Translating deep thinking into common sense

The Neuroscience of Cringe: Why the Past Still Burns

By Walter Donway

April 6, 2025

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Nowadays, it is called “cringe,” that half-embarrassed, half-repulsed feeling that makes us squirm—face-palm, flush, talk (maybe shout) aloud, clench the steering wheel—at a memory from a time, a place, that has no business in our minds. Except, it turns out that it does.

The time I mispronounced a word, which of course had to be “clitoris” and had to be in a dorm bull session of worldly-wise freshmen of both sexes. That time I confidently whispered to my drinking buddy a “dirty” joke and he guffawed: “Walter! I could tell that one to my grandmother!” That dressing down by my boss, Margaret, eons ago around a table with the whole staff—all those quick, sidelong glances of pity.

The scientific term is “involuntary memory” or “intrusive memory.”

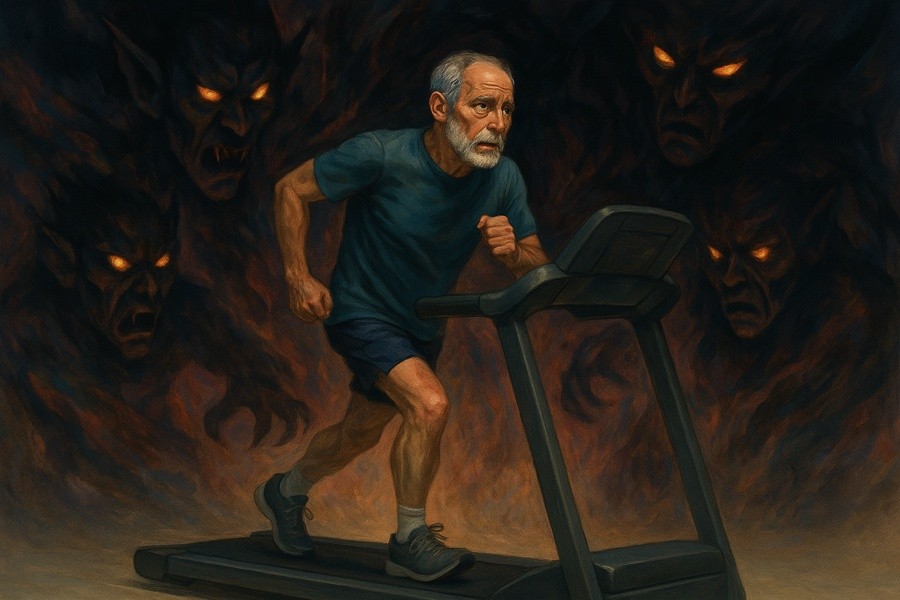

The scientific term is “involuntary memory” or “intrusive memory.” My brother and I always called these remembered moments “petty indignities” (our attempt at minimizing them). But how “petty” are they when one, two, or ten ambush you every day—on the treadmill, driving, waiting for the doctor? Ambushed. And it feels unmistakably physical although what you are recoiling from is merely a memory. You can tell yourself it was 30 years ago, everybody else involved is long dead, and it didn’t amount to crap, anyway, but you are stuck with it apparently all your life. Why, why did you do it? Well, did you actually do something awful?

It makes no difference that my life has been (relatively) sheltered: no military service, no trial, no jail, never a victim of a crime, never resident in a country torn by war or repression, never a stint as a male stripper. Unfortunately, that is irrelevant to vulnerability to cringe. Arguably, in fact, the less major stress in our lives, the larger loom the “trivial” embarrassments that have the power to make us squirm forever after.

Evolutionary biologists see the experience of “cringe” as linked to our survival instincts and our highly social nature.

A huge amount has been learned in the last two decades about types of memory, memory formation, and memory reconsolidation. Psychologists and neuroscientists are now beginning to pin down in impressive detail processes behind this extremely common phenomenon. (Although as recently as 2015, an article in Neuroimage began: “The neurobiology of how humans process situations that trigger their embarrassment, and how this contributes to social anxiety disorders, remains largely unknown…”)

The ways our brains seem to be wired to replay these moments suggest reasons beyond mere self-torment. Unsurprisingly, evolutionary biologists see the experience of “cringe” as linked to our survival instincts, our highly social nature, and the way our brains process long-term memory, self-consciousness, and emotion. If we could permanently erase these humiliating recollections, or prevent them, we would lose an essential part of what makes us human.

The Social Brain and the Origins of Cringe

It is not surprising that our cringe response may stem from social emotions, the ingrained responses by which we navigate relationships, maintain reputations, and avoid exclusion. Evolutionary psychology and common sense suggest that early human survival depended on being part of a group. A lone individual was far more vulnerable to threats than a member of a well-integrated social network. As a result, our brains evolved to monitor social interactions obsessively, attuning us to how we are perceived by others as if our lives depended upon it—as they did.

This mechanism probably once helped us learn from social missteps, ensuring we didn’t repeat behavior that could lead to the dangers of exclusion or rejection.

Our medial prefrontal cortex and anterior cingulate cortex seem to take a lead role in social cognition, our ability to interpret and react to social situations. Brain scans by Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) show that these regions activate when we think about ourselves, imagine how others perceive us, and recall past interactions. When we replay an embarrassing memory, the same brain areas light up as though we were right back there when those feelings of shame, regret, or humiliation were actually being triggered.

This mechanism probably once helped us learn from social missteps, ensuring we didn’t repeat behavior that could lead to the dangers of exclusion or rejection. Today, at least where the modern world is relatively safe and civil, where social interactions are complex and reputations are shaped by fleeting moments (including online), this protective mechanism can feel like an overactive alarm system, keeping us haunted by relatively minor social slip-ups.

Why Some Cringes Linger

Not all embarrassing moments linger in our minds. Some fade quickly, while others seem permanent, surfacing again and again. Why?

One explanation comes from contemporary research into the role of emotional intensity in memory consolidation. Neuroscientists fairly early on discovered that the amygdala, part of the brain’s emotional processing center, sees to the strengthening of memories that are linked to strong emotions—whether joy, fear, or embarrassment. When an experience provokes a high level of emotional arousal, the amygdala interacts with the hippocampus, a chief memory region, to enhance the encoding and storage of that memory. In effect, our intensely embarrassing moments may become “tagged” as significant, making them more likely to be recalled in vivid detail. One strong finding is that “increasing levels of stress are required to form long-lasting memories that are proportionally stronger and more persistent….the levels of the stress hormones noradrenaline and glucocorticoids… mediate and modulate memory retention…” [Emphasis added]

A related process is “reconsolidation” that occurs when memories are recalled. Each time we relive a cringe moment, for example, the memory is rewritten, strengthening the neural pathways associated with it. This can become a kind of loop; the more we dwell on an embarrassing memory, the stronger and more persistent it becomes. A leader in this research when I was editor of Cerebrum: The Dana Forum on Brain Science was Columbia University neuroscientist Eric Kandel, MD, who went on to win the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2000.

A Trip to the DMN

The Default Mode Network of interconnected brain regions becomes active when we are not focused on external tasks—in other words, essentially our prefrontal cortex, center of executive functioning, is on coffee break—and our minds are wool-gathering, daydreaming, or reflecting. But the DMN, which has been described as “an ensemble of cortices”) also is involved in autobiographical memory and self-referential thinking. Thus, it is often responsible for those unwelcome “cringe attacks” that seem to pop up out of nowhere when we let our minds drift. In such moments, the DMN frequently return to “old business,” unresolved moments of social embarrassment, replaying them in high definition like police examining a security camera tape.

Interestingly, research suggests that people with heightened DMN activity (going out of conscious mental focus) may be more prone to rumination—a neutral term for constantly re-examining past experiences—that sometimes reaches the point of distress. This overactive self-reflection (“rumination”) may contribute to anxiety disorders, depression, or social phobia, where cringe memories escalate from daily passing discomforts into ongoing distress.

Is This Social PTSD?

Although the term “trauma,” and post-traumatic stress disorder, are often reserved for severe, life-threatening experiences, it appears that social humiliation and rejection can have long-lasting psychological effects. The brain processes physical pain and social pain in overlapping ways; fMRI studies have shown that the same neural circuits that respond to bodily injury are also activated when we experience social rejection or humiliation. (“I could have died of embarrassment.”)

“Some regions responded to stories involving physical states, regardless of painful content (secondary sensory regions), some selectively responded to both emotionally and physically painful events (bilateral anterior thalamus and anterior middle cingulate cortex), one brain region responded selectively to physical pain (left insula), and one brain region responded selectively to emotional pain (dorsomedial prefrontal cortex).”

Back in junior high school in my hometown in central Massachusetts, then still a farm town, the guys were walking back from “shop” class—for some reason held in a house across the athletic field, up a steep dirt path, and across a street. We were almost back to the school building, on the basketball court right behind it, when Griffith, the persecutor of nerds (like me), cried out, “Pants him!”

That “him” was me. I barely looked around in panic before three guys were behind me, holding my arms, and Griffith was in front of me. So, my trousers and underwear came down and were hauled over my feet. Imagine for yourself my struggles, pleading, anguish. Pants and underwear went up, up over the basketball hoop. The guys headed back to class.

Later, Miss Carlin came out looking for me. Where had I gotten lost between shop and school? No one was telling. I was sitting on a low concrete wall, face in hands. When she spoke, I jumped. What to do? Miss Carlin was young and pretty, a kind of heart-throb of the guys. She was helping me up and observing my state.

Fast forward 50 years, I am on the treadmill in the Recreation Center, my daily routine, 30 minutes, 2.7 mph, 7.0 slope, seeking relaxation, but I am back in Holden, Massachusetts, Miss Carlin tenderly, gently helping me up, checking my “manhood” for any worse damage than public exposure.

And so, my half-hour of relaxation becomes a gantlet run, blow after blow falling. My own timid victimization (shame cringe). My fantasies of what I should have done to Griffith (reproach cringe). And stirring recollections of Miss Carlin and what if… (regret cringe).

A witch’s brew of brain chemistry that I couldn’t outrun even if I could still run.

Some psychologists propose this is a mild PTSD response. The brain treats these experiences as threats to our social standing, replaying the events to prevent future mistakes. Unlike full-blown PTSD, the perceived “threat” of social embarrassment never fully resolves because the consequences are largely internal and subjective rather than external and tangible.

Can the Squirm Turn?

If embarrassing memories are inevitable, is there a way to fight back against their periodic hijacking our thoughts?

If embarrassing memories are inevitable, is there a way to fight back against their periodic hijacking our thoughts? Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and practiced “mindfulness” at least suggest strategies for minimizing their impact:

- New frame, new perspective? CBT might direct us to drag those cringe memories into the light, replay them deliberately, and reinterpret them. How would you judge someone if you witnessed it happening to them? Most often, your avalanche to them was a pebbling rolling down the hill. If they are still alive, they forgot it ages ago. Reframe the scene in third person and judge yourself objectively—as you could not at the time.

- Over-expose the negative? Along the same lines as CBT, there is therapy for treating anxiety disorders. It involves repeatedly recalling an uncomfortable memory in a safe, controlled setting, where the brain can process it without triggering a stress response. Over time, this can reduce the emotional sting.

- Try to take charge? Observing your own thoughts and feelings in real time, sometimes called “mindfulness,” you can learn to monitor your responses to cringe memories without becoming emotionally entangled in them. This is a slightly different approach to breaking the cycle of automatic negative self-evaluation.

- Give a hoot and yourself a break? Cringe feeds and flourishes on self-judgment, but humor and self-compassion can neutralize its power. Here we are reframing the moments that haunt us but focusing on how funny they often are. We are fitting them into what has been called “the human comedy.” By sharing embarrassing stories with friends and observing and joining in their laughter at them, you are rewiring your brain to view them as less threatening.

Psychologist Ellen Hendriksen concluded a recent article in Psychology Today on ways to cope with cringe attacks: “All-in-all, re-think cringe attacks as something that happens to everyone—you, me, and every person reading this—and therefore connects you to a universal and oh-so-human experience.” Consoled?

“Hello, Cringe, My Old Friend…”

“Come to visit me, again?” Our evolutionary biology does not change very fast; everything we read about the Roman Empire and ancient Greece is us. The second hand of evolution barely has ticked since then, so cringe appears to be an inescapable part of being human, our brains being wired to protect social belonging, with deviations punishable by psychic pain. How to make peace with the cringe? Maybe try to make friends with these perdurable memories, one proof of our growth, learning, maturity, and the blessed capacity to laugh at folly. Perhaps take the pledge with G.K. Chesterton:

“My friends, we will not go again or ape an ancient rage,

Or stretch the folly of our youth to be the shame of age,

But walk with clearer eyes and ears this path that wandereth…”