Translating deep thinking into common sense

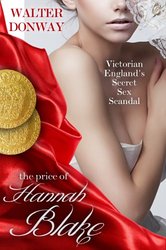

The Price of Hannah Blake (fiction)

By Walter Donway

January 3, 2016

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

The Duke had let it be known that he found tiresome the proper performances offered the public: the coy, euphemistic allusions to sex and the body itself; the priggish morality of “do” and “don’t”; and the fashion on stage, as elsewhere, to conceal every contour of the body. To watch the realm’s most glamorous actresses and dancers on stage talking like school girls or country parsons, and clad like nuns, the Duke said, put him to sleep in the royal box. It was an exaggeration, of course; but his listeners discerned the shape of a truth concealed within it—the truth in the Duke’s trousers. And, he then added, his voice dropping to a whisper, he did not give a bent farthing for the strictures of his sister, the Queen. (Some reported the Duke actually had said he didn’t give “a big fart” what the Queen thought.)

An enterprising court toady, now scarcely remembered, saw in this plaint his opportunity to become a favorite. He arranged for substantial sums to be conveyed to those actors and actresses most beloved of the public if they would consent to a private performance of a ribald type for an audience unspecified but hinted to be of the highest station. But these fat purses were returned to him, with stiff gestures, or in silence, nor could he resort to threats against public personages who were the darlings of scribblers of Fleet Street.

Persistent, as well as clever, the toady proposed that an entire company of thespians and dancers be created using the comeliest boys and girls of the kingdom to perform for the exclusive enjoyment of the duke. Being unknown, of poor family, these youths and girls could be purchased by agents of the Duke, as they were purchased for the brothels, or simply snatched (“impressed into service” was the phrase he chose). Many could be found in orphanages, workhouses, and prisons, and without great expense. Such disappearances raised no troublesome outcry.

Once enrolled in the Duke’s troupe, of course, they could not be allowed at large ever again since the narrow and righteous opinion of the public, and the Duke’s own sister, would be goaded into a holy frenzy of indignation, hypocrisy, and cries for blood at the revelation of such goings on.

Persuaded to this scheme, the Duke oversubscribed the required sum, a fortune sufficient to refurbish a grand manor and high-walled grounds on the sea in the south of England. The work went under cover of a story about preparation of a summer residence for the Duke, so that the carpenters, masons, plasterers, and gardeners who flocked to the site had no inkling of the true purpose of their work. Nor did construction of guardhouses and sentry stations within the vast grounds occasion much gossip. All accepted that a duke would wish to safeguard his person and his gold.

The Duke soon visited to view progress and merely nodded; he then fixed the toady with a glinting eye, and said, “Do what you must, but I shall have no young man or woman less than 18 years of age—for my own youngest, Charlene, at 17, is still but a child.” The toady solemnly nodded. Soon scouts rode through the kingdom, but with particular attention to impoverished rural towns in Devon and Somerset, the Lake Country, and Wales, as well as to the miserable East End of London, where ships docked daily at Wapping to disgorge bewildered, nigh helpless women traveling alone, including many fleeing pogroms in Poland and Russia.

A few boys and girls, just 18, were purchased from parents desperate in their poverty to save their remaining children. Others were seduced at the wharf at Wapping with offers of employment; some were curtly requisitioned from the East End brothels on pain of closure by the police. And so the compound beside the Channel, its gardens blooming already with mature transplants, became alive with young men and women of beauty who had disappeared from the world and now were the charges of stern teachers who disciplined the body, voice, and sensibility.

Each, according to his or her capacity to accept bitter reality, in time accepted that they never would see their families or any home they had known. The mansion with its dormitories, practice areas, theaters, quarters of the Duke’s staff, guardhouses—and much more—part palace, part school, part prison—was their home. And what occurred within its walls resembled nothing any had seen, or imagined, or visited in dreams and nightmares.

It was a mark of the Duke’s warmest favor and trust to be included in the audience for these performances. Works created for them—much dance, but also comedies or tragedies, farces or morality plays—led always (and with no great delay) to scenes that required young actors and actresses to disrobe and mimic or engage in every erotic fantasy of the suppressed Victorian psyche— though not always to the Duke’s liking. “This is but Gilder’s dreary play of last season in London,” he fumed. “Performed bare-arsed by angels, but a no better play!” Once, during an intermission, he commanded that a play’s absurd dialogue be omitted entirely during its second half, the players performing in silence but for the nude ensemble’s musical accompaniment.

Undistracted by dialogue, the Duke became so enchanted by the leading lady that he summoned her to his box at the play’s conclusion. His courtiers ushered to him a tall, raven-haired girl, not yet 20, still sweating from her exertions, her lovely face heavy with stage make-up. She had wrapped herself in a robe, though her feet were bare, and, being brought before the Duke’s entourage, she stood with that poise instilled by months of relentless drill of the body in dance. Frankly appraising her, the duke remarked, even before she had curtsied, “I did not command that she be gift-wrapped!”

The girl merely smiled, and, with grace, shrugged off her robe and let it slip to the floor. She stood naked before her exclusive audience and made a curtsy worthy of a countess. The duke boldly inspected her fine breasts—pale, but with blood-dark nipples that reflected the coloration of her raven hair. His eyes fell, then, to the trim black triangle at the base of her belly.

The Duke was not bad looking, still in his fifties, tall but heavyset, with broad shoulders; in photographs, he looked formidable. Neither his chestnut mustache and goatee nor his hair, with a generous part on the left, had become grizzled. His eyes were direct, open and inquiring—if not frankly challenging. It was the gaze of a man who had not put boyhood and its mischief quite behind him. The gaze could flash with humor, but, more often, with a covetousness accustomed to being satisfied. He did not say, “I should like to have that,” but always, “I shall take that.”

His hands were large and well manicured, but stayed in his lap; he was not given to gesturing. Still, he was a sportsman, a hunter, a horseman, even an amateur pugilist—and exercise stimulated and fueled his libido. His sister, in a rare display of daring, had given him a fine drawing of the nude Leda from her own collection of drawings, mostly of nude males. She understood her younger brother; she simply did not approve—or that is the impression she chose to give.

Now, the Duke said, “I shall entertain her in my chambers in one hour.” He did not glance at his watch; the girl would be there even if he did not arrive for two hours—or five—and she would be naked. The girl smiled, curtsied again, and was led away; the robe lay where it had fallen. The Duke inquired as to who had been responsible for the girl’s instruction, and, being told, directed that a purse be delivered to that person with the Duke’s compliments. It was a fortune, indeed, and an eloquent message to all who were responsible for the Duke’s troupe.

Thenceforth, it was understood that on any evening the Duke might fancy the company of a performer of either sex. His gifts were extravagant and his favor assured that a lad or lass took lead roles in future performances. It was less clear where the favored youth could spend the newfound wealth— confined forever to the mansion. In truth, it was promptly “requested” by the staff for the troupe’s treasury.

The Duke and his guests never tired of these performances, at first only during summers, but soon on weekends all year. And so year after year the Duke’s troupe fed on lives of the realm’s youth.

Therefore, there was nothing surprising about the Duke’s request one afternoon, as his clarence with matching white pair rolled through a market town in Devon. He was glancing from a window— perhaps in annoyance at the milling crowds—and looked into the face of a farm girl with a wicker gathering basket of carrots who had paused to let his carriage pass. She was tall, with a small waist that made her shoulders seem wider, and with a carriage straight to perfection. It was the untutored grace of a well formed country girl. Her shift of rough grey wool left a bit of her shoulders and chest uncovered; both were freckled from days in the sun. She held her head with the same natural poise, her sandy hair, bleached by sun, falling over her shoulders and down her back. Her face had the beauty of an oval—yet with a broad forehead. Her nose, too, was nearly classic, but with a slight tilt and her lips not exceptionally large, but full. It was an open face, as inquiring, even interrogating, as the Duke’s, but it was an interrogation of curiosity instead of imperious boldness.

For a moment, she returned the Duke’s gaze with a candid stare in her light blue eyes. It was evident from the grandness of the carriage, and its accompaniment of mounted men, that this was royalty. She had never seen a duke and did not recognize the face frowning back at her. Suddenly, she started in alarm at the apparent insolence of her gaze—and that this powerful man returned it steadily. Looking down, she hurried on her way— but it was too late.

Even as she hustled into the crowd, the Duke thrust his large, bearded face from the window and called to the captain of his guard, “Follow that girl. Do not molest her. Find out who she is and where she resides. Do not be noticed, and report to me. Do not fail me, in this.”

To be a cheerful 18-year-old farm girl in rural Devon made no sense. Even in the best of times, Hannah Blake’s family aspired only to have enough bread and milk at two meals for everyone —and there were seven children, the younger ones tied at three girls and three boys, with Hannah, the oldest, breaking the tie in favor of the girls.

There had been more to eat, a little more, when times were better before Hannah’s father was lost at sea two years earlier. There had been some fish, from the boats at Plymouth, and some money, when daddy would return from sea bringing his pay. That is when they had bought the pig and the four Sussex chickens, added to the one-room cottage, and Hannah had bought one or two cotton drawers, not wool.

She had even attended the free board school for six years, baffling teachers and parents with her passion to read. Had she not learned so much, in so short a time, there would be no one, now, to help the younger children and care for them after school —when Hannah was not working in the tiny garden, doing chores, or walking to market in Torridge to scour the stalls for bargains. In winter, there was less to do outdoors and more time, during daylight, to teach the little ones letters, writing, and sums.

Now, there was not enough bread or milk, especially in winter. In summer, there was the garden, with vegetables to eat or take to market; berries, fish the boys caught, and gleanings of corn and wheat from the harvested fields. The hens gave eggs, some days, but what was there to feed them? So little that in winter the cow had to be “dried” just to survive. At harvest and holidays, the landlord might make a gift of apples, honey, and even pork; but this was not without its vexation. Hannah was a beauty, now quite old to be unmarried, and the landlord seemed to fancy that she yearned for what he would like to provide. She did not; but she thought she could parlay smiles, soft looks, and jokes into more gifts to keep the family going. It seemed to work, if she feigned naivety so total that no suggestion, no hint, seemed able to penetrate it. So far, the man had not dared ask in no uncertain terms for what he craved; this beautiful but infuriatingly obtuse lass might report it in horror and confusion to her mother or even the minister.

Of course, the mother, too, he noticed, had some of Hannah’s looks—the eyes, lips, slender legs, and a bosom that rose like a high-breaking wave from her still-slim waist. The problem with the mother, he complained to companions at the Black Pony, was that haughty confidence of a woman aware of her beauty. And, said the man, “She will wait for that sailor to come home until she is neither use nor ornament.”

But still, he brought the gifts, more than to other tenants, because he could not get enough of the attention of handsome women and because Hannah’s mother also “gave” in her own way: a little flattery, a little teasing, and a way she had of turning, or reaching to a high shelf, that made him dream of her breasts when he was bedding his own wife. He would have liked more. Someday, if things became desperate for Hannah’s family…

In truth, they already were desperate. Less food in summer, less “extra” in autumn to store, and people dying more often, and younger, it seemed, in winter. Hannah’s mother was a fair seamstress, but there were too many seamstresses, now, and not enough women who could afford their work. And she was a fair midwife, but, more and more, families who could afford to pay for her services used a “real” nurse, as they put it, or went to one of the new lying-in hospitals. And Hannah’s skills were much the same—except midwifery, of course. All Hannah had in addition, her mother knew, was the face, the desirable body—a few years of bloom, while young—and Hannah’s mother was not going to bargain that away. She had never sold her own looks, after all, though in London, when she was there, it was said thousands of women did sell themselves, legally, in the brothels or following the army camps or walking the East End after a day’s work in the factories. No, she had given her beauty, and heart, to Edward Blake for love—and that, it seemed, God had taken from her, somewhere at sea, though she never heard where or how.

Why Hannah had not married years ago, she could only guess. The girl was aware of her charms: the walk, the smiles, the confidence with men who never could stay away from her at the markets and fairs, the little hint of superiority in her voice when she talked about the farm boys or shop boys or even older men like their troublesome landlord. Perhaps she did not marry because, with her father gone, who would care for youngsters, the garden, work odd jobs about town, go five miles to market—and keep her mother company with “woman talk”? Perhaps Hannah’s mother must tell her to find a husband or at least act as though she wanted one. But then, who would help to keep the family going—barely going?

So, when two men, refined in dress and speech, with horses no one in the village could afford, rode up to the cottage when she was home alone, Hannah’s mother listened to their unctuous persuasion, their “pitch,” only until she got the point. Hannah was a beauty, a fine girl who could have a career in London, where there was education and opportunity—perhaps big opportunity at the court, in the theater, who knew? Very sympathetic to the situation of Hannah’s mother, they seemed, knowing she had lost her husband, had seven children, must be hard pressed… So, to make it right, with her, for losing Hannah’s help, they were prepared to pay—they named a sum so huge that Hannah’s mother almost laughed aloud—to secure the family forever.

Hannah’s mother could not read much, but, like Hannah, her mind drove at the meaning of things and she was not naive. She was not, she said to herself, now, a stupid wench for men to trick. These men were offering to buy Hannah—and not because they were eager to provide her with “opportunity.” If her husband were here, she thought, he would throw them out, literally; but now that was up to her.

She stood straight, staring with blue eyes gone cold, and said: “I do not sell my daughters to brothels! Nor does England buy and sell women any longer—not even the Africans! I understand that our Queen, and Parliament, too, are cleaning the shit—” she came down hard on the word— “from the East End. Find yourselves another line of work. The days of whoremongers are at an end! Good day, gentlemen.” Long before she finished, the two were protesting, raising their hands to fend off this dreadful misconception. They were shocked that anyone could so mistake their motives, and…

“Good day, gentlemen!” The three words rang with the ferocity of a battle cry and vehemence of a curse. They stepped back and she advanced. One said, later, describing the incident, that when he saw her face, impassioned in emotion, her flashing blue eyes, and, above all, the breasts heaving with anger, he wondered if the duke might prefer the mother to the daughter. The other said she seemed to reach toward the hearth where hung a heavy cast-iron ladle.

She should have told Hannah. Those bitter words she repeated again and again—but only later, not when the two had turned and half-stumbled through the low doorway, mounted their fine horses, and rode straight out of the village. Then, she had nodded to herself, bosom still heaving with emotion, and said, aloud, “Can you fathom it? In this time, in England!”

She should have told Hannah—to warn her. Should not have mugged so proudly at her little victory. Should have warned Hannah that these men had come to buy her like a prime heifer at fair. But she did not. She had thought that to tell Hannah of this satanic bargain—her virtue, her soul, for the salvation of her family—might leave Hannah to wonder if her mother had been tempted. Or leave her to watch, if it came to that, the starvation of her brothers, her sisters, and to imagine herself responsible.

But she should have told Hannah. If she had, Hannah might be here today, with her… But she was not. She was gone, and to what fate her mother thought she knew—and the price had not even been paid. That final thought left her feeling wicked, almost an accomplice in what had happened to her beautiful daughter.

The excerpt above are the first two chapters from “The Price of Hannah Blake: Victorian England’s Secret Sex Scandal,” available on Amazon.