published posthumously. This is a Twain stripped of any illusions about human nature, no humor to cushion his blow. That Twain puts in an appearance in Huckleberry Finn. A Colonel Sherburn shoots a man dead in the street and the citizens of the small town come to his house to lynch him. Sherburn confronts them:

The mob slinks away. Like “The War Prayer,” this scene disparages the common man and makes a powerful statement about crowd bravado and hypocrisy. The pieces open a window on Twain’s soul―what he really thought about people―a window he probably knew he had to keep shuttered if he wanted to sell many books.

Even Huckleberry Finn champion Hemingway advised readers to, “…stop where the Nigger Jim is stolen from the boys. That is the real end. The rest is cheating.” That “cheating” is almost a quarter of the book, and if it had been omitted, it would have left the novel about the same length as Tom Sawyer. Brevity is indeed the soul of wit. Twain imports Tom for this last section, and it is just what a book doctor, akin to today’s script doctors, would have ordered―bring in the stronger, more compelling character to juice up the ending. Unfortunately, Tom’s “rescue” of Jim has none of the earlier novel’s charm: getting other boys to paint the fence; horse trading tickets to get a Bible; a false but “noble” admission that he, not Becky Thatcher, tore the anatomy book. The rescue is absurdly cruel and tediously convoluted. Tom knows it is unnecessary and Huck plays along. They would not have done it if Jim had not been black and a slave, an “inferior.” So much for racial equality.

This is not the Tom Sawyer of the first novel, the Tom who, after his own crisis of conscience, at great personal risk reveals that Injun Joe, rather than the drunk, Muff Potter, murdered Dr. Robinson. One suspects that Tom Sawyer would rise in critical estimation if Potter had been the murderer and Native American Joe the falsely accused. Be that as it may, the murder and its aftermath give Tom Sawyer what is missing from Huckleberry Finn: structure, plot, and most importantly, continuing tension. In the latter novel there is the ever present threat of Jim’s capture, but it pales in comparison to the ever present danger faced by Tom after his courtroom revelation and Injun Joe’s escape. While both novels have happy endings, Huckleberry Finn’s stems from a contrived series of coincidences and can, as Hemingway noted, be safely skipped, while Tom Sawyer’s comes only after a harrowing ordeal in a cave with Becky Thatcher and the death of Injun Joe. Tom deserves to get his money and his girl, and readers deserves their happy ending.

It is worthwhile reading virtually anything by a writer of Mark Twain’s caliber; certainly more rewarding than staring at the television, a trip to the movie theatre, or reading this month’s bestseller. Huckleberry Finn should be read and reread, but Tom Sawyer should be read and reread first; that is its proper place, both chronologically and in literary merit.