Translating deep thinking into common sense

The New Barbarians on the Postmodernist Campus

By Walter Donway

September 30, 2018

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

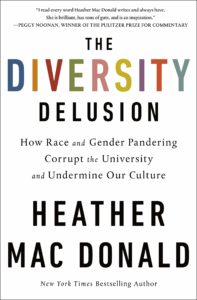

Part III of a three-part book overview of:

The Diversity Delusion: How Race and Gender Pandering Corrupt the University and Undermine Our Culture by Heather Mac Donald: New York City: St. Martin’s Press, 2018.

Part I of this book overview was “High-Tuition Tribalism.”

Part II was “The New Epidemic of Fictitious Campus ‘Rapes’.”

“But the students currently stewing in delusional resentments and self-pity will eventually graduate, and some will seize levers of power. … Unless the campus zest for censorship is combated now, what we have always regarded as a precious inheritance could be eroded beyond recognition, and a soft totalitarianism could become the new American norm.”

– Heather Mac Donald

Does that sound like an apocalyptical prediction? The volume increased to get attention in today’s cacophony of threatening voices? Actually, by the time I finished reading The Diversity Delusion, this statement raised only one question in my mind. Why would it be “soft” totalitarianism?

The default tactic, when students under the spell of postmodernist philosophy and its neo-Marxist premise of omnipresent “oppression” are challenged by any dissent, is violence.

After all, the default tactic, when students under the spell of postmodernist philosophy and its neo-Marxist premise of omnipresent “oppression” are challenged by any dissent, is violence. If the university, the supposed citadel of reason, argument, and pursuit of truth, has become a haven that shelters and excuses student initiation of force for political ends—including marching into the classroom to surround the professor and scream in his face—why are we looking at “soft” totalitarianism?

When an obsession with race and gender—under the rubric of social and economic egalitarianism—increasingly dominates the college curriculum, student life, and student “mind space,” then obviously something is displaced. That something is simply a matter of time, attention, and budget. And the something is what Mac Donald refers to as a “precious inheritance”: the knowledge, the culture of arts and science, and the supreme value placed on reason by that most dearly bought of our blessings: “Western civilization.”

Heather Mac Donald

Source: Manhattan Institute

“Until 2011, students majoring in English at UCLA had to take one course in Chaucer, two in Shakespeare, and one in Milton—the cornerstones of English literature. Following a revolt of the junior faculty, during which it was announced that Shakespeare was part of the “Empire,” UCLA junked these individual author requirements and replaced them with a mandate that all English majors take a total of three courses in the following four areas: Gender, Race, Ethnicity, Disability, and Sexuality Studies; Imperial, Transnational, and Postcolonial Studies; genre studies, interdisciplinary studies, and critical theory; or creative writing.”

UCLA’s had been the most popular English major in the country,” Mac Donald explains, “enrolling a whopping 1,400 undergraduates.”

This was not the first such academic coup d’etat, not by a long shot. And this review could quote dozens of examples of naked clashes between modernism (the culture forged in the Renaissance and Enlightenment) and postmodernism (the product of the German anti-Enlightenment revolution that a century ago began to take over the U.S. academic world). The clashes are almost uniformly resolved in favor of postmodernism because not arguments but charges of racism, sexism, white male chauvinism, and defending white male privilege—to take a mere sampling—are used to intimidate dissenters.

The very term [Western Civilization] grates on postmodernist intellectuals, including college faculties.

Never content to merely assert, Mac Donald embraces the ambitious project, in this book, of advocating for the value, relevance, and, yes, beauty of the Western cultural legacy. And advocating not in general terms, but idea by idea, even quotation by quotation. As though calling upon her legal training (at the Stanford University School of Law), she presents the evidence to the jury. It is an impressive and enjoyable performance, although as she characterizes the UCLA junior faculty response to such stuff as “Ho-hum.”

To mount a defense of the humanities, the sciences, the arts including music and poetry, history, and command of logic and language is ambitious enough at book length but Mac Donald succeeds because of her own contagious reverence for the best the human mind has produced. I will not try to summarize her summary, here.

Oh well, at least the kids are absorbed, today, because their studies are closely related to their lives and experiences, right? Perhaps not. There are two phenomena that may well be related. The first, I have described: the gutting of the traditional curriculum in favor of identity studies. The second is the repeatedly lamented “crisis of the humanities.”

“A 2013 Harvard report, cochaired by the school’s premier postcolonial studies theorist, Homi Bhadha, lamented that 57 percent of incoming Harvard students who initially declare interest in a humanities major eventually change concentrations.”

The ungrateful wretches! And all we’ve done to make the curriculum “relevant”!

In effect, this is the market at work. Students still have a choice. I wonder for how long? When I attended Brown University during the 1960s, there still was a “distribution requirement” for the first two years, a required menu of courses in the humanities, social sciences, sciences, languages, and English composition. I was still at Brown when a fellow student, Ira Magaziner, instigated a study and report that led to the jettisoning of all requirements. I am not sure to this day how students managed to persuade the faculty to relinquish all effective direction of their domain: the course of study.

It would be surprising if postmodernist preoccupations had remained on campus. Of course, they have not. Mac Donald looks at many examples, such as how the politics of identity have taken over hiring for leading symphony orchestras (can’t be stuck with white male music)—and the rewriting of opera classics to make obeisance to race and gender.

Has American culture, then, gone over a cliff? Much of the professoriate, more with each younger generation, as well as intellectuals (I use the term very loosely) in the media, have either bought into postmodernism or been stampeded into it by the pressure of political correctness, and terror of character assassination for bigotry. And students emerge after four years or more (many take six years to struggle through) indoctrinated.

Has American culture, then, gone over a cliff? Much of the professoriate, more with each younger generation, as well as intellectuals (I use the term very loosely) in the media, have either bought into postmodernism or been stampeded into it by the pressure of political correctness, and terror of character assassination for bigotry. And students emerge after four years or more (many take six years to struggle through) indoctrinated.

In fact, says Mac Donald, in a hopeful and illuminating chapter, “Great Courses, Great Profits,” by the yardstick of choice in the marketplace, the demand for mastery and enjoyment of learning is red-hot among Americans.

The Great Courses, originally called The Teaching Company, was started by a young entrepreneur not as an antidote to today’s politicized higher education but because he assumed that the university existed to “transmit to the young everything the civilization has figured out so far and to discover new things.” And that there ought to be real money to be made by offering that to everyone, of any age, at home or driving to work, at a university or at an overseas army base.

He was right. There was money to be made; the company has become highly profitable. But wrong about the mission of the university.

Tom Rollins’s great problem, when he began the company in 1989, was to find professors who were not “to the left of Karl Marx.” Not that he cared if that was their own political stance; he just wasn’t going to permit them to waste valuable tape time lecturing on the assumption that the customers were racist and sexist.

The company had its tough struggles getting professors to teach and not to get off their chest personal views of “burning issues” that, said Rollins, “no one would listen to except students.”

What pulled the company through, and boosted earnings into tens of millions after a decade, was an audience—mostly older professionals with successful careers—that viewed the liberal arts as a life-changing experience. To them “It was like intellectual crack,” said Rollins.

What pulled the company through, and boosted earnings into tens of millions after a decade, was an audience—mostly older professionals with successful careers—that viewed the liberal arts as a life-changing experience. To them “It was like intellectual crack,” said Rollins.

As the company became a force in education, it could provide an income to the best, most compelling teachers that began to exceed their salary. The company lost its initial deferential modesty toward scholars and required course outlines that could be reviewed, focused on the subject, and adhered to in delivery. It goes entirely without saying that college administrators, including department chairmen, would not dream of such management of what their university offers to students for their tuition dollars.

But fame stirred opposition in academia. “So totalitarian is the contemporary university that some professors wrote to Rollins complaining that his courses were too canonical in content and do not include enough of the requisite ‘silenced’ voices.”

Mac Donald does not restrain her irony. “Of course, outside the academy, theory encounters a little something called the marketplace, where it turns out that courses like ‘Queering the Alamo,’ say, can’t compete …”

From the uplifting report that a craving for mastery and enjoyment of new knowledge, especially Western culture, remains powerful in the American sense of life, Mac Donald returns to the embattled university and the “progressive” corruption of its mission.

In 2016, soon after Donald Trump’s election, Yale University’s president addressed freshmen on the mission of education at Yale. Guess what that mission is? It is to teach students to recognize “false narratives.” Narratives that “exaggerate or distort or neglect crucial facts.” I’m not kidding. He repeated several times that such narratives evoke “anger, fear, and disgust” in students. (“It was impossible not to hear a reference to Donald Trump,” Mac Donald comments.)

So, what would Yale do for its freshmen? What its faculty does best, the president assured them, which is to teach “stubborn skepticism about narratives that oversimplify issues, inflame the emotions, and misdirect the mind.”

There, in a phrase, is how Yale views its mission, today. It is almost beyond belief that his audience could keep a straight face, but, of course, they were freshmen. Mac Donald captures the absurdity of the moment: “… it is hilariously wrong about the actual state of ‘stubborn skepticism’ at Yale.”

For an instance of Yale’s “stubborn skepticism,” she takes us back to October 2015. Yale’s diversity bureaucrats had issued directives to students guiding their choice of Halloween costumes. This was necessary to avoid both racism and its mirror transgression of ‘appropriating’ minority cultures. The wife of a college master (a professor living in a dorm), failing to grasp the gravity of the matter, sent an email to students suggesting that they were capable of choosing their own Halloween costumes without advice from the diversity police.

Yale’s minority students, and others nationwide, exploded. Their very being was threatened, they raged. There were angry gatherings across campus. One mob waylaid and surrounded the college master on campus, “cursing and screaming at him, calling him a racist, and demanding that he resign from Yale.”

It was a time of nationwide demonstrations by Black Lives Matter and this incident became a flash point. Yale’s president, says Mac Donald, “groveled.” He circulated a letter to the whole campus heralding the urgent need to work “toward a better, more diverse, and more inclusive Yale …” He thanked the protesting students for the opportunity to listen to them and learn from them. He pledged that the campus had no place for “hatred and discrimination.”

He announced, writes Mac Donald, that “the entire administration, including faculty chairs and deans, would receive training on how to “combat racism at Yale …” and he would throw another $50 million into Yale’s diversity programs.

Professor Nicholas Christakis and his wife, Erika, humbly apologized to students in their residential college.

Not only was this a prime opportunity for Yale’s president to exhibit the “stubborn skepticism” about “false narratives,” it was time to head off a literally delusional mindset among students. “If ever there were a narrative worthy of being subjected to ‘stubborn skepticism,’ ” writes Mac Donald, “the claim that Yale was the home of ‘hatred and discrimination’ is it. During the hours-long scourging of Nicholas Christakis, a student loudly whines ‘We’re dying!’. … There never has been a more tolerant social environment in human history than Yale (and every other American college)—at least if you don’t challenge the reigning political orthodoxies.”

Yes, both the most tolerant social environment—and the least tolerant intellectual environment.

Not only is battling false narratives not remotely today’s mission of Yale, says Mac Donald; but even where practiced, it is not the mission of the university. That mission is to discover knowledge and to convey that knowledge, in all its scope, power, complexity, and beauty to new generations. Generations that come to college for a supremely privileged four years devoted to learning—before the demands of work, family, and citizenship make their claims for many decades to come.

The disaster was that those who neither understood nor cared to understand what Rome had achieved, nor what that achievement required, were both inside and outside the civilization. The guardians of civilization were losing the battle among themselves, and within their own minds, before Rome lost the battle at the barricades.

With a little elbow room for imaginative projection, one can hear in The Diversity Delusion the anguish of those who saw Roman civilization sinking under the waves of the barbarianism overflowing every border, outpost, and bastion of Roman law and culture. The disaster was that those who neither understood nor cared to understand what Rome had achieved, nor what that achievement required, were both inside and outside the civilization. The guardians of civilization were losing the battle among themselves, and within their own minds, before Rome lost the battle at the barricades.

The analogy holds (I hope) only in the feeling that what is being lost is what is best in our time and place.

On the same University of California Berkeley campus where today’s students feel privileged to riot in the name of “victimology,” Mac Donald calls our attention to the façade of the Law School, which has a quotation from a 1925 speech by Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo. It reads, in part, “You will study the wisdom of the past, for in its wilderness of conflicting counsels, a trail has there been blazed. You will study the life of mankind, for this is the life you must order, and, to order with wisdom, must know.”

Mac Donald writes: “No law school today, if erecting itself from scratch, would think of parading such sentiments on its exterior. They are as alien to the reigning academic ideology as the names of the great thinkers, virtually all male, carved into the friezes of late-nineteenth-century American campus buildings. …

“They present learning as a heroic enterprise focused not on the self and its imagined victimization but on the vast world beyond the self, both past and present. Education is the search for objective knowledge that takes the learner into a grander universe of thought and achievement.”