Translating deep thinking into common sense

We the Living Revisited

By Marco den Ouden

November 8, 2022

SUBSCRIBE TO SAVVY STREET (It's Free)

Andrei shines through as a noble, albeit misguided man. His love for Kira is powerful and all-consuming.

Several weeks ago, my wife and I spent an afternoon in Fremantle, Australia. We rode the Ferris Wheel in Esplanade Park and had a lovely seafood lunch at Kaili’s on the waterfront boardwalk. Then we wandered around town a bit, stopping to browse at two bookstores on High Street near Notre Dame University. One was Bill Campbell’s “Second Hand Books.” As I often do, I checked to see what secondhand Ayn Rand books they had. A couple of years ago I picked up a first edition of Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal this way in a bookstore in suburban Vancouver, Canada.

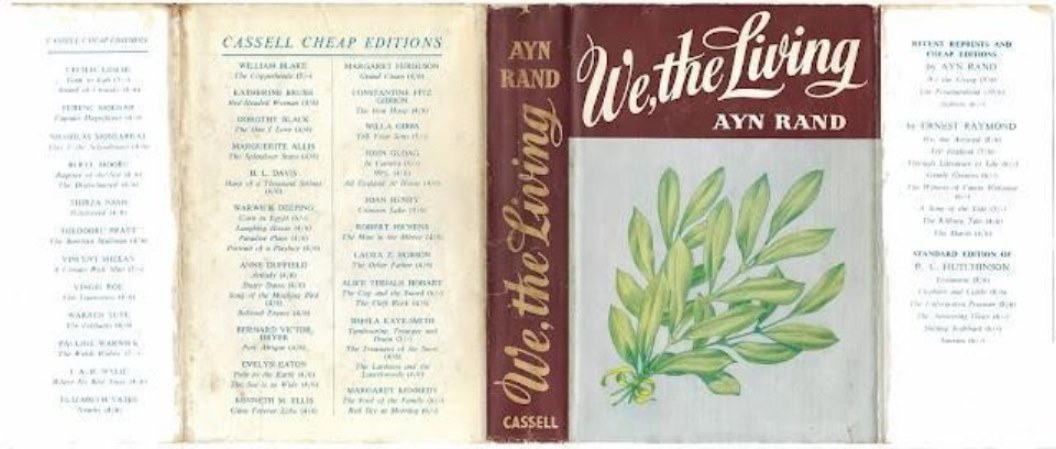

This time I lucked out again—a vintage hard cover copy of the British edition of We the Living. The British edition was first published by Cassell and Company in 1937, a year after its release in the United States by Macmillan. While Macmillan’s press run of 3,000 copies was sold out in eighteen months, the company foolishly destroyed the plates and it was out of print in the United States until reissued in an extensively revised edition by Random House in 1959. On the other hand, the Cassell edition remained in print for over a decade, consistently selling well.

In Essays on Ayn Rand’s We the Living edited by Robert Mayhew, Richard Ralston cites a letter from Cassell’s Desmond Flower to Ayn Rand’s London agent Laurence Pollinger, dated January 22, 1940:

We the Living, published in January 1937, is the only novel in our list which is still selling at the original price—exactly three years later. This is remarkable. We reprinted it again in the early summer last year, still at 8/6d, and the copies are steadily going out. Simpkins were in for more again last week. This shows an astonishing and gratifying interest on the part of the public, and I know I am not wrong in saying that we could have a really big success if we could get a new book from her. (Mayhew, 167)

In 1948 Ayn Rand wrote a summary of We the Living’s sales history when she was trying to promote the book to film producers. She wrote:

In England, We the Living was a huge success. It went into edition after edition. I kept receiving royalties for it for ten years, up to about a year ago, when it went out of print due to the paper shortage in England. Cassell’s, my English publishers, informed me that they intend to reissue the book, still in its full-price, original edition, as soon as they get the paper. (Mayhew, 167)

Mayhew writes “It sold much better than the American edition, going into at least seven printings and remaining in print until the mid-1940s,” (237)

The book also sold well in other editions, including a Danish edition and an Italian edition, which was notably pirated in an unauthorized Italian film production.

The book I snagged at Campbell’s Used Books notes on the publisher’s page that it is the “Ninth Edition 1953.”

I’m not sure if edition in British publishing means the same as printing. I suspect they are synonymous in this case. What is key here is the date, 1953. It was published after The Fountainhead and a blurb on the dust jacket flap promotes a Cassell edition of The Fountainhead.

This copy of We the Living is notable as well for its intact dust jacket. Although the title is correctly printed in the book, the dust jacket adds a comma making it We, the Living. It also has a different cover photo than the 1937 printing. The cover depicts a twig of a plant, possibly laurel. I did an extensive search on Google and could not find this dust jacket anywhere. This inability to find it and the lack of mention of a post-1948 edition in Mayhew leads me to think I may have a rare find here.

This copy of We the Living is notable as well for its intact dust jacket. Although the title is correctly printed in the book, the dust jacket adds a comma making it We, the Living. It also has a different cover photo than the 1937 printing. The cover depicts a twig of a plant, possibly laurel. I did an extensive search on Google and could not find this dust jacket anywhere. This inability to find it and the lack of mention of a post-1948 edition in Mayhew leads me to think I may have a rare find here.

I had read the revised 1959 edition in August 1973. I had not read it again since. In any event, I read this vintage edition in its entirety. It runs to 553 pages compared to the Signet paperback at 446.

The changes to the novel in its 1959 edition are well documented in Mayhew. Indeed, there were many changes between the first draft and the first edition as noted by Shoshana Milgram in her lead essay, From Airtight to We the Living: The Drafts of Ayn Rand’s First Novel. The working title, Airtight: A Novel of Red Russia, is alluded to in Part 2, Chapter XIII in Kira’s speech to Andrei after he has discovered she is Leo’s lover. The specific lines are:

You came and you forbade life to the living. You’ve driven us all into an iron cellar and you’ve closed all doors, and you’ve locked us airtight, airtight until the blood vessels of our spirits burst! Then you stare and wonder what it’s doing to us. Well, then, look! All of you who have eyes left—look! (481, [388 in the Signet edition])

One might well ask, what happened to the 107 pages missing from the Signet edition. Part of it, to be sure is in the size of the print and the typeface. But that accounts for just a small part of the text. In his essay comparing the 1936 and 1959 editions, Robert Mayhew notes:

As a brief indication of the extent of her revisions, note that she made over 900 changes in punctuation and well over 2000 changes in wording (in which I include deletions, additions, replacing individual words or rewording phrases and sentences). According to my examination, only one page (of the 1996 [sixtieth anniversary] edition) went without a single change (namely, 105). (209-210)

Mayhew discusses these changes in some detail and notes that “There were many more deletions than additions.” (219) He goes on to discuss substantive philosophical changes including Rand’s treatment of sex, capitalism and Nietzsche. He adds an appendix specifically dealing with the British edition. Changes for the British edition include spelling, e.g., gaol for jail; British terminology, e.g., lorry for truck; and a bowdlerization of some of the steamier sex scenes (steamier by 1937 standards, pretty tame by today’s standards). Other differences include song titles in italics in the British edition, and in quotation marks in the American.

In a letter to Leonard Read about the British edition, Rand wrote: “It’s the same as the American edition, except that my love scenes have been slightly censored, unfortunately.” (Mayhew, 240)

Reading the book again in a somewhat longer edition was an adventure. I found Part 1 remarkably bleak and almost depressing. Rand has said the novel is not about a love triangle, though many see it that way. It is about the individual versus the state. As Milgram notes in her essay, “Only Ayn Rand could have written the story of Kira, Leo, and Andrei as exemplifying the individual versus the masses.” (8) Part 1 sets up the dramatic Part 2 by depicting the travails of daily life in Soviet Russia, the endless lineups for basic foodstuffs, the kowtowing expected to be given to the Communist Party and its functionaries, the rank opportunism that brings the worst in society to the top. There is the attempted escape by boat to the West and other dramatic moments, but much of the focus is on trying to cope with an inhuman system.

Part 2 is where the drama gets hot and heavy and where some of the best philosophical discussions lie. Often some of the secondary characters, such as Glieb Lavrov, have some of the most powerful lines.

Lavrov is Victor Dunaev’s father-in-law. Dunaev marries a good proletarian girl as part of his attempt to ingratiate himself with the communists. He introduces the elder Lavrov at the wedding reception:

Let us drink our first toast to one of the first fighters for the triumph of the Worker-Peasant Soviets, my beloved father-in-law, Glieb Ilyitch Lavrov.

Lavrov rises.

He said slowly, firmly, evenly:

Listen here, you young whelps. I spent four years in Siberia. I spent them because I saw the people starving and lousy and crushed under a boot, and I asked for freedom. I still see the people starved and lousy and crushed under a boot. Only the boot’s red. I didn’t go to Siberia to fight for a crazed, power-drunk, bloodthirsty gang that strangles the people as they’ve never been strangled before, that knows less of freedom than any Czar ever did! Go ahead and drink all you want, drink till you drown the last rag of conscience in your fool brains, drink to anything you wish. But when you drink to the Soviets, don’t drink to me! (356-357, [290-291 in Signet edition])

In the 1959 edition “I saw the people starving and lousy and crushed under a boot” was changed to “I saw the people starved and ragged and crushed under a boot.”

The irony of a freedom fighter against the Czar recognizing that the Reds are no different, and in fact, often worse, is not lost on the reader, nor on the Communist functionaries and toadies like Victor Dunaev. He immediately hisses at his bride:

In the roar of the crowd, Victor grasped Marisha’s wrist, his nails sinking into her skin, and whispered, his white lips at her ear: “You damn fool. Why didn’t you tell me about him?” (357)

The only one who laughs at the incident is Andrei Taganov, more worldly wise than the rest, and able to see through the veneer of cynicism of his party comrades.

In For the New Intellectual, Ayn Rand used one quote from the book, Kira’s speech to Andrei after he discovers the truth about her relationship with Leo. But she could well have included the elder Lavrov’s short speech. And she could have included Stepan Timoshenko’s speech to Karp Morozov. Timoshenko, like Taganov, is a dedicated Communist who takes his values seriously and is appalled by the corruption and cynical opportunism he sees around him. He encounters Morozov in a restaurant. He knows Morozov is a black marketeer in cahoots with the opportunistic party comrade Pavel Syerov. Morozov and Syerov engage Leo as their frontman and eventual patsy.

In For the New Intellectual, Ayn Rand used one quote from the book, Kira’s speech to Andrei after he discovers the truth about her relationship with Leo. But she could well have included the elder Lavrov’s short speech. And she could have included Stepan Timoshenko’s speech to Karp Morozov. Timoshenko, like Taganov, is a dedicated Communist who takes his values seriously and is appalled by the corruption and cynical opportunism he sees around him. He encounters Morozov in a restaurant. He knows Morozov is a black marketeer in cahoots with the opportunistic party comrade Pavel Syerov. Morozov and Syerov engage Leo as their frontman and eventual patsy.

Timoshenko sneeringly raises a glass of champagne “To the great Citizen Morozov, the man who beat the revolution!” (439, [355 in Signet edition]) The conversation goes on with Timoshenko, drunk and dripping with sarcasm, elaborating on Morozov’s victory over red loyalists like himself. Morozov protests but is steamrollered by the relentless Timoshenko who brushes him aside and continues with his sarcastic tirade. “I’m nothing but a beaten wretch, beaten by you, Comrade Morozov….You’ve taken the greatest revolution the world has ever seen and patched the seat of your pants with it! ….We know that the revolution—it was made for you, Comrade Morozov, and hats off to you!” (439-440)

Timoshenko elaborates on the ruthlessness and bloodiness of the revolution in gruesome detail, which Rand toned down drastically in the 1959 edition. As Mayhew puts it, “Timoshenko is pretty vulgar for a mixed or semi-heroic Ayn Rand character; but this passage goes too far—there’s a sadistic side to it that in the end she did not want to attribute to Timoshenko.” (223)

Personally, I think the gruesome details have a powerful impact. They add a certain emphasis to what he says next. Timoshenko continues:

That’s what we did in the year 1917. Now I’ll tell you what we did it for. We did it so that the Citizen Morozov could get up in the morning and scratch his belly, because the mattress wasn’t soft enough and it made his navel itch. We did it so he could ride in a big limousine with a down pillow on the seat and a little glass tube for flowers by the window—lilies of the valley, you know. So that he could drink cognac in a place like this, and belch, and the waiter would say, “Yes, sir.” So that he could scramble up, on holidays, to a stand all draped in red bows and make a speech about the proletariat…

I don’t mind that we’re beaten. I don’t mind that we’ve taken the greatest of crimes on our shoulders and then let it all slip through our fingers. I wouldn’t mind it if we had been beaten by a tall warrior in a steel helmet, a human dragon spitting fire. But we’ve been beaten by a louse. By a big, fat, slow, blond louse. Ever seen lice? The blond ones are the fattest… It was our own fault. Once men were ruled with a god’s thunder. Then they were ruled with a sword. Now they’re ruled with a Primus. Once they were held by reverence. Then they were held by fear. Now they’re held by their stomach. Men have worn chains on their necks, and on their wrists, and on their ankles. Now they’re enchained by their rectums. Only you don’t hold heroes by their rectums. It’s our own fault. (441)

Timoshenko continues in this vein, lacing his words with sarcasm and anger. Morozov tries to leave:

“Sit down!” roared Timoshenko. “Sit down or I’ll shoot you like a mongrel. I still carry a gun, you know. Here…” He poured and a pale golden trickle ran down the table cloth to the floor. “Drink to the men who took a sacred red standard and wiped their feet on it.” (443, [358 in the Signet edition])

Rand greatly improved the last line by changing it to “Drink to the men who took a red banner and wiped their ass with it!” in the 1959 edition.

There are other little gems throughout the novel but let me close on a personal note. When I first read it in 1973 and now on rereading it, I still don’t really get Leo Kovalensky or why Kira loved him so much. True, their relationship at first seems on solid ground. She is Leo’s rock and pulls him out of his cynicism and despair. He reciprocates and treats her lovingly. They plot and attempt an escape to the West together.

When the escape attempt fails and he and Kira are discovered, he tells the people arresting them that he kidnapped Kira and she is blameless. He willingly offers to sacrifice himself for her despite her protests. In the end they are both released.

After he comes back from his recuperation in the Crimea, he enters into an illegal and risky scheme with Morozov and Syerov in order to get rich and give Kira a taste of what he thinks she deserves, not the destitution and misery they are then living in. Although Kira sees the danger and begs him not to enter this scheme, he replies:

Nothing you can say will change things. It’s a filthy, low, disgraceful business? Certainly. But who forced me into it? Do you think I’ll spend the rest of my life crawling, begging for a job, starving, dying slowly? I’ve been back two weeks. Have I found work? Have I found a promise of work? So, they shoot food speculators? Why don’t they give us a chance at something else? You don’t want me to risk my life? And what is my life? I have no career. I have no future. I couldn’t do what Victor Dunaev is doing if I were boiled in a furnace! I’m not risking much when I risk my life. (333, [271 in Signet edition])

In his essay The Plight of Leo Kovalensky in the Mayhew volume, Onkar Ghate draws a sympathetic portrait of the man, noting all of the above, arguing that Leo is a victim of circumstances, of the unbearable horror of the Soviet system. Nevertheless, he notes that “Leo’s plight and disintegration are difficult to understand.” (316) “There is a growing resentment of Kira, the only one around him who can see and kindle within him the vision of an exalted state of being—which makes life in Soviet Russia unbearable.” (323) As the story progresses, the way he treats her at times is abysmal.

And while he is a Communist, Andrei shines through as a noble, albeit misguided man. His love for Kira is powerful and all-consuming. He bends over backwards to show his devotion to her. And even when he discovers the truth, that she merely used him to help Leo, and never truly loved him, his love remains steadfast. Her happiness means more to him than his own. He conceives and enacts a plan to release Leo, his rival who he had earlier arrested, for Kira’s sake.

Right after the airtight passage quoted above, when Kira confronts him and berates him and tells him he meant nothing to her, she screams at him, “Why do you stand there? Why don’t you speak? Have you nothing to say?” (481)

Earlier in the novel, after Leo returns from the sanitarium in the Crimea, Kira keeps up the pretense of being Andrei’s mistress but makes excuses to see him less frequently. On one occasion when she does see him, Andrei tells her she is “worth all the torture, all the waiting.” (393) He is deeply troubled and she asks: “What’s the matter. Andrei?” “My Party,” he replies. He’s come to see that she was right on things they had discussed:

We were to raise men to our own level. But they don’t rise, the men we’re ruling, they don’t grow, they’re shrinking. They’re shrinking to a level no human creatures ever reached. And we’re sliding slowly down into their ranks. We’re crumbling, like a wall, one by one. Kira, I’ve never been afraid. I’m afraid, now. (394)

He tells her she is the only one who is helping him carry on. “Because no matter what human wreckage I have to see, I still have you. Kira, the highest thing in a man is not his god. It’s that in him which knows the reverence due a god. And you, Kira, are my highest reverence.” (395)

Now she is asking him why he is silent. Why he is saying nothing. “Do you know what it meant when you reached for my highest reverence…” (482) she starts. And then it hits her.

She stopped short. She gasped, a choked little sound, as if he had slapped her. She slammed the back of her hand to her open mouth. She stood in dead silence, her eyes staring at something she had seen suddenly, clearly, fully for the first time.

He smiled, very slowly, very gently. He stretched out his hands, palms up, shrugging sadly an explanation she did not need.

She moaned: “Oh, Andrei!”

He said slowly: “Kira, had I been in your place, I would have done the same—for the person I loved—for you.”

She moaned, her hand at her mouth: “Oh, Andrei, Andrei, what have I done to you.” (482)

The profoundness of the change that has come into Andrei’s thinking, into his view of life, is revealed shortly when they part and he goes to give a scheduled speech at a party function.

… and you’ve locked us airtight, airtight till the blood vessels of our spirits burst! You’ve taken upon your shoulders a burden such as no shoulders in history have ever carried! You have a right to do it, if your aim justifies it. But your aim, comrades? Your aim? (484)

This is the climax of the book. Andrei has come full circle. He has become Kira. He fully and completely knows her, knows her thoughts, understands her in a way only a man deeply in love can.

The denouement begins. All the loose ends are tied up and resolved.

When I started this essay, I thought that Andrei could be compared to Javert, the relentless policeman in Les Miserables who has an epiphany when he has to decide whether to let Jean Valjean go or to arrest him. But on reflection it hit me that Andrei is more like Sidney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities, also a man deeply in love with a woman who does not love him. And like Carton, he rescues the man she loves, giving his life for her sake.

Andrei is a character whose eyes are opened, who grows and discovers his true self, discovers his true values. Leo, sadly, is a character whose eyes are closed, whose love for Kira disintegrates. He squanders what he has.

Kira is caught between the two. She has seen Andrei as an intellectual sparring partner, but also as a kindred soul. But it is only after she has categorically rejected him that she has her epiphany and realizes that she was not a fling to Andrei, that she was literally his soulmate. That he truly and deeply loved her.

To me, Andrei has always been the unsung hero of We the Living. He is the honest idealist with false ideals who learns to see the truth. Like Javert, his past and his present clash in a way that leaves no way out. His ideals have been shown to be a fraud, the woman he loves is unattainable. There is nothing left to live for.

Kira, of course, is the heroine and prime mover of the story. While I find her continued devotion to Leo inexplicable, to her it is a gut reaction. And it is a necessary element of the plot. Rand chose to make Leo a complex figure without the strength of conviction to attain his values. Ghate portrays him as a sympathetic character. He argues that Leo is superior to Andrei because he had the right values at the beginning but they shrivel and die in the morass of the Communist hellhole they find themselves in.

Andrei embraced an evil ideology at the beginning, and, Ghate argues, that makes him the lesser of the two. I disagree.

Andrei embraced an evil ideology at the beginning, and, Ghate argues, that makes him the lesser of the two. I disagree. To grow and change on the discovery of erroneous thinking, especially deeply held but erroneous personal values, displays a quality of character I consider heroic. To give up in resignation and to take out your frustration on the woman you loved is despicable. And I use the past tense here because it is clear to me that Leo no longer loves Kira by the end of the novel.

Kira, of course, is the rock that stands steadfast through all the trials and tribulations. The rock that keeps her soul intact.

Ghate brilliantly characterizes the difference between Kira’s and Leo’s way of thinking. Kira’s approach to life is metaphysical. She sees things in terms of fundamental values, everlasting truths about the individual soul. She has a spirit that can’t be broken, and even when she is fatally wounded, she carries on. “You’re a good soldier, Kira Argounova, you’re a good soldier and now’s the time to prove it… Now… Just one effort… One last effort…” (549, [443 in the Signet edition]) she whispers to herself.

Leo on the other hand, focuses on the concrete present. He is not able to think long range like Kira. And so, his soul is destroyed by the circumstances he finds himself in.

Part of the reason I admire Andrei is, perhaps, because he also takes a metaphysical view. His life centers on his fundamental values. One of those values is a genuine concern for people and for truth. As noted in an earlier quote, he wanted “to raise men to our own level.” His aim was not to tear down but to build up. And when he discovers his methods and ideology do the exact opposite, he changes. He remains metaphysical but his worldview, his values, change. His values don’t shrivel up and die like Leo’s. They are transformed. And that makes all the difference in the world to my view of the two.

In any event, We the Living is a great book, a masterpiece. It captures the hellishness of communism like no other work I have read. And it is not the midnight knocks, the firing squads and the gulags that make it hellish. It is the sheer drudgery of life under this system that makes it hellish. The endless queues, the kowtowing to officious apparatchiks, the crowded and cramped living spaces, the destruction of ambition and achievement—these are the real horror of collectivism.

On a final note, I am curious if anyone else has come across an edition of We the Living as late as 1953. Or later.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Editors’ Comments:

Most objectivists regard We the Living as the lesser of Rand’s long epics, and some even think of it as “naturalistic and nihilistic.” Rand defended the theme as being consonant with no hero can survive communism as a hero, or, if their spirit survives, then their body doesn’t. However, what if the narrative dedicated to showing the drudgery reduced a fair bit? And, more crucially, what if Andrei joined Kira toward a successful escape over the border?

Here’s an alternate ending:

Andrei follows Kira to the border, but in uniform, and at a distance, and in a jeep. He then pretends to be searching for her while leading the search party astray. Nevertheless, as Kira gets very close to the border, she is shot in the leg from a distance, but she’s hidden amongst trees.

When they hear the shot half a mile away, Andrei instructs the other soldiers to stay put while he drives toward Kira. As the soldier who shoots her gets really close and is about to put a bullet into Kira’s head, Andrei shoots and kills him. He then lifts the injured Kira into his jeep and then they get over the border. THE END.

Would that, in your opinion, dear reader make for a much better reading experience or a worse one?

—Vinay Kolhatkar

The counter opinion

Kira and Leo represent the West. The very first things that we learn are that Kira dreams of the West—and that this man calls himself “Leo” rather than “Lev.” And it is because he shares Kira’s longing for the West. The last remnant of any Western influence is perishing in Russia. Before the Bolshevik revolution, there was a powerful, long-standing current of Western culture among Russia’s liberals going back to Peter the Great. That trend, powerful for so long, was obliterated by the Bolshevik revolution. I think that Leo symbolizes that. In the end, if Kira cannot save him, she must die trying to reach the West. That Andrei becomes philosophically awakened is not about love. Love is about sense of life. And Leo and Kira share the Western sense of life. Kira cannot keep it from dying in Russia. The only chance is to try to get to the West.

The West for Kira is a sense of life, “The Sound of Broken Glass,” and that is what Leo means to her. But that sense of life has no place in this Russia. Kira gives everything to keep it alive. She is the indomitable exemplar. But she fails to sustain it. It cannot breathe in Bolshevik Russia. It can only try to escape. Or die trying. It is all about sense of life, I think.

—Walter Donway