Translating deep thinking into common sense

The “Sucker Cycle”

By Mark Tier

November 17, 2018

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

The greater fool theory states that it is possible to make money by buying securities, whether or not they are overvalued, by selling them for a profit at a later date.

Investopedia defines the Greater Fool Theory thusly:

“The greater fool theory states that it is possible to make money by buying securities [or other investibles], whether or not they are overvalued, by selling them for a profit at a later date. This is because there will always be someone (i.e., a bigger or greater fool) who is willing to pay a higher price.”[1]

Clearly, those investors described as fools in this definition didn’t consider themselves to be foolish—at the time they made their investments.

That’s a label applied to them either in retrospect, when it becomes clear that the boom has busted and the assets they bought mostly turned out to be turkeys, or by those experienced investors who consider the valuations of the booming market to be totally irrational.

In a boom, a bubble, or a mania, investor behavior can be broadly categorized into three distinct types:

- The rational investor who has a distinct method of valuation and avoids any investment that does not meet his criteria. Examples include Warren Buffett, Benjamin Graham, Peter Lynch, and Sir John Templeton.

- The rational speculator, typified by George Soros, has a clear understanding of the nature of the market, and a well-defined exit strategy to bank his profits while guarding his capital against possible losses; and,

- The emotional investor who is fundamentally a crowd-follower, influenced by the opinions of fellow believers, including many self-styled investment gurus, his rationale “proven” during a boom by the continuing rise of the market.

The “emotional investor” is also making a fundamental mistake. He thinks he is investing, but is actually speculating.

The “emotional investor” is also making a fundamental mistake. He thinks he is investing, but is actually speculating. Speculating without a developed and tested trading system is rather like skydiving without a parachute: you might get lucky, but you probably won’t.[2]

Another powerful factor that acts to “validate” the emotional investors’ actions are the numerous predictions from rational investors that the market may be about to crash—or inevitably will— … while the market in question continues to zoom up, seemingly to infinity.

The rational investors are ridiculed and ignored—as Warren Buffett was during the 1990s dot-com boom when he was widely considered to have “lost his touch.”

Eventually, the rational investors are proven right. To quote Benjamin Graham: “In the short run the market is a voting machine; in the long run it is weighing machine.”

In the markets there is always a Greater Fool—until there isn’t.

Another way to put it: in the markets there is always a Greater Fool—until there isn’t.

The Greater Fool Theory is always a factor in every market, whether boom or bust. When the market is mostly rational, it’s a minor factor. In the latter stages of a mania, the Greater Fool Theory dominates.

To make this distinction clear, let’s look at the Greater Fool Theory from a different perspective. I call it—

The “Sucker Cycle”

Which is a primary component of all booms, bubbles, and manias.

The simplest way to understand the “Sucker Cycle” is to take an imaginary visit to Albania in the 1990s.

Thanks to Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of glasnost and perestroika, and the Soviet Union’s quiet abandonment of “the Brezhnev Doctrine” of propping up communist governments in satellite states with military force, the rule of communism in Eastern Europe began to unravel.

The Berlin Wall came down on 9 November 1989; East Germany ceased to exist, becoming unified with West Germany in October 1990; and other eastern European communist governments fell one after another, like dominoes, the last one being Albania’s in March 1991.

A Super Sucker Cycle

Albania in 1991 was a nation full of suckers.

Enver Hoxha ruled Albania from 1944 till his death in 1985. His version of communism was one of repression, no private property, and little (preferably no) trade with the rest of the world—a regime which continued under his successors until Communism’s collapse.

Having thumbed his nose at the Soviet Union, Hoxha cozied up to Mao’s China until 1971, when American President Richard Nixon announced he had agreed to visit Beijing to meet Chou En-lai.

In 1973, China cut off all aid to Albania—now with no friends or allies and little foreign trade, Albania was even more isolated from the rest of the world than North Korea is today.

Albania was the poorest country in Europe—as it had been for the entire Cold War period.

How poor?

In 1990, Albania’s per capita GNP of $639.50 was a mere 2.7% that of the United States’ ($23,954) and just 8.7% of the then-poorest western European country, Portugal ($7,885).

Worse was to come.

Following the collapse of communism in March 1991, inflation took off and the average town-dweller’s purchasing power fell in half.

Albanians were now not just poor, but desperate.

And ignorant.

Growing up under Hoxha’s version of communism, nobody knew anything about money, markets, investing, interest, return on equity, or anything else about money and how to make it—or keep it.

A country full of desperate suckers—ready to be taken to the cleaners by the first savvy con man.

Hajdin Sejdia’s “Hole”

His name was Hajdin Sejdia, a former economic advisor to Albania’s first elected prime minister.

In 1991, Sejdia raised several million dollars from the public to build a luxury hotel in the capital, Tirana—and ran off to Switzerland with the money leaving what became known as “Hajdin Sejdia’s Hole.”

Sejdia’s company, Iliria Holding, was the first of many theoretically legitimate businesses that borrowed money from the public to finance their activities. Attracting money with interest rates as high as 4% per month.

Some of the companies were profitable—up until the end of 1995 when the United Nations suspended sanctions against Yugoslavia, eliminating a major source of income: smuggling.

This was the spark that set off Albania’s Ponzi or Pyramid Bubble.

- In January 1996, interest rates increased to 6% per month

- In May, to 8%, and two new operations, pure Ponzis with no business activities at all—Xhafferi and Populli—opened their doors

- In July, the competition for money started a “race to the bottom”: Kamberi lifted its monthly rates to 10%

- In September, Populli offered more than 30% a month

- In November, Xhafferi promised to treble depositors’ money in three months

- Prompting Sude to promise to double people’s money in just two months

People sold their houses and farmers sold their farms and livestock to take advantage of these “investments.” Money poured in to Albania from Italy, Greece, and elsewhere in the world from Albanians who’d moved abroad.

By November 1996, the 20-odd different Ponzi schemes had between 1.7 and 2 million depositors in a country of just 3½ million people who had made total deposits of some $1.6 billion.

Clearly (to us) such payout rates are unsustainable and on 19 November 1996, the inevitable happened: Sude, the Ponzi which offered to double your money every two months, defaulted, shaking people’s confidence in all the schemes.

As a result, new deposits dried up. By January 1997, Sude and Gjallica were in bankruptcy, while the others ceased making payouts—and all the Ponzi schemes collapsed.

Just about every Albanian family was bankrupt.

We could call Albania’s Ponzi scheme blowout a “Super Sucker Cycle.”

Albania was an extreme example of the consequences of ignorance.

But it was not alone. After all, people in the other ex-Communist countries of Russia and Eastern Europe were hardly more financially literate than Albanians.

In Russia, an outfit named MMM gathered some $10 billion from millions of Russians by promising annual returns of up to 1,000%. While between 1991 and 1994 the “Caritas scheme,” promising eight times your money within six months, collected a billion or so dollars from around 400,000 Romanian suckers.

But the “Sucker Cycle” can hit anywhere, at any time, simply because four new suckers are born every second!

We Were All Suckers Once

Including me.

When I made my first investment in 1966, I was a callow and totally ignorant 19-year-old.

But of course as a teenager I was not only immortal, but knew more about everything than my parents.

Like you, I imagine, I was taught next to nothing about money and how to handle it at school and university—even though I have a degree in economics.

So, needless to say, my very first investment was a total disaster. I’d bought in at the top—or within a few cents of it—and right afterward the stock headed south until it hit zero!

What made me do such a stupid thing? Well—and I’m embarrassed to tell you, even today—I met this stockbroker at a party ….

Did I get snowed!

Looking back, I’m sure the broker was trying to unload a dud stock on any passing sucker.

And, boy, was I a sucker then.

I wasn’t even at the bottom of the learning curve—which is where most of us are when we make our first investment.

Every year millions of new adults come into the markets with dreams of getting rich. Almost every single one a sucker, just as I was when I was 19.

As, no doubt, you were when you made your first investment.

Suckers can be conned anywhere.

Doubt me?

Bernie Madoff was a conman who flourished for decades in New York, the most financially literate city in one of the world’s most financially literate countries—directly under the “watchful” eye of the SEC—which had investigated his operations several times—and found nothing.

Bernie Madoff was a conman who flourished for decades in New York, the most financially literate city in one of the world’s most financially literate countries—directly under the “watchful” eye of the SEC—which had investigated his operations several times—and found nothing. Only when two of Madoff’s employees blew the whistle was Madoff arrested and his Ponzi scheme which had scooped up $64.8 billion revealed.

Madoff wasn’t the only one. Here’s a partial list of Ponzi schemes in the United States that were closed down by the SEC or state regulators:

1983, Hawaii: An investment firm run by Ron Rewald declared bankruptcy in 1983 and was revealed to have been a Ponzi scheme which defrauded over 400 investors of more than $22 million.

1984, California: J. David & Company, a purported currency and commodity trading and investing operation, was revealed to be a Ponzi scheme.

1986, Michigan: 1600 investors in Diamond Mortgage Company and A.J. Obie, two firms with the same managers, lost approximately $50 million in what the Michigan Court of Appeals described as “the largest reported ‘Ponzi’ scheme in the history of the state.”

1993, New York: Towers Investors, a bill collection agency, collapsed in 1993; in 1995, chairman Steven Hoffenberg pleaded guilty to bilking investors out of $475 million.

1996, New York: Sidney Schwartz and his son, Stuart F. Schwartz, pleaded guilty to charges of running a multimillion-dollar Ponzi scheme that targeted members of a Long Island, New York, country club at which the senior Schwartz was a member of the board of governors.

1997, Florida: A church named Greater Ministries International bilked over 18,000 people out of $500 million. Church elders promised the church members double their money back, citing Biblical scripture.

2008, California: it was reported that John G. Ervin of Safevest LLC had been arrested by the FBI on suspicion of running a Ponzi scheme that collected $25.7 million, mostly from Christian investors, partly recruited through Ervin’s business partner Pastor John Slye and members of his church. Specifically, according to newspaper The Orange County Register, “the company recruited church members to sell the investment to other church members.”

2008, Minnesota: celebrity businessman Tom Petters was charged by the Federal government as the mastermind behind a $3.65 billion Ponzi scheme that bilked investors over a 13-year period.

2009, Pennsylvania: the SEC charged Joseph S. Forte from Broomall, Pennsylvania with masterminding a $50 million Ponzi scheme. He swindled over 80 investors from 1995 to 2009.

2009, Tennessee: the Stanford International Bank and proprietor Allen Stanford were accused of “massive fraud” by U.S. authorities, and SIB’s assets were frozen. The apparent Ponzi scheme drew in more than $8 billion of “deposits” to Sir Allen’s bank in Antigua.

2009, Ohio: 67-year-old Joanne Schneider was sentenced to three years in prison, the minimum allowed, for operating a Ponzi scheme that cost investors an estimated $60 million.

2009, Florida: Donald Anthony Walker Young had his office seized for using money from new investors to pay previous investors and using some of the money to purchase a vacation home in Palm Beach, Florida.[3]

A Sucker’s Progress

Everyone is born ignorant.

Come adulthood, we will still be ignorant about many things depending on our parents, culture, education, and what we may have learnt on our own initiative.

Almost universally one subject nearly everyone will remain ignorant of when they reach the age of consent is the best way to handle money. Especially when it comes to investing.

There are exceptions to that “rule.” Warren Buffett, for example, began learning about money when he was just 6 years old. When he was 19 and came across a copy of Benjamin Graham’s Intelligent Investor his investment education reached a level few of us achieve in our lifetime.

But the majority of us, once we have accumulated some money and make our first investment with dollar signs dancing before our eyes, know little or nothing about investing and follow one of three probable paths:

- We lose our shirts and, like the cat which burnt its paw on a hot stove, never go near the markets again.

- We lose our shirts and vow to learn more about investing. We either fail (path #2a ⇒ back to path #1) and keep out, or learn enough (path #2b) to be mildly or even wildly successful. Or,

- We make a bundle of money. Which is usually the worst thing that can happen as we now think we are experts, legendary investors-to-be in our own minds. And go on to lose the lot. Especially if our success continues for a while, as it will during a boom, a mania, or a bubble.

During a boom or a bubble, most of those suckers who come into the markets for the first time follow path #3.

And the longer the markets are booming, the greater the number of newbies who pile into the “investment du jour”—adding more fuel to the flame, pushing prices up way above any rational measure of value.

But the bad news is:

We’re All Still Suckers

Because we’re still ignorant.

Of course, the older we get the less ignorant we become. But no matter how much we know, there are still some, if not many things we remain ignorant about. There’s simply too much to know for any single person to be an expert on everything.

To paraphrase Warren Buffett, we’re all smart in spots. When we stray outside those spots—outside our circle of competence—we’re as ignorant as anybody else.

And You Don’t Have to be Dumb to be a Sucker

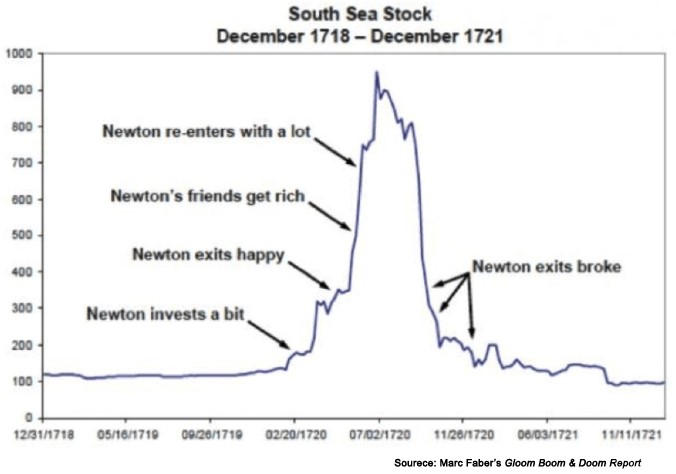

Being smart does not immunize you from making really dumb decisions. One of the world’s most intelligent men, Isaac Newton, was sucked into the South Sea Bubble—and went broke as a result!

Isaac Newton is just one of many really smart (and successful) people who turned out to be suckers.

Consider Theranos Inc.

Founded in 2014 by Elizabeth Holmes who claimed she’d “invented a device that could conduct sophisticated blood tests from a tiny amount of blood drawn from a finger prick”[4] which would replace drawing blood samples from a vein with a needle. Her blood-testing method was touted as:

“. . . faster, cheaper and more accurate than the conventional methods.

What’s more, this device didn’t even exist!

Nevertheless, a “Who’s Who” of “smart money” people were suckered into investing a bundle into Theranos—and lost the lot:

| Walton family (heirs of Walmart founder Sam Walton) | $150 million | |||

| Rupert Murdoch, News Corp chairman | $121 million | |||

| Betsy DeVos (US Education Secretary) and family | $100 million | |||

| Cox family (Cox Media) | $100 million | |||

| Andreas Dracopoulos, Greek shipping magnate | $100 million | |||

| Oppenheimer family (ex De Beers owners) | $20 million | |||

| Riley Bechtel (former chairman of Bechtel Corp) | $6 million[6] | |||

In addition, supermarket chain Safeway lent Theranos $30 million and began renovating its stores to accommodate Theranos’ blood-testing machines. While Walgreens invested $325 million to create testing centers in its stores.

PLUS: Elizabeth Holmes had lined up a stellar list of directors for her company including former secretaries of State George Shultz and former senators Sam Nunn and Bill Frist, former secretary of Defense William Perry and the current Defense Secretary James Mattis (who resigned as a director on his appointment).

Not one of these people or companies saw the “revolutionary device”—or even asked to see it with the one exception of Walgreens whose request to visit Theranos’s labs was turned down.

Talk about a hustle!

So, as Elizabeth Holmes (among many others) demonstrated, smart people can still be suckered.

How?

Firstly, we don’t always admit our ignorance. Clearly—with the benefit of hindsight—after we’ve been suckered our mistake becomes obvious and we realize we didn’t really know what we were doing.

Secondly, we can always be impressed. And Ms. Holmes’s line up of directors was really impressive. Surely, we would have thought had we been asked to invest, those people knew what they were doing.

Third: we want to believe. It’s such a great idea that the potential profits are enormous.

Finally, the great hustler is an incredible salesperson. For example, Elizabeth Holmes—

“. . . had this intense way of looking at you while she spoke that made you want to believe in her and want to follow her,” said one of her best friends at Stanford, who Holmes convinced to work for Theranos.[7]

In May 2018, Ms. Holmes was charged by the SEC with defrauding investors.

Caveat Emptor (Buyer Beware!)

That should always be your rule every time you make an investment.

If you get suckered the SEC (or equivalent in other countries) might come to the rescue.

Given Bernie Madoff and the number of other Ponzi, Pyramid, and similar hustles we’ve met so far, you can’t count on it.

More often than not, the SEC shows up after the baddies have long gone and there’s nothing (and nobody) left to save.

The SEC isn’t like the US cavalry who, in those old western movies you can still see on late night TV, gallop over the hill just in time to save the heroine or townsfolk from a fate worse than death.

More often than not, the SEC shows up after the baddies have long gone and there’s nothing (and nobody) left to save.

You might feel avenged if the SEC punishes the perpetrators—but you’re unlikely to get much (if any) of your money back.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/greaterfooltheory.asp

[2] See The Winning Investment Habits of Warren Buffett & George Soros to fully appreciate this distinction.

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Ponzi_schemes

[4] Raymond Bonner, “Elizabeth Holmes, Theranos founder, conned America,” The Weekend Australian, 7 July 2018.

[5] ibid.

[6] John Carreyrou, “Theranos Cost Business and Government Leaders More Than $600 Million,” The Wall Street Journal, 3 May 2018.

[7] Bonner, op. cit.